“By the way, did you see the video of Trump’s hair in the wind?”

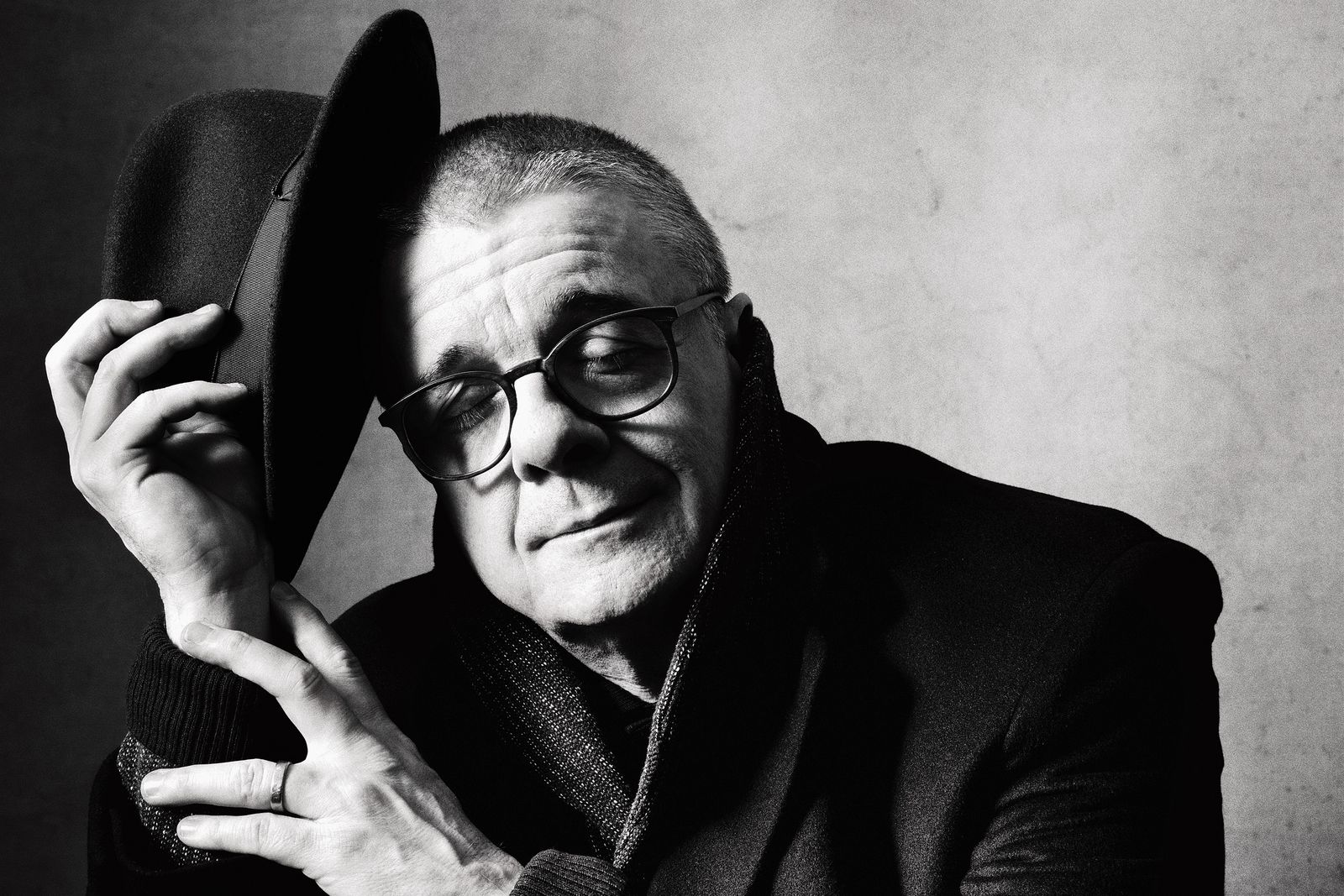

In acting training, teachers refer to a performer’s body and voice as an instrument, but in the case of Nathan Lane, what you’re really dealing with is an orchestra-type situation. Even seated at a restaurant table, preparing to explain a crisis he faced in his career eight years ago, he uses the full melodic range of his voice and places the emphasis just so. His mind works very fast; often a sentence comes punctuated with a tiny chuckle halfway through, because, while he’s talking, he’s also formulated a punch line that he knows will kill.

Thus Nathan Lane’s exegesis of Trump’s hair in the wind:

“It’s as if Mother Nature herself — or, if you believe in God, God — had a hand in this. As Trump’s walking up, the wind is fiercely blowing” — and here his hands become the wind over the tablecloth before shooting out to emphasize Trump’s hair — “this Frankenstein concoction of Just for Men hair spray and Zero Mostel hairstyling! It blows it all away, this façade of hair, and it’s revealed that there’s absolutely nothing there. I couldn’t think of a more perfect metaphor for what’s happening than that.”

Nathan Lane does nothing halfway, whether it’s in a restaurant or the rehearsal hall. As his frequent director and longtime friend Joe Mantello tells me, “From the moment you open a script to do that first read-through, Nathan’s giving you 100 percent. He’s out in front of the pack, setting the pace, setting the energy, setting the level of commitment, so that everyone else in the room has to rise to that. To me, there’s nothing more thrilling.”

In 2010, when he embarked on the self-reinvention that has led to playing the monstrous, magnetic real-life Republican fixer Roy Cohn in Angels in America, Lane didn’t do that halfway either. During Lane’s year-and-a-half-long turn as Gomez in the critically reviled Addams Family musical, Charles Isherwood, then a New York Times critic, wrote a glowing essay about his abundant gifts. “Isherwood wrote a really lovely tribute to me, about my work, and referred to me as the last of the great entertainers,” he says. “It was all very flattering, and I was very touched by that, but I can find the dark cloud in any silver lining!”

The dark cloud was that pesky word entertainer. Sure, he’d played Nathan Detroit in Guys and Dolls and Pseudolus in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. He’d been Terrence McNally’s muse for the best period of his writing career and had found success in movies and TV. And yet. “Many people just saw me as the guy who was in The Birdcage,” he says, “or the guy who was in The Producers, or, if you’re a Russian cabdriver, Mouse Hunt.” He recalled a conversation from many years earlier with Kenneth Branagh. “We were talking about certain parts, and he said, ‘You can’t just talk about these parts — you have to do them. There’ll be people who carp and ask why a comic actor is playing this part. Whatever. Who gives a shit? It will be life-changing, because these are the parts that test you, and you’ll never find out until you try them on.’”

So that’s what he did. He happened to read that Brian Dennehy and director Robert Falls were thinking about staging Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh but hadn’t yet found their Hickey, the traveling salesman who returns to Harry Hope’s Saloon to try to wrest its denizens from the delusions that shape their lives. Hickey’s five-hour journey from razzle-dazzler to broken man begging to be executed is one of the great mountain-climbing challenges of the American theater. “I thought if I walk in, the audience feels the same way that the guys in the bar do about Hickey. It’s like, Oh, this guy’s just here to show us a good time, and then he doesn’t,” Lane says. “We pull the rug out from under you.”

As Falls tells it, “I got an email from Nathan saying he was sure I was thinking about someone else for the role, but if I’d give it any consideration, he’d be delighted.” Falls was equally delighted. “My first experiences with Nathan as a fan go back to his work as an actor, to the plays of Simon Gray. And seeing him in Terrence McNally’s The Lisbon Traviata — that was a profound moment for me.” The gamble of casting him in The Iceman Cometh paid off, and the show was a huge success and eventually was revived by BAM in 2015. “After Iceman, everything seems easy, and you’ll never be quite the same,” Lane says. “O’Neill is asking you to be as brave as he is in the writing, and things happen to you.

It’s very emotional. It’s the same thing Tony does.”

“Tony,” of course, is Tony Kushner, whose Angels in America announced him as a great American writer, public intellectual, and force of nature 27 years ago. Over the ensuing quarter-century, Kushner has remained Angels in America’s steward, careful about how it is produced and directed and who is cast in it. “I think this is true of every single person who has ever asked me to do the play — I say, ‘You can do it, but first you have to tell me who’s going to play Roy Cohn,’ ” Kushner told me. “Not only is it a star part because it’s this big flashy part, but Roy is a famous person in New York in 1985, ’86. He’s somebody the other characters who are fictional would recognize.” To Kushner, Nathan Lane seemed like “a great idea. He’s the right age. The right temperament. Being a gay actor would be useful. And the fact that he’s one of the funniest people in the world doesn’t hurt. He’s always brought a degree of emotional depth and complexity. He’s not just ‘A little song, a little dance, a little seltzer down your pants.’ ”

Falls offers that “the greatest comic actors are often fueled by difficult childhoods, anger, deep sadness. There’s a well, a reservoir, that I think Nathan draws upon.” Lane’s childhood was indeed difficult, in a specifically O’Neillian way. His father drank himself to death when Lane was 11, and his mother suffered from manic depression. This, combined with Lane’s frankness when he is unhappy, has given him a reputation for using his humor to disguise a more tragic, pained self. In our time together, however, he seemed genuinely happy, prone to self-deprecating jokes about his age (he’s 62) or about how he is worried that “this is the worst interview you’ve ever had to do.” Perhaps it’s that he is romantically settled — he married his longtime partner, Devlin Elliott, in 2015 — or perhaps it’s that, as Mantello puts it, “he’s always seemed happiest to me when he’s undertaking the impossible.” And the latest impossible mountain he’s climbing is named Roy Cohn.

At the time of Cohn’s death in 1986 from AIDS-related complications, he had been a celebrity for 35 years. Known for prosecuting Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and then counseling Senator Joseph McCarthy, and then for his long and vicious career in private practice, Cohn had a knack for courting powerful friends and destroying enemies. That served him excellently as a lawyer for John Gotti and the young Donald Trump. As Lane put it, “Cohn was a really smart guy. And Trump is not a really smart guy. But the main things — never surrender, never admit defeat, even when you lose, declare a victory, counterattack, hit them ten times harder than they ever hit you? I certainly think that was instilled in him by Roy.”

Back when Cohn was tutoring Trump, Nathan Lane moved to New York. He skipped college and learned by doing, working in summer stock and dinner theater while reading voraciously about the stage. “I find that experience has always been the best teacher. Also working with great people. Observing, watching them in action.” He’d see plays whenever possible, second-acting them when he couldn’t afford tickets. “I used to love that — just grab a program someone had dropped and walk in. In those days they weren’t so strict. I saw a lot of great shows that way when I was a starving actor.”

In the beginning, he worked odd jobs, conducting phone surveys and delivering singing telegrams. He sang one to a young Sam Waterston on his birthday and another at an Italian wedding where he wound up being heckled by the band. “You know you’ve hit a new low when accordion players are heckling you! So I started to heckle them back, and then the patrons of the wedding yelled out, ‘Keep talking!’ because I was making them laugh. So I talked. I told them about my sad life as a struggling actor, having to do singing telegrams, and, when I finished, they threw money at me. Like some old vaudeville outfit. That’s eventually why I decided to try my hand at stand-up. I thought there must be something to this.”

He formed a doubles act with the actor Patrick Stack and took it to Los Angeles. Stack stayed out west, and Lane came back to New York in 1982 to co-star in a short-lived sitcom, One of the Boys, with Mickey Rooney, Dana Carvey, and Scatman Crothers. Soon afterward, he made his Broadway debut in Noël Coward’s Present Laughter, directed by and starring George C. Scott. “He was one of my heroes as an actor, but he was a tortured soul and self-destructive,” Lane says. “He was hilarious in it. I remember opening night sitting onstage, and he’s yelling at me, and right behind him I can sort of see Tony Randall, who’s there watching the show, and I’m thinking, Wow! Tony Randall! This is it, baby! I guess I’ve made it! George C. Scott is screaming at me on a Broadway stage, and Tony Randall is watching him do it!”

Present Laughter opened in the very early days of the AIDS crisis, a year after the New York Times ran its first story about it, headlined RARE CANCER SEEN IN 41 HOMOSEXUALS. “I’m lucky to have survived,” he says. “It was a terrifying time. There’s all this research we were doing at [Angels’] rehearsal in London, talking about the ’80s as a period piece. I’m a living artifact. It’s great, I think, for people to be reminded of where we were then. How we’re having the same arguments now, and it’s happening at a time when we’re in a constitutional crisis, democracy itself is at stake. It’s unbelievable, and all because of fucking Roy Cohn.”

To play fucking Roy Cohn, you need to embody a larger-than-life charmer, grandiosely performing while always looking for a chance to go in for the kill. You must summon a man furiously fighting to win a doomed war with death itself; visited by the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg; cared for by Belize, a black, gay ex–drag queen; and disappointed by Joe Pitt, your protégé and possible erotic fixation. You must somehow juggle the three words on the first panel dedicated to Cohn in the AIDS Names Project Quilt: Bully. Coward. Victim.

You need to bring technical mastery and emotional commitment at the same time. You must remain present with the audience and your scene partner, and embody Roy’s will to dominate while also remaining part of an ensemble. It’s not just Roy’s show, after all. Angels has four main characters, and its protagonist is Prior Walter, a gay man with AIDS who may be about to become a prophet, played in this production by Andrew Garfield.

The most startling thing about Lane’s performance as Cohn is the way he uses his technical mastery over his body and voice to chart Cohn’s physical decline step-by-step. It begins with tremors in his hands and grows to a weakening of his voice, until he gasps for breath and can speak only in a parched whisper. By the end of “Perestroika,” the second half of Angels in America, his body is convulsing in full seizures.

“He’s really exploring — in ‘Perestroika’ — what it means to die,” Kushner says. “It’s very shocking, the moment when his voice changes from one act to the next. You just hear his major weapon, his greatest instrument, beginning to fail him. His voice, his ability to talk. And that’s just stunning.”

It isn’t all just technique, however. “People have said to me, ‘It’s very upsetting to watch.’ And I have to admit it, it’s very upsetting to do,” Lane explains. “You have to let this thing happen, and it’s just awful. But I think it’s important to see. It’s awful to watch anybody go through it, even a prick like Roy Cohn. He’s a vile human being, but he’s still a human being, somewhere in there.” Cohn’s dying interview, for 60 Minutes, which Lane watched again and again for research, “is tragic. He could have done something great,” says Lane. “He could have said, ‘I’m gay. Yes, it’s a horrible disease; yes, I have AIDS.’ Often, I go back and look at that video, and I keep thinking, Roy, just say it! Go ahead, tell the truth for once. But he couldn’t. It just wasn’t in him to do that.”

I ask him if, like many others who have assayed Cohn, he struggled with his own hatred for the real-life figure. “Can I tell you something? Just between you and me and New York Magazine?” Nathan Lane leans in and beams, speaking directly into my recorder: “I love being Roy Cohn!”

Now it’s 7 p.m., and, having navigated the Neil Simon Theatre’s labyrinthine backstage, I’m sitting in the house to watch Nathan Lane tech through a scene from the end of “Millennium Approaches,” the first half of Angels. Earlier, he warned me to keep my expectations for the tech rehearsal low: “Tech will tell you nothing. Tech is when the play goes away.” For the past few weeks, the cast has been in a rehearsal hall in Dumbo, “doing really spectacular work in very intimate circumstances. And now, now we’re in this barn of a theater, and we have to figure out the backstage choreography because it’s very different from London.”

Accompanied by Adrian Sutton’s mournful score, an apartment rises onto the stage as if from the depths of hell, and there he is, the devil himself. Cohn is sick, slumped in a chair like his insides have crumpled. He clings to a tumbler of whiskey as if it were the edge of a cliff he’s about to go over. Yet there’s a ferocity in the set of his jaw, a determination to win at all costs. All this is present, visible, right in Nathan Lane’s body, before a line of dialogue has even been said. I didn’t know you could act clamminess, but there you go.

Lee Pace’s Joe Pitt has cheekbones like daggers, and he towers over Lane in a custom-tailored overcoat, yet he is wary. He knows the rage that Cohn can unfurl. To Pace, this scene is one of the most important in Joe’s journey. “By observing the monster Roy has become, it’s a crucial step for Joe’s path toward saying ‘This is not who I am; this is not who I can become.’ ”

But before Joe can get there, he has to start the scene and turn down a job at the Justice Department that Cohn has arranged. “I can’t,” he says. “The answer’s no. I’m sorry.”

Lane nearly throws away Cohn’s response (“Oh, well, apologies”). Even if you don’t know what’s coming — roughly a page of invective in which Cohn calls Joe a “dumb Utah Mormon hick shit” — you know the resignation on his face is simply the tall grass hiding a viper preparing to strike. Despite his ample warnings to me, Lane has shown up to do some work, and his performance is as precise and exacting as it was when I saw it a year before in a sold-out house in London. As Marianne Elliott, the director of this production, puts it, “Even if we’re doing it just to run a few lines, he never does anything less than deliver the emotional truth in that moment.”

For Kushner, “He is one of those very rare great actors who decides that this is where he belongs and what he wants to do. In a way, this is a completely selfish act on my part, because I got to have Nathan Lane play Roy Cohn, but I also felt like this was a little contribution. We all have to take care of each other, and anyone who cares about American theater should care about seeing Nathan play Willy Loman or James Tyrone. He should be doing Falstaff. He should be doing King Lear, because he just has such an ear for complicated language.”

There in fact have been conversations about having Nathan Lane play Willy Loman, in a production co-starring Laurie Metcalf and directed by Joe Mantello.

And he’d like to do more Shakespeare, given the opportunity. Here and now, however, Lane is giving Cohn his all, even though it appears that only four people are paying attention to him: Pace, Elliott, Angels’ publicist, and me. There’s a choreography rehearsal for “Perestroika” in an adjoining room, and soon the sound of voices and laughter is too loud to be ignored.

The scene halts, and Lane looks up and out at the house. “It’s hard to concentrate,” he says softly. Elliott runs onto the stage to give Pace notes while the lighting team makes adjustments. Lane sits quietly. At first I think, Ah, now, I will see Nathan Lane at rest. But no. Sitting in the chair, his eyes scan the house, checking the sight lines. “You look up, and there’s this vast mezzanine that goes on and on to the heavens,” he had told me earlier. “Those people way, way, way up there in the last row? I used to be one of those people, students or whoever.” His job, as he sees it, is in part to figure out how “to reach them and not lose what you had in the rehearsal room.”

The stage manager asks them to take it from Cohn’s line “You’re not dead, boy, you’re a sissy.” Lane nods and then there’s that look I’ve come to recognize. He’s about to tell a joke, and it’s gonna kill. He smiles. “‘You’re not dead, boy, you’re a sissy.’” A pause. “He doesn’t mean it in a mean way.” Everyone laughs, but a moment later, when the scene restarts, the genial good humor has vanished. His upper body sags as if the Earth’s gravity had a special love for him, but the steel is back in his jaw. There’s Roy Cohn again, summoned forth by Nathan Lane, just as devastating — and devastated — as ever.

*This article appears in the February 19, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!