Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible.

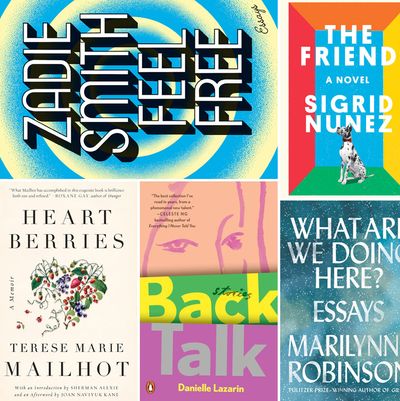

Feel Free, by Zadie Smith (Penguin Press, Feb. 6)

Smith is as famous for what she thinks as what she makes up. In this new collection of essays her subjects range from highbrow to low- (Knausgaard to Bieber), from politics (Brexit) to tech (Facebook), and from the arcane (Schopenhauer) to the personal (her father). Feel Free is a shepherd’s pie of nonfiction whose only through line is a writer unafraid of getting lost, because she always knows the way home. Smith has mixed it up with critics since she herself was a wunderkind with a giant advance, but age hasn’t hardened her against the world, only made her more porous.

An American Marriage, by Tayari Jones (Algonquin, Feb. 6)

It’s nice to have Oprah on your side, but the latest book-club pick of the president-in-waiting has long been tipped as the most relevant novel of the winter. It’s also, more importantly, a propulsive story deftly told. Celestial and Roy are barely married when Roy is wrongly imprisoned for rape, and while their love simmers in letters, she begins to fall into the romantic orbit of her friend André. The love triangle unfolds in alternating narratives, driven by the plot device of racial injustice but made flesh by a passionate writer.

Back Talk, by Danielle Lazarin (Penguin, Feb. 6)

At a critical moment in feminist history, Lazarin’s intimate stories find women of almost all ages exploring the essence of freedom and the mixed blessing of human entanglement. In one piece a woman toys with picking up a stranger as she mourns a recent breakup; in another, a traveler chronicles the pickup artists she rejects in favor of a long-distance romance. There’s a tale of nascent friendship complicated by real estate, and then there are stories of teens coping with death, pain, and the consequences of pleasure.

Asymmetry, by Lisa Halliday (Simon & Schuster, Feb. 6)

Come, if you must, for the roman à clef tucked into this novel by an author who had an affair with Philip Roth 20 years ago. But stay for a story composed ingeniously out of three disparate parts. In the first, Alice loves the much older Ezra as the Iraq War rages in the background; in the second, an Iraqi-American is trapped in Heathrow’s Kafkaeque passport control. In an epilogue, Ezra muses on love and inspiration for an episode of BBC’s “Desert Island Discs,” providing the plot hinge of a story about — what else? — the transformation of life into fiction.

The Friend, by Sigrid Nunez (Riverhead, Feb. 6)

A serious book about a big sloppy dog, Nunez’s seventh novel — and her first book since Sempre Susan, about Susan Sontag — displays the intellectual heft of her late friend’s work, but also a distinctive sense of humor and narrative momentum. The unnamed narrator, a writing professor inhabiting a 500-square-foot apartment where pets are forbidden, inherits a Great Dane from a friend, a writer of Rothian sexual appetites, who recently committed suicide. Her meditations in his wake brim with literary references and bittersweet laments for a better-read, less polarized world.

Heart Berries, by Terese Marie Mailhot (Counterpoint, Feb. 6)

There is plenty of misery in Mailhot’s memoir, but also something fresh: a sort of lived-in, jargon-free intersectionality. Mailhot grew up on a reservation in British Columbia, and Canada’s shameful legacy of marginalization undeniably fueled the abuse that raged through her household, ultimately causing or intensifying the mental breakdown that caused her to commit herself to an institution. Mailhot wrote her way out of that madness. The incidents she recounts are horrific on their face, but rendered with a sense of proportion and self-knowledge that rarely emerges from happier lives.

What are We Doing Here?, by Marilynne Robinson (FSG, Feb. 20)

If Zadie Smith’s essays are snapshots of the writer in the here and now, those written by Robinson, a laureled septuagenarian novelist who revels in her own “unhipness,” seem eternal. Which is not to say that her arguments aren’t contemporary: Robinson describes Obama, who interviewed her at length, as the best we could have hoped for in a modern president. She also published the title essay, defending the common-sense virtues of the humanities, on the day after we sort-of elected the would-be annihilator of those virtues. Now more than ever and forever after, we need Robinson’s fiction and her truth.