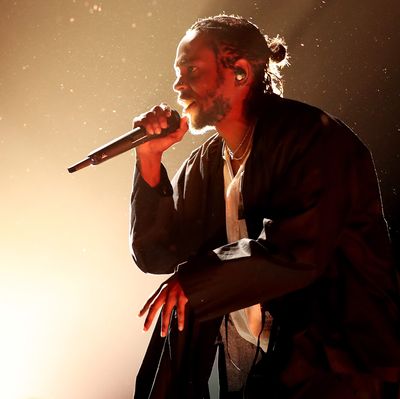

If it’s not quite redundant to say that the soundtrack for Black Panther is, well, a soundtrack, blame Kendrick Lamar. His audience has grown accustomed to the Compton superstar traversing five dimensions in each individual album; it’s easy to imagine that the Panther soundtrack, curated and produced by Lamar and featuring him on every track, is operating along similar polyvalent lines. Like his proper collections, Black Panther: The Album is a stage for political statements channeled through religious callings and personal commitments. “It’s all prophecy, and if I gotta die for the greater good then that’s what it gotta be,” Lamar spits on closer “Pray for Me.”

But the collection is also, to a unique degree, an opportunity for dispensing patronage and building alliances. On many tracks, Lamar’s vocals peek in like a gifted party host, introducing disparate sounds and artists to each other and supplying them with an occasion to converse before tastefully fading away. SZA and Kendrick’s Black Hippy teammates Ab-Soul, Jay Rock, and Schoolboy Q all get a prime slot to flaunt their powers of language. “Pray for Me” affirms a prior partnership with the Weeknd; other tracks do the same with Travis Scott and Future. Lesser-known artists from SoCal to South Africa to Sacramento have a chance to deliver star turns, and do so; delegations from Atlanta and London are honorably received. It’s a chance for Kendrick to be the circumference instead of the center of the world: Imagine Graceland fused with Wakanda and distilled into a playlist. Lamar’s sense of perfect timing and competition manifest more indirectly: BP:TA’s 49-minute length compares favorably to Drake’s own African-inflected playlist More Life, which, though not a soundtrack, is as long as a feature film.

“Opps” is the track that sums up his vision for the whole collection. Consciously or not, Vince Staples has been operating as a kind of understudy to Kendrick. Like Kendrick, he is, at 24, a precocious, critically acclaimed, and politically astute talent. Kendrick’s pairing of Staples with Ludwig Göransson’s racing Afro-EDM beat shows a keen awareness of Staples’s current instrumental comfort zone, and Staples slices through the hurtling digital sonics with a delivery exuding, as always, next-level cool under extreme pressure.

It seems improbable that Vince’s poker-faced precision and Kendrick’s calibrated bursts of arrogance could be upstaged, but that’s exactly what happens once South African rapper Yugen Blakrok arrives: Rich with colorful metaphors and varying in flow, her 24-bar third verse immediately eclipses her more famous partners.

I’m half-machine, obscene with the light sword;

Look inside the brain, it’s a ride in the psych ward.

What you standing on the side for?

Roar like a lioness, punch like a cyborg.

Spit slick, my attack is subliminal:

Flowers on my mind, but my rhyme style sinister;

Stand behind my own bars like a seasoned criminal.

In less than 45 seconds, South Africa is back on the hip-hop atlas in a big way. But where A Tribe Called Quest or Dr. Dre referenced the struggle against apartheid in the ’90s, now South Africa itself, liberated, has given rise to a rapper who can match the highest standards of the genre. The prospect of black self-determination is a theme strong enough to link fictional Wakanda with the real red Compton, blue Long Beach, and rainbow-flag Johannesburg. If reality often falls short of the moving image, that hardly subtracts from its power when, accompanied by thrilling music, the execution proves so masterful.