Doug Kenney was one of a few people who re-created comedy at the end of the 1960s. Joke writing had, a decade earlier, begun to move beyond its vaudeville-and–Borscht Belt past into the Mort Sahl–Lenny Bruce era, and now it was time to take it into the counterculture future. Kenney’s credits make it clear that he was one of the people who did that: co-founder of National Lampoon magazine, writer of (and one-line actor in) Animal House, writer-producer of Caddyshack. You can see a version of his life story in Netflix’s A Futile and Stupid Gesture, a biopic based on the book by Josh Karp. But the film plays with the timeline and the facts — its very framing device, which I won’t spoil here, makes that explicit — and viewers who were not around for the 1970s heyday of the Lampoon may not quite recognize all the visual references and characters, apart from the people who got famous later on Saturday Night Live. It’s time for a primer.

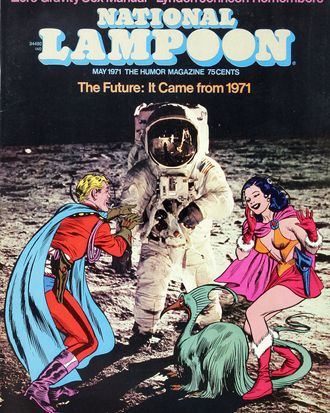

The National Lampoon itself was, as the movie establishes, created with the idea of taking the ethos of the Harvard Lampoon off campus and onto newsstands. What was most significant about the magazine, when it appeared in 1970, was the deadpan intensity of its humor. There was, on most of its better pages, a joke or a headline or an image that could make you gasp and suck in your breath as you laughed (and laughed hard). It was not for everyone, god knows: It was too mean and too dirty for a lot of people. But if you were hip enough to get it, it was taboo-breaking in the best possible ways. When it was good, it was astounding. And, to be fair, it also found a certain amount of its humor in racist stereotypes and language, and although sometimes that racism was deployed ironically, it does not always come off that way. That was equally true of the relentless sexism in its pages. And in its offices: The managing editor, Mary Martello, was nicknamed Mary Marshmallow because of her curvy figure. In fact, there were a lot of jokes about breasts in and around the National Lampoon.

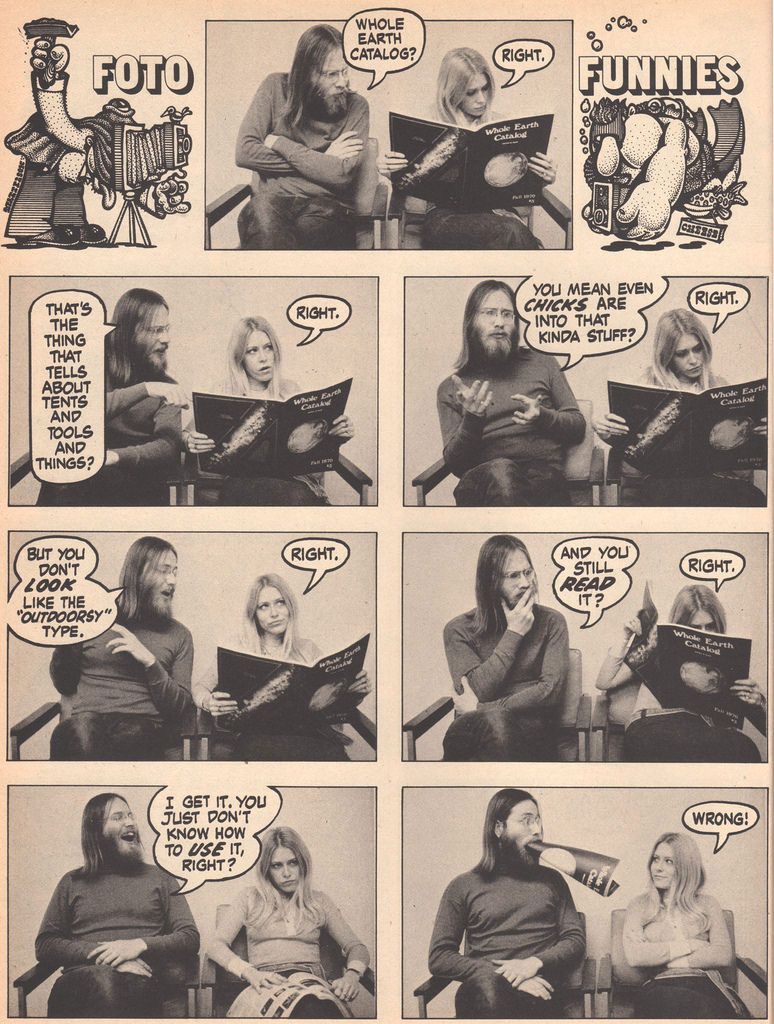

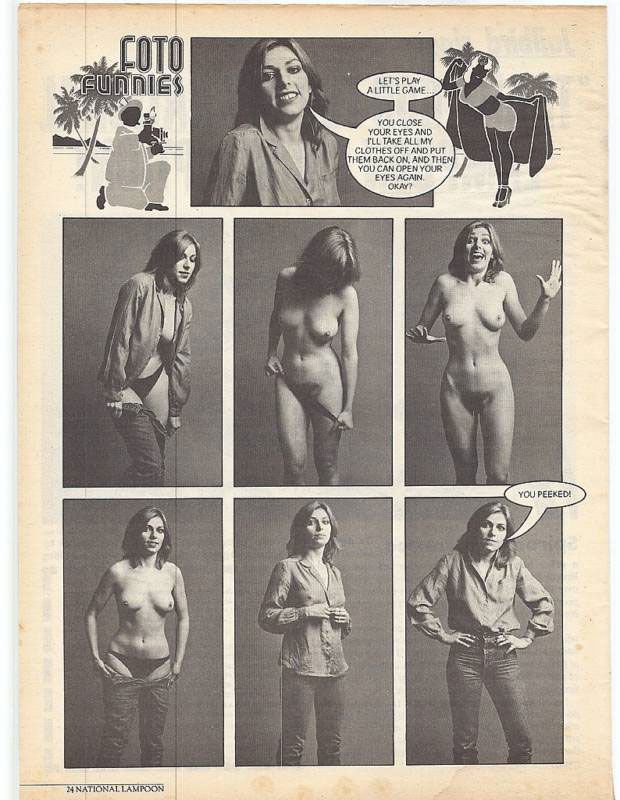

Which brings us to Foto Funnies, the magazine’s monthly comic strip. It was a one-page example of fumetti, using photographs with added speech balloons instead of drawings. (A “Foto Funnies” treatment is used as a narrative device in the film A Futile and Stupid Gesture.) Kenney himself created the series, and appeared as a model in a bunch of them, as did other contributors at various times. So did “Danielle,” a three-time winner of the Miss New York City Big Breasts Contest. Needless to say, she was topless, and sometimes bottomless, in the photos, as were a lot of the other women who posed. It was not the greatest feature in the magazine, but it was pretty popular anyway, for reasons you can probably figure out.

Danielle had been brought to the editors’ attention by Michael O’Donoghue, one of the magazine’s first writers. You may know him from his later writer-performer role on Saturday Night Live, where he spoke the first line in the show’s first sketch in October 1975. Before SNL, though, he was the anarchist of the National Lampoon’s staff, and “dark” does not begin to describe his interests or his comic voice: jokes about genocide, terrorism, and serial killers were his staples. He was responsible for “The Vietnamese Baby Book,” arguably the story that set the Lampoon’s early “there’s no line we don’t cross” tone. (It was an extended napalmed-infant joke.) O’Donoghue was notable for his unhinged, terrifying temper tantrums, one of which appears in the film — it’s surely less scary onscreen than in life — and over the years he broke with or alienated many of his colleagues by the time he died from an unexpected stroke in 1994, at the age of 54. There’s a great biography of him called Mr. Mike, by Dennis Perrin.

At one point he lived with Anne Beatts, one of the few female voices on the magazine. In that openly misogynistic environment, she gave as good as she got, and outwrote a lot of her male colleagues at the magazine and thereafter. (She once described the environment as akin to a voter-suppression test: “Everyone else had to spell ‘cat,’ and you had to say when the Edict of Nantes was revoked.”) The 1976 anthology of women’s humor that she edited, Titters, is wide-ranging and intellectually democratic (Gilda Radner’s in there, but so is Erma Bombeck) and is today regarded as something of a feminist landmark. Beatts, like O’Donoghue, went on to write for SNL, and later created the beloved comedy series Square Pegs, which turned the world on to Sarah Jessica Parker.

She and a number of Lampoon colleagues co-wrote Lemmings, a stage show spun off from the magazine that appeared in New York in 1973. It was the proto-SNL in many ways: Chevy Chase and John Belushi were in the cast, and Christopher Guest co-wrote and performed the music. Belushi’s Joe Cocker impression that was such a success on TV had been developed onstage. The Lemmings cast album sold well, and is probably the best way to experience the show today — at least until the revival, reportedly in the works and produced by Lorne Michaels, comes to the New York stage in 2019.

The original producer of Lemmings was Tony Hendra, the British Lampoon contributor who is played in the film as a bit of a buffoon. Hendra himself, though, is far more recognizable from his later role playing Ian Faith, the manager of the band in This Is Spinal Tap. He also became the editor of Spy (admittedly not its best era) and a wine critic for New York. In 2004, he published a confessional memoir in which he discussed being an absent and disengaged father — which was promptly followed by his daughter’s public and credible accusations that he was not only a lousy parent but had molested her.

If there’s a central figure in the film besides Doug Kenney, it’s his Harvard classmate and National Lampoon co-founder Henry Beard. In real life, Beard is an enigmatic, laconic figure: He spent five years editing the most interestingly vicious humor magazine ever to hit newsstands, in the role of house grown-up. After he and Kenney took a buyout, Beard pretty nearly disappeared for a few years. Since then, he has written three dozen funny if not especially ambitious books like Sailing, a joke dictionary of yachting terms; Latin for All Occasions, with translations of phrases like “Run into much traffic on the way over?” and “In a world of hurt”; and Poetry for Cats. They sold (and sell) like crazy, and he’s reportedly made millions of dollars therefrom. He has tended to avoid speaking about his time at the National Lampoon, though he has occasionally offered a little about it in interviews like this.

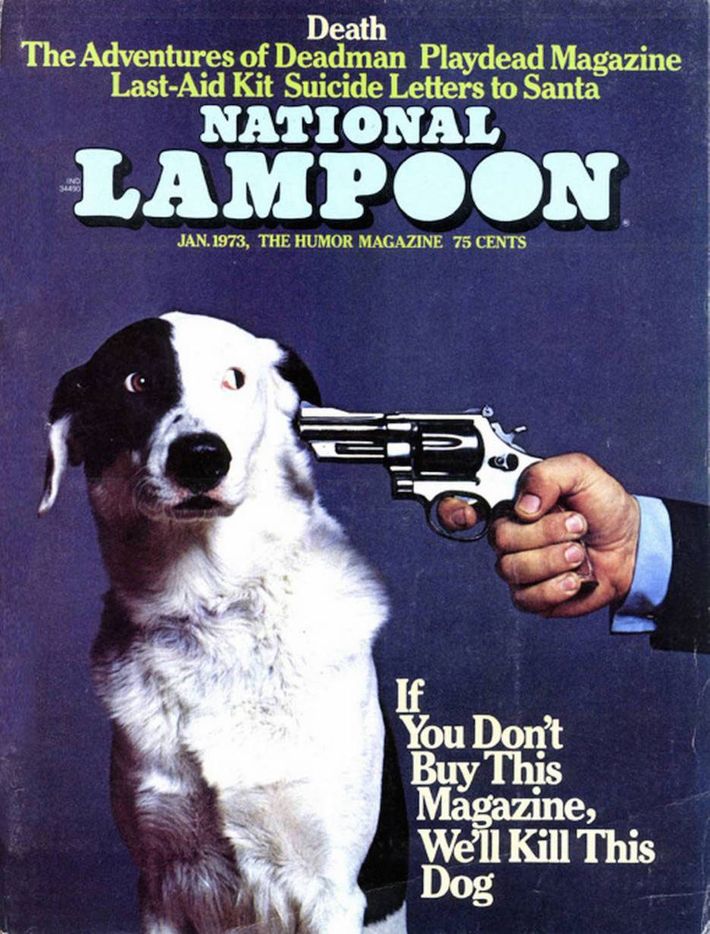

Every magazine has a definitive cover, and the National Lampoon’s best and most famous one goes by quickly in the film. The headline came from a writer named Ed Bluestone, and it was “If You Don’t Buy This Magazine, We’ll Kill This Dog.” The photograph shows a sweet-looking canine with a gun to his head. It’s a piece of National Lampoon lore that, at the photo shoot, the image didn’t quite come together at first, because the dog wouldn’t look at the gun. The secret, it turned out, was that the hand model holding the pistol had to pull the trigger. The dog heard the click, flicked its eyes, and created an image for the ages.

But the thing for which the Lampoon is likely to be most widely remembered is not the magazine. That would be Animal House, the film that reinvented screen comedy and broke box-office records upon its release in 1978. Much about it still feels current: the Ivy League sensibility that to this day filters into almost every sitcom; the big cast of young, not-very-well-known stars; and the vague hints, evident in (for example) Judd Apatow’s films, that the cast and creative team are mostly friends.

The Lampoon itself lasted past the Beard-and-Kenney era, but it stumbled (both financially and editorially) in the 1980s, and after sputtering on for a few years printed its last issue in 1998. The movies have kept on, with varying degrees of success — the Vacation series was of course wildly successful, and the last one that really performed was the campus comedy National Lampoon’s Van Wilder, in 2002 — but most of them are direct-to-video duds. Last year, the brand was purchased for a mere $12 million by a company called PalmStar Media, which hopes to rejuvenate it, or at least license the old name and material. They bought the magazine; now they have to keep the dog alive.