Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible.

So many novels about immigrant families are sprawling and populous but conventionally told. Castillo reverses the polarity in her debut novel about Filipino-Americans in the Bay Area. She renders the intimate stories of a small group — Pol, a well-born surgeon reduced to security work; his alienated wife, Paz; Hero, the scarred ex-revolutionary niece they take in; and the couple’s teen daughter — using methods as adventurous as her battle-worn heroine. Castillo shifts tenses and points of view, sprinkles in native languages, and takes other risks that pay off thanks to her powers of perception.

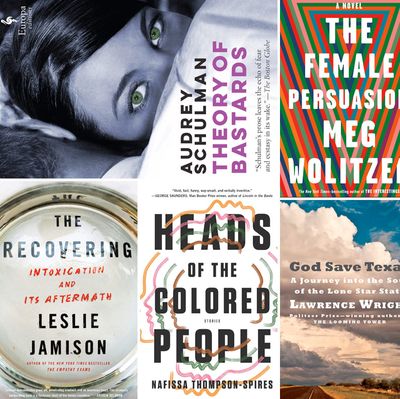

Wolitzer has always written smart and breezy books that also dissect the conundrums of being a woman in the world. Her first novel since the best seller The Interestings charts the generational tensions among feminists just in time for a #MeToo era that deepens those divides. In this juicy fictional “warm take” (to quote the author from a recent interview), a college woman named Greer finds empowerment from an older feminist on campus, only to grow dismayed and confused when the mask of her mentor’s idealism comes off.

By the standards of posterity, personal essays may be the genre with the highest bar; it’s a long way from, say, Candace Bushnell to Nora Ephron. Her third time out, after a break to write the warm and witty novel The Clasp, Crosley seems poised to make the leap. From “Outside Voices,” which packs urban class critique and meditations on time into a rant about an insufferable neighbor, to a painful and cliché-free account of freezing her eggs, Crosley reemerges a wiser — but still often hilarious — observer of city life and human nature.

A latter-day Susan Sontag to Crosley’s Ephron, the author of the genre-changing collection The Empathy Exams takes her blend of the personal, reportorial, and scholarly to expansive new lengths and depths with a discursive examination of addictions (including hers) held together by her preternatural gift for high-concept storytelling. Jamison’s recovery account is far from typical — her rock bottom was higher than many people’s ceilings — but it’s the uniqueness of her case studies, as well as the power of addiction as metaphor, that really make it stand out.

The focus on blackness in this debut collection of stories may be the least interesting thing about it. Or rather, what’s interesting is the use Thompson-Spires makes of race — as a plot driver, irony engine, and comic goad in the manner of Paul Beatty. The most memorable stories, including the title piece about a comic-convention melee and a three-story cycle about two black students in a very white private school, feature African-Americans set against each other by a system that makes room for only a few success stories.

The key to understanding the intentions of Barnes, whose similarly themed novel The Sense of an Ending won a Man Booker Prize, is realizing the title is ironic. Paul’s wry first-person narrative of a doomed long-ago love affair with a much older woman he met at his mother’s tennis club leaves out the stories of others — his sad and unstable lover, her neglected children, and her disdained husband. But Paul isn’t one of literature’s great chauvinist monsters, just an unreliable narrator of the most plausible kind: the narcissist next door.

After worrying about what’s wrong with Kansas, dissecting Ohio election precincts, and marveling over the weirdness of Florida, it might be time for political obsessives to mess with Texas, a state that grows ever more polarized even as it becomes more diverse and, if not quite purple, at least lighter pink. Wright, a lifelong Texan and a Pulitzer Prize–winning author (The Looming Tower, Going Clear), knows his way around the state’s contradictions, from its wild borderlands to its craziest legislators. His Lone Star biography is important, timely, and most important, riveting.

At the start of Schulman’s fifth novel, scientist Frankie Burke has just won a MacArthur grant and has been invited to pursue her pioneering theory — that the children of cheating women have an evolutionary advantage — among a midwestern camp of bonobos. But there are complications: a history of endometriosis, a surprising love affair, and finally a catastrophic dust storm. Oh, and we’re in a near future in which our eyes are implanted with cameras, food is dispensed through 3-D printers, and climate change a terrifying succession of traumas. As the kids say, it’s a lot, but Schulman pulls it off beautifully.