In 1976, three years after leaving his native USSR for Israel, Vladislav “Slava” Tsukerman relocated for good to New York City. In terms of Gotham’s gloriously filthy heyday, he had arrived right in the sweet spot: a bit closer to the release of The Velvet Underground and Nico in 1967 than David Dinkins’s election to the mayor’s office in 1990, and the same year Martin Scorsese unveiled Taxi Driver. Upon its release, that film was hailed as an instant New York masterpiece, an unsparing field report from the open hell-pit currently referred to as Times Square. But Slava didn’t live in midtown; he claimed himself a piece of the Village a stone’s throw from Union Square, and downtown, it was an entirely different scene.

“The first time I visited New York, I instantly fell in love,” the 78-year-old filmmaker recalls during a phone call with Vulture. “I liked everything about it: the atmosphere of international culture, where nobody cares about your accent and everybody has the same position as you. I have a great nostalgia for the New York of the ’70s and ’80s. New York culture was on the top, and you could feel it. There was creativity in the air, drifting in from the galleries in the art district and the incredible technical productions on Broadway and the whorehouses where you could find all manner of sexual activity. It all wafted downtown.”

After six years spent breathing in these heady fumes, Slava exhaled Liquid Sky over the course of six months in 1982. With little more than a paltry half-million dollars and the sum of their estimable wits, Slava and his team of clutch collaborators (including, most notably, co-writer/actress Anne Carlisle; Slava’s wife and co-producer and co-writer Nina Kerova; cinematographer–VFX wizard Yuri Neyman; and his wife, production designer and costume designer Marina Levikova) constructed a monument to a strain of hedonism in vogue a few 1 train stops south of Scorsese’s pimps and working girls. Slava instead trained his lens on the art freaks and New Wavers for an outrageous slice of ’80s-counterculture Zeitgeist.

But watching Liquid Sky in the present — as many New Yorkers will starting April 13, when the Quad Cinema begins screening a commendable new restoration of the film — metro-savvy viewers might let out a chuckle. Go to any bar in north Brooklyn on a Saturday night, and you’ll find crowds who have spent hundreds trying to look as poor as the flamboyantly attired extras that Slava drafted from the street. (Bona fide junkies pogo during the numerous dance scenes, portraying what Slava calls “images of themselves.”) All of which is to say that for the fashion-forward, post-gender, genre-busting Liquid Sky, its time has finally come.

____

Slava makes it sound so simple, as if you’re the stupid one for not having come up with it first. “I had an idea for a movie about aliens from outer space, and Nina had an idea for a movie about the female orgasm. We put them together.” As these concepts gestated, he and Kerova had made the acquaintance of a model, performance artist, and bohemian “It” girl named Anne Carlisle, and they agreed that she would have to be their star. Together, the trio mapped out a bizarre script replete with surreal jags of sex and violence, wholly original while at the same time indebted to both sci-fi B movies and The Panic in Needle Park.

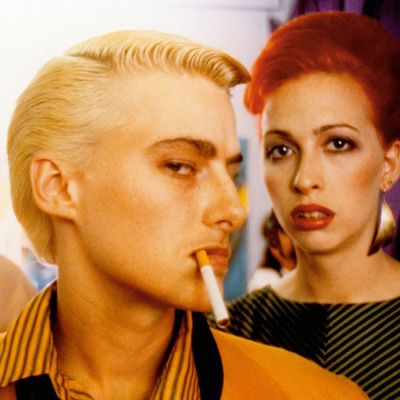

Carlisle does androgynous double duty as Margaret and Jimmy, two rival models orbiting around a nightclub teeming with avant-garde weirdos straight from an Oingo Boingo video. Margaret’s alarmed to find that her sexual partners have started dropping dead the moment they achieve climax, unaware that extraterrestrials parked on her roof are feeding on the dopamine release of orgasm. Meanwhile, Jimmy’s looking for a fix of his own, slithering through his scenes in search of coke or, preferably, heroin in between photo shoots. (Elsewhere, a German scientist watches it all happen while politely fending off increasingly aggressive advances from Jimmy’s extremely horny mom. Don’t worry about it.) Carlisle’s two-front performance, in turns unaffected to the point of Nico-ishness and soap-opera melodramatic, was more than a hanger for the pinnacle of New Wave style — it’s an object lesson in queer gender theory.

Slava’s hallucinatory aesthetic gambits befit the outré nature of the material, such stuff as narcotized dreams are made of. For starters, the aliens’ slayings take the form of an Abstract Expressionist computer readout in which concentric splotches of color bleed into and then out of one another. Between the mad experiments with black light, the proto-glam hair and makeup, and the manipulated exposures, any given frame could be isolated and mounted on an art-school undergrad’s dorm-room wall. Of particular note is the film’s score, composed in part by Slava himself, a demonic carnival of early synths. “I wanted an electric circus, but not exactly like that,” Slava explains. “It should sound computerized. I spoke with a lot of people who played primitive synthesizers, and they showed me how they could use it to create the sound of an orchestra, but I wanted that primitivism. I couldn’t understand why they’d want to hide it.”

This may sound like control-freak behavior, but Slava’s tireless work ethic betrayed his earnest intentions. He claims to have muscled through 18-hour days during production on Liquid Sky, joining Neyman to assist in special-effects work late into the night after filming had wrapped. (That he remained sober throughout this process may be the most shocking aspect of all: “No drugs on set. I don’t know about the personal life of everyone involved, but as far as I know, Liquid Sky was probably the only drug-free production in New York at the time.”) Everyone involved had poured a lot of themselves into making the film, and Slava was intent on making sure their efforts wouldn’t be for naught. He had succeeded in bottling all the flamboyance and depravity that charmed him in his first years as an American, but selling the public on it was another matter entirely. Bringing his neighborhood to the world would not be nearly as difficult as getting the world to come through his neighborhood.

___

Slava toured from Montreal to Sydney as Liquid Sky bounced between festivals, picking up a slew of awards along the way. But in the days before the social-media insta-takes flooding out of press screenings could create a buzz in seconds flat, building a viewership was a bitter ground war.

“It first opened in Los Angeles, and critically, it was very successful,” Slava says. “The audiences loved it, too, but there weren’t very many audiences there to love it. The young people who would watch a film such as this weren’t in Los Angeles, they were in New York. When we opened in New York, we changed the promotional strategy completely, we had all these ways to spread word of mouth and promote the film without using much money.”

With a street team made up of friends and other arbiters of taste in the local underground, Slava found the midnight-movie crowds that the film had been waiting for. As he tells it, every showing in the first week sold out, an auspicious start to a run that would last four years. While the cash flow ran at a trickle, it lasted long enough to recoup the film’s costs nearly four times over. But even as the film’s influence grew, single-handedly spawning the musical micro-genre termed “electroclash,” a paucity of home-video options stunted its expansion. Unless one of the thoroughly garbled VHS tapes circulating around college campuses floated your way, Liquid Sky was the sort of film murmured about and seldom seen.

Enter the good folks of Vinegar Syndrome, a boutique restoration company dedicated to preserving films off the beaten path and making them accessible to the public. After spending the better part of two decades ingratiating themselves with Slava, Vinegar Syndrome earned his approval and began the laborious process of revitalizing a vital film. Working with Neyman, the technicians prettified Slava’s original print without sacrificing its integral dinginess, perking up the Day-Glo reds and blues back to their original lurid glory. (They’ve also prepared a Blu-ray release currently available to order.)

Prior to a preview arranged for curious members of the press, I had only seen Liquid Sky via an online torrent of questionable provenance, and Carlisle more closely resembled a loose collection of polygons than a human woman. The vast gulf in quality between the new 4K treatment and that download might as well be the difference between watching the film and never having seen it at all. Better still, watching it at a small theater tucked away on 13th Street gives a viewer the impression that they’ve stumbled back in time to the fever-pitch ’80s — as if the remnants of danger can still be found in a New York of rising rents and ever-hastier storefront turnover, if only a person knows where to look.

___

Slava still lives in the same apartment near Union Square, heretofore having made the occasional appearance when a repertory house around town would trot out one of the precious few 35mm reels of Liquid Sky. The new surge in interest seems to have energized him, however. He’s been contemplating the idea of a sequel ever since he called “cut!” on the final take of the original, and after an extended creative stagnation, he’s found new inspiration. “For a while, I had no idea how to move the story forward,” Slava admits. “But times change, and I change.” He and Carlisle will soon complete the script currently in progress, at which point he’ll reembark upon the long, uphill battle to find funding — though he may face less resistance this time around.

As if evidence wasn’t already everywhere — in Kesha music videos and Gaspar Noé’s psychedelic Enter the Void, in hard-house audio sampling and the films of eternal art-punk teen Gregg Araki — the Liquid Sky rerelease is self-evident proof that the film’s cultural cachet has only grown. Even so, there’s a poetic irony to the fact that it should survive today as a time capsule permitting the new generation of hip kids to feel nostalgic for a past they never lived through. New York’s continuous ouroboros of self-cannibalization refashions derelict factories as chic nightclubs and turns gutted tenements into $14-a-pop cocktail bars; now that the island has been purged of Liquid Sky’s real-world referents, the oddballs having retreated to Queens or the deepest reaches of still-to-be-gentrified Brooklyn, the film is more valuable than ever before.

Some measure of crankiness is to be expected from anyone who’s lived in New York for more than five years, a precious and hard-won right. Slava has no interest in yelling at the Parsons undergrads and their heinously overpriced thrift-store jackets to get off his lawn, though. The ongoing fetishization of the era he helped define doesn’t bother him as much as it inspires him. The biggest stumbling block for Liquid Sky 2 was the rapid disappearance of the cultural space in which the original had germinated; where do you set a heroin flick after the city’s kicked its habit? The only way around the problem was through it. If the sequel ever sees the light of day, it’ll find Slava grappling with a modernity from which he has determinedly not insulated himself. Where he was once the art freak, he’s now the alien invader, bringing chaos from another place to an unsuspecting milieu in need of a good shake-up.

“Union Square used to be the market for drugs, and now it’s such a fancy area,” Slava quietly reflects. “All the streets surrounding used to be empty at times, and now it is always crowded. What really surprised me is how on University Place, I’ve seen every single store and restaurant change. Nothing lasts, not one. It’s a little bit depressing, but that’s normal.”