How do you create a memorable female character? It helps if you get it right from the very beginning, as Joseph L. Mankiewicz did in his screenplay for All About Eve when he introduced the woman who would be played by Bette Davis. “The CAMERA follows the bottle to MARGO CHANNING,” wrote Mankiewicz in his stage directions. “An attractive, strong face. She is childish, adult, reasonable, unreasonable — usually one when she should be the other, but always positive.”

It’s an indelible description of a complicated woman, one so persuasive that you’d even think Margo exists outside the margins of Mankiewicz’s pages … and in a way, she would, since Davis eventually brought to life what the writer first put to words. Not every screenwriter takes the time to pen such a vivid character introduction — some include few details other than an estimated age or a few quick adjectives, preferring instead to let their dialogue do the talking — but many of our most famous screen women were originally created in those carefully composed sentences that few besides the actress, her writer, and their crew were lucky enough to read.

It’s always fun to get a peek behind that curtain, but why settle for just a peek? Vulture has rifled through countless old screenplays to find the descriptions for 50 notable female characters, which we present to you below. The women are young and old, heroine and foe, star and supporting character, but they were all born on the page. Some interesting, sometimes frustrating trends emerge in the details; you may not be shocked to learn that most of these writers spend far more time describing the female character’s level of beauty than they do her male counterpart’s. But whether the descriptions are well-written or problematic, they offer plenty of insight into how Hollywood views women and creates roles for them.

One of the best ones is this wonderfully evocative introduction of the faded movie star played by Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard:

Norma Desmond stands down the corridor next to a doorway from which emerges a flickering light. She is a little woman. There is a curious style, a great sense of high voltage about her. She is dressed in black house pajamas and black high-heeled pumps. Around her throat there is a leopard-patterned scarf, and wound around her head a turban of the same material. Her skin is very pale, and she is wearing dark glasses.

Few women but Audrey Hepburn could truly live up to this description in Breakfast at Tiffany’s:

The girl walks briskly up the block in her low cut evening dress. We get a look at her now for the first time. For all her chic thinness she has an almost breakfast-cereal air of health. Her mouth is large, her nose upturned. Her sunglasses blot out her eyes. She could be anywhere from sixteen to thirty. As it happens she is two months short of nineteen. Her name (as we will soon discover) is HOLLY GOLIGHTLY.

One of the best screen couples has got to be Nick and Nora Charles from The Thin Man. If you haven’t had the pleasure of falling in love with them onscreen, rest assured that this description of Nora will do it for you:

NORA CHARLES, Nick’s wife, is coming through. She is a woman of about twenty-six… a tremendously vital person, interested in everybody and everything, in contrast to Nick’s apparent indifference to anything except when he is going to get his next drink. There is a warm understanding relationship between them. They are really crazy about each other, but undemonstrative and humorous in their companionship. They are tolerant, easy-going, taking drink for drink, and battling their way together with a dry humor.

You only get one chance to make a first impression … unless there’s a sequel, in which case you’ll have to be reintroduced. Let’s look at the way James Cameron described Sarah Connor over the arc of two Terminator movies, starting with the first film, when this humble waitress had no idea she would go on to become the mother of the resistance:

SARAH CONNOR is 19, small and delicate-featured. Pretty in a flawed, accessible way. She doesn’t stop the party when she walks in, but you’d like to get to know her. Her vulnerable quality masks a strength even she doesn’t know exists.

Compare that to the buff, hardened warrior woman Linda Hamilton portrayed in Terminator 2: Judgment Day…

SARAH CONNOR is not the same woman we remember from last time. Her eyes peer out through a wild tangle of hair like those of a cornered animal. Defiant and intense, but skittering around looking for escape at the same time. Fight or flight. Down one cheek is a long scar, from just below the eye to her upper lip. Her VOICE is a low and chilling monotone.

How about a few other screen women you wouldn’t want to cross? Here’s the description of goth hacker Lisbeth Salander from the screenplay for The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo:

Lisbeth Salander walks in: A small, pale, anorexic-looking waif in her early 20’s. Short black-dyed hair - pierced eyelid - tattoo of a wasp on her neck; probably several more under her black leather jacket - black t-shirt, black jeans, black Caterpillar boots … This isn’t punk fashion. This is someone saying, Stay the fuck away from me.

Meet the young heroine of The Hunger Games, who conveys toughness and grit from the jump:

KATNISS EVERDEEN walks past without turning. She’s 15, lean and hungry, with steel-gray eyes and a long dark braid — a fighter, robbed of her little-girl years long ago.

Mo’Nique’s Oscar-winning role in Precious was just as vivid on the page:

MARY — INCREDIBLY LARGE, OILY SKIN, UNKEMPT HAIR, AND WEARING A GRIMY HOUSE DRESS sits on the couch with her back turned to Precious. This mass of woman looks as if she is one with the furniture — if not the entire apartment.

This description of Faye Dunaway’s Bonnie in Bonnie and Clyde, alone in her bedroom, establishes where the character is headed even before we see her rob a single bank:

Blonde, somewhat fragile, intelligent in expression. She is putting on make-up with intense concentration and appreciation, applying lipstick and eye make-up. As the camera slowly pulls back from the closeup we see that we have been looking into a mirror. She is standing before the full-length mirror in her bedroom doing her make-up. She overdoes it in the style of the time: rosebud mouth and so forth. As the film progresses her make-up will be refined until, at the end, there is none.

And this introduction of Gina Gershon’s character in the Wachowskis’ sexy thriller Bound minces no words:

Leaning against the back of the elevator is Corky, a very butch-looking woman with short hair and a black leather jacket. She is a lesbian and wants people to know it.

Can You Guess This Famous Female Character?

We'll give you the way she's introduced in the screenplay. You tell us who she is.

Film is a visual medium, and a screenwriter might have plenty of reasons to describe a female character’s look beyond simply flattering an actress or enticing the reader. Still, it’s striking to see how often and how thoroughly the female characters’ physical attributes are dissected. (There’s even a Twitter account devoted to it.)

Take this description by Quentin Tarantino of the first woman we see in his film Death Proof, the radio DJ played by Sydney Tamiia Poitier:

A tall (maybe 6ft) Amazonian Mulatto goddess walks down her hallway, dressed in a baby tee, and panties that her big ass (a good thing) spill out of, and her long legs grow out of. Her big bare feet slap on the hard wood floor. She moves to the cool rockabilly beat as she paces like a tiger putting on her clothes. Outside her apartment she hears a “Honk Honk.” She sticks her long mane of silky black curly hair, her giraffish neck and her broad shoulders, out of the window and yells to a car below. This sexy chick is Austin, Texas, local celebrity JUNGLE JULIA LUCAI, the most popular disc jockey of the coolest rock radio station in a music town.

Margot Robbie got her breakout role in The Wolf of Wall Street, and the screenplay essentially treats her character like Leonardo DiCaprio’s avaricious Jordan Belfort would:

We see NAOMI, 24, blonde and gorgeous, a living wet dream in LaPerla lingerie. Naomi licks her lips; she’s incredibly, painfully hot.

There’s no question James Cameron was a bit sprung on the Na’vi warrior he created for Zoe Saldana to play in Avatar:

Draped on the limb like a leopard, is a striking NA’VI GIRL. She watches, only her eyes moving. She is lithe as a cat, with a long neck, muscular shoulders, and nubile breasts. And she is devastatingly beautiful — for a girl with a tail. In human age she would be 18. Her name is NEYTIRI (nay-Tee-ree).

One of the most complicated female protagonists in recent years has to be Lisa, the high-school student played by Anna Paquin in Kenneth Lonergan’s underseen masterpiece Margaret. She is brash, foolish, and passionate, perpetually throwing herself into situations she knows little about but quick to speak on them with total certainty. You might expect some of those attributes to work their way into Lonergan’s description of Lisa. Instead, he simply wrote this:

On LISA COHEN, just 17. Not the best-looking girl in her class but definitely in the top five.

Many screenplays try to hedge their female character’s beauty, lest she seem so gorgeous as to be unattainable. Perhaps the woman doesn’t know how pretty she is, or there’s a slight imperfection added to make her relatable. The exact calibration of these female characters’ beauty begs a reference to Goldilocks: They’re hot, but not too hot.

Take Buttercup from The Princess Bride:

Buttercup is in her late teens; doesn’t care much about clothes and she hates brushing her long hair, so she isn’t as attractive as she might be, but she’s still probably the most beautiful woman in the world.

Or Saoirse Ronan’s immigrant from Brooklyn:

One of the front doors opens, and out slips EILIS — early twenties, open-faced pretty without knowing it.

Meg Ryan’s character from When Harry Met Sally was similarly naïve to her own beauty:

Driving the car is SALLY ALBRIGHT. She’s 21 years old. She’s very pretty although not necessarily in an obvious way.

While the screenplay for True Lies fusses over the appearance of Helen Tasker (Jamie Lee Curtis) like a henpecking mother:

To call her plain would be inaccurate. She could be attractive if she put any effort into it, which doesn’t occur to her.

Then again, there are plenty of female characters who have an almost apologetic relationship to their own looks and try to mitigate them somehow. Take the Julia Stiles character from 10 Things I Hate About You:

KAT STRATFORD, eighteen, pretty — but trying hard not to be — in a baggy granny dress and glasses.

She’d probably have lots to talk about with Celine, the character played by Julie Delpy in Before Sunrise and its two sequels:

Strikingly attractive, she plays it down by wearing no make-up, a loose-fitting vintage dress and flat shoes.

And maybe they could exchange style tips with Zooey Deschanel’s elusive love interest in (500) Days of Summer:

SUMMER FINN files folders and answers phones in a plain white office. She has cropped brown hair almost like a boy’s but her face is feminine and pretty enough to get away with it.

It’s startling to discover that even some of the most beautiful women in the world, asked to play some of the screen’s sexiest characters, were still not immune to the Goldilocks description. Take Whitney Houston’s besieged singer in The Bodyguard:

RACHEL MARRON finally rises from the sofa. It’s a bit of a shock to see that she is only about thirty years old. A young woman. Not beautiful, not ugly. Unique only in that she is immediately interesting. A Superstar.

Or Sharon Stone’s iconic murderess in Basic Instinct, who is judged against a character introduced in the previous scene and found a bit wanting:

CATHERINE TRAMELL is 30 years old. She has long blonde hair and a refined, classically beautiful face. She is not knockout gorgeous like Roxy; there is a smoky kind of sensuousness about her.

But guess which character is described with care, cinematic attention, and not a single description of her sex appeal? Nomi Malone from Showgirls!

Her name is NOMI MALONE. She looks from a distance like a kid. She stands along the Interstate, outlines in the shadows of the setting sun. She’s got a big American Tourister in front of her with a sign on it that says: “Vegas.” The suitcase looks like it’s been dropped from a plane or something. She’s wearing a baseball cap, a worn black leather jacket, torn jeans, and time-kissed cowboy boots. She’s got her thumb out.

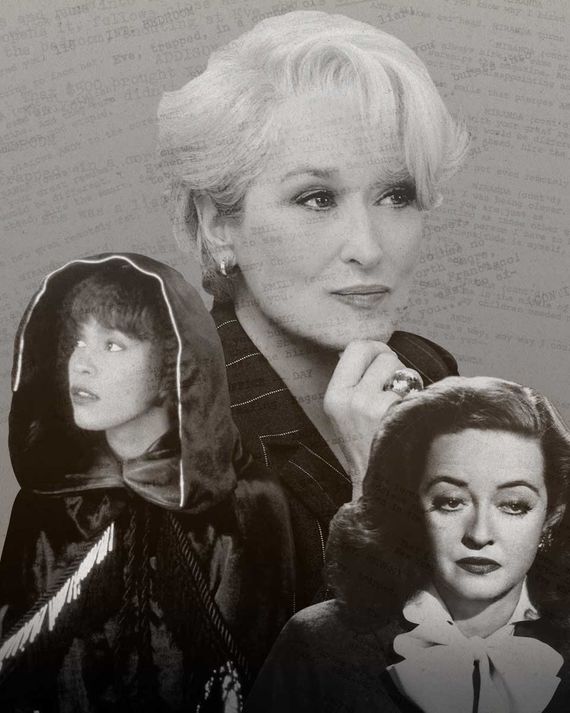

Should we move on from Showgirls to Meryl Streep? As befits the woman who is considered our greatest living actress, several of the characters she has played have received memorable screenplay introductions. The Devil Wears Prada gives us glimpses of Streep’s intimidating editrix until the full version is unveiled:

We see more flashes of MIRANDA… $2,000 crocodile Manolos, Chanel jacket, perfect hair, fabulous Harry Winston earrings… [until] MIRANDA steps out of the elevator and for the first time we see her head-on. MIRANDA PRIESTLY, in all her glory. She is stunning, perfectly put together, a white Hermes scarf around her neck. MIRANDA’S look is so distinctive you can spot her a mile away. She is unlike any other beautiful woman, singularly MIRANDA.

In the farce Death Becomes Her, here’s how Streep’s vain leading lady is brought onstage:

CUT TO the Actress’s face, and the picture on the Playbill isn’t exactly from yesterday. MADELINE ASHTON, fortyish, has just reached the point where age is beginning to encroach on her incredible looks. She’s elegant, she’s beautiful, but if you look closely behind her eyes in a quiet moment, you’ll notice something else. She’s terrified. Right now she’s singin’ and dancin’ up a storm, seemingly without benefit of training in singin’ or dancin’.

And this description of Streep’s character in It’s Complicated is a total distillation of writer-director Nancy Meyers and her heroines.

JANE is mid-fifties and has embraced that fact. She knows 50 is not the new 40 and because of that, she is still described by all who know her as beautiful. Everything about this woman’s appearance screams “solid.”

Julia Roberts isn’t necessarily thought of as a fashion plate, but if you peruse the screenplays for her films, you’ll realize that many of her most famous characters express themselves through what they wear. First up, Pretty Woman:

VIVIAN turns and stares at herself in a grainy, cracked bedroom mirror. She is twenty years old and a prostitute. Make-up applied to give her a hard, older look doesn’t quite succeed. She’d be innocently beautiful without it. She is wearing tiny shorts, a tight tube top, thigh high boots. She stares at herself, not really liking what she sees.

In My Best Friend’s Wedding, Roberts is more subtly costumed, but the way she dresses is meant to indicate high-functioning disarray:

JULIANNE POTTER, almost 28, wears her favorite bulky sweater over a bunch of other stuff she pulled together in fifteen seconds. She is unkempt, quick, volatile, scattered, and beneath it all, perhaps because of it all, an original beauty. Dark liquid eyes, a cynical mouth, slender expressive fingers.

And then, of course, there’s her unconventionally costumed legal crusader in Erin Brockovich:

How to describe her? A beauty queen would come to mind — which, in fact, she was. Tall in a mini skirt, legs crossed, tight top, beautiful — but clearly from a social class and geographic orientation whose standards for displaying beauty are not based on subtlety.

Some of the most endearing character descriptions are of girls navigating the path to adulthood. When we meet Jennifer Grey’s character in Dirty Dancing, the script emphasizes how far she still has to go:

Next to Lisa is her sister, BABY, an endearingly unkempt puppy of a seventeen year old, whose face has the unguarded responsiveness of a child. At the moment, she is hunched in her corner and all we see is her shaggy hair, her scruffy sandals, and the book she’s reading — “THE PLIGHT OF THE PEASANT.”

Writer-director Gina Prince-Bythewood introduces the two leads of Love & Basketball as children, but when she fast-forwards to high school, where Monica and Quincy are now teenage basketball stars, her female lead gets this reintroduction:

On the floor, MONICA, dribbles down court. Just EIGHTEEN, her athletic figure has a few curves, but her loose jersey does little to show it off. Her hair is a mess and her knees are dark with bruises. A small scar is visible on her cheek.

In Beetlejuice, Winona Ryder’s Lydia may still be young, but she feels more fully formed as a person than the immature adults around her:

Lydia, age 14, is a pretty girl, but wan, pale and overly dramatic, dressed as she is in her favorite color, black. She’s a combination of a little death rocker and an ’80s version of Edward Gorey’s little girls. She has a couple of expensive cameras around her neck and is already taking photographs of the moving men. Lydia is cool, Lydia is sullen, Lydia is her father’s daughter by his first marriage. Lydia is usually about half-pissed off. But underneath… we like her a lot.

Many screenplays promise us that we’ll eventually like the female character, especially if she’s introduced in a place of conflict. Take Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio’s estranged wife in The Abyss:

A slender woman in her early thirties. She’s attractive, if a bit hardened, dressed conservatively in a skirt and jacket. Meet LINDSEY. Project Engineer for Deepcore. She’s a pain in the ass, but you’ll like her. Eventually.

The character introduction for Rachel Weisz in The Mummy is even more insistent:

Standing at the top of a tall ladder between two of these rows and leaning against one of the bookshelves, is a rather uninteresting British GIRL: eye-glasses, hair-in-a-bun, long boring dress, your typical prudish nightmare. This is EVELYN CARNAHAN. We’re going to fall in love with her.

But not every screenplay feels the need to declaim quite so much when introducing the love interest. Sometimes, the description is so beguiling that you start to fall in love yourself. Who wouldn’t lean forward at this introduction of Susan Sarandon’s character in Bull Durham?

ANNIE SAVOY, mid 30’s, touches up her face. Very pretty, knowing, outwardly confident. Words flow from her Southern lips with ease, but her view of the world crosses Southern, National and International borders. She’s cosmic.

Or how about Shirley MacLaine’s winsome elevator operator in Billy Wilder’s The Apartment, who you’d like to get to know?

She is in her middle twenties and her name is FRAN KUBELIK. Maybe it’s the way she’s put together, maybe it’s her face, or maybe it’s just the uniform — in any case, there is something very appealing about her. She is also an individualist — she wears a carnation in her lapel, which is strictly against regulations. As the elevator loads, she greets the passengers cheerfully.

In 1944, when Wilder’s classic noir Double Indemnity came out, this description of Barbara Stanwyck’s femme fatale was awfully hot:

Phyllis Dietrichson stands looking down. She is in her early thirties. She holds a large bath-towel around her very appetizing torso, down to about two inches above her knees. She wears no stockings, no nothing. On her feet a pair of high-heeled bedroom slippers with pom-poms. On her left ankle a gold anklet.

Some love interests, like Karen Allen’s in Raiders of the Lost Ark, can be summed up in two sentences:

She is MARION RAVENWOOD, twenty-five years old, beautiful, if a bit hard-looking. At this moment, however, that look does not hurt.

Some don’t even get that much: In the script for Star Wars, Princess Leia is merely described as a “lovely young girl.” When her portrayer, Carrie Fisher, eventually embarked on a successful screenwriting career, she lavished far more attention on the characters she scripted.

One of those characters is the one we’ll end with: Postcards From the Edge’s Doris Mann, played by Shirley MacLaine and based on Fisher’s own mother, Debbie Reynolds. You can imagine a slow grin spreading on Fisher’s face as she brought this one home:

A woman is running down the hallway, wailing, everything flying — purse, wig askew, blouse untucked, false eyelashes removed. Clearly this woman was caught mid-something for the apparent emergency. She is DORIS MANN, about 60, formerly beautiful and more than somewhat currently. She was an enormous star in the ’50s and ’60s and bears that mark. She is currently very upset, theatrically so. Cutting a wide swath as she makes her way down the hall — things dropping out of her purse, mostly makeup, a pack of cigarettes. People watch her as she moves by moving aside to avoid impact. Doris Mann is very upset. Perhaps she has lost a shoe.

Kyle Buchanan joined our friend John Horn, host of KPCC radio’s entertainment show “The Frame,” to talk about producing this story and what it reveals. You can listen to their discussion here.