Get a bunch of acclaimed writers in a room together and delightful things will happen. That was the premise — and outcome — of the PEN America Festival’s recent “One Book, One New York: Authors in Conversation” panel, featuring writers Hari Kunzru (White Tears), Jennifer Egan (Manhattan Beach), Esmeralda Santiago (When I Was Puerto Rican), Imbolo Mbue (Behold the Dreamers), and filmmaker Barry Jenkins (who is adapting James Baldwin’s If Beale Street Could Talk). They were on hand to speak with host Jennifer Finney Boylan about their work as part of the 2018 One Book, One New York program, which is being run by the city of New York and Vulture.

(Now’s a good time to encourage you to go vote for which of those five books you want everyone in New York — and around the world — to read together this summer.)

Last year, 50,000 New Yorkers voted, and an even higher turnout is expected this year. “It’s wonderful to see this kind of response,” said Julie Menin, media and entertainment commissioner for New York City, before the PEN America Fest panel. “These books raise important issues regarding inequality, exclusion, immigration — themes that are so important to New Yorkers and important to be speaking about.”

An edited transcript of Finney Boylan’s conversation with the writers — about their process, the research they conduct before writing, and how New York has changed each of them — is below, along with a few select questions from the audience. But first, here’s some helpful background on each writer and book.

Hari Kunzru is the author of The Impressionist, Transmission, My Revolutions, Gods Without Men, and One Book candidate White Tears. White Tears tells the story of two young white men who are obsessed with black music, and it begins with one of them sampling an unknown singer in Washington Square Park, then doctoring that recording to make it sound like a long-lost blues recording from the 1920s. An old record collector then contacts the protagonists to let them know that the recording that they’ve created is actually that of a real long-lost musician, the mysterious Charlie Shaw.

Imbolo Mbue is the author of the novel Behold the Dreamers, which won the 2017 PEN Faulkner Award for fiction, and was named by the New York Times and the Washington Post as one of the notable books of 2016. It tells the story of two New York families: that of Clark Edwards, a white executive at Lehman Brothers, just before that institution circles the drain, and that of immigrant Jene Junga, Edwards’s chauffeur.

Barry Jenkins, originally from Liberty City, Miami, won the Oscar for Best Picture and the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay, for his 2016 film Moonlight. His book is If Beale Street Could Talk, by James Baldwin. Originally published in 1974, it tells the story of Tish, who is pregnant with the child of her fiancé Fonny, a 22-year-old sculptor, who begins the book behind bars for a rape he did not commit. If Beale Street Could Talk will be Barry Jenkins’s next film.

Jennifer Egan is the president of PEN America, author of A Visit from the Goon Squad, and winner of the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. Her One New York book is Manhattan Beach, a story set in her home borough of Brooklyn in the 1930s and ’40s, where her heroine Anna Kerrigan is working at the Brooklyn Navy Yard as part of the war effort. She finds her life intertwined with that of a gangster, Dexter Styles.

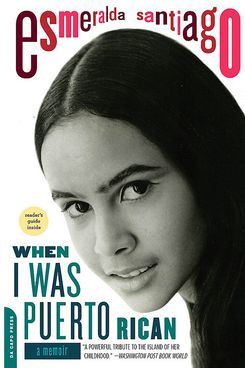

Esmeralda Santiago is the author of both of memoirs and novels. Her New York City One Book is the memoir When I Was Puerto Rican, and it tells the story of growing up in San Juan along with her 11 brothers and sisters, the infidelities of her father, and the courage of her mother.

Jennifer Finney Boylan: Let’s begin with a line from Imbolo’s novel: “Maybe I’m becoming another person.” To live in the city is to be aware of the way New York alters who we are. Who were you when you came to New York, and who are you now?

Hari Kunzru: Well, I was a newly single, slightly damaged writer who put all his stuff into a storage unit in East London.

Is that a redundancy? A damaged writer?

Kunzru: I needn’t have even specified. I came to live in a little studio apartment in the East Village and discovered that people talked to each other at the crosswalk. You don’t have a conversation with people in public space in London unless you’re actually insane. So this was a new thing for me, and when I now go back there, I’m the person who’s like making conversation in line at the grocery store.

Why the East Village? Is that just where you landed?

Kunzru: I had one of those lucky breaks where somebody said that they were moving out of this place. I took it sight unseen, and it was great. It was also at street level in the East Village, and I hadn’t kind of realized that I would basically be eavesdropping on every NYU breakup and every drug deal in the entire neighborhood.

Has that changed the way you write?

Kunzru: Completely. The English language is your instrument when you’re a writer, and I deliberately really tried not lose my accent, but the English I hear around me changed my vocabulary. Obviously there are different things that everybody knows; the boot of the car, the trunk of the car, and so forth. But I remember going into a bar in one of my first few weeks and they had all these craft beers. I said, could I have a Coney Island please, and they said, “It’s a Tiny Island? What is Tiny Island?” And there was a party where the entertainment consisted of getting me to say “breakfast burrito” with a hard T.

I wonder how New York changes the two men at the center of White Tears.

Kunzru: They are both kind of classic young hipster incomers, really. One is, at the time, of a very wealthy family, a family with roots in the South. And the other is a sort of suburban New Jersey boy, and they’re record producers. And they have this supposed love for everything that is old, everything that has the patina of age. Making new things feel old. The motor for this plot is their faking of a 1920s blues record. They put it out as if it’s an old record, thinking they’ve made a kind of calling card for their business. And instead, they may have channeled something from that is trying to make itself present.

They fall into this vortex, this meta-vortex. So they’re not who they were in the beginning.

Kunzru: No. In a way, this book is very much about me getting to know and love this place through sound, and through the kind of layers of musical history that’s here. And the central character, as he becomes more haunted by the past, becomes less secure in his present experience of the city, I guess would be one way of putting it. He sometimes is walking down the street, and it’s now. And at other times, he’s walking down the same street, and it can be 10 years, or 50 years, or 100 years ago. So he has these glimpses of previous version of the city. Washington Square Park, sometimes it’s a sort of blasted 1970s wreck, and the lower East Side is sometimes full of Jewish immigrants, and sometimes it’s what it is in the present day.

Imbolo, I’d like to ask you the same question. Who were you when you came to New York City? And are you the same person now?

Imbolo Mbue: Well, I used to live in New Jersey before I came here. I was having a hard time in New Jersey, and I thought, well, New York would probably be better. I was in my mid-20s. I moved to Harlem. I’m happy I stayed, but I thought about leaving. I thought New York was special, but too expensive, which is no news. The city did change me. I became, I don’t know, a tougher person. It was just a place I had to be tough. And I didn’t think about going back to New Jersey, but I thought, maybe I should move back to Cameroon. And I did not. That influenced my book a lot. Because my book is very much about being confident about New York City, and about going back to your home country.

When your character Neni says that line, “Maybe I’m becoming another person,” is she saying that as a good thing, that she’s changing? Is there sadness in it as well?

Mbue: No. It’s not a good thing. I think it’s some sort of, she’s saying that after having done things that she would not have done if she hadn’t moved to New York City. Which, I’m sure, you can relate. You find yourself doing certain things in this city, and you’re like, I did not do those things before, you know? That is what happened to Neni. It was mostly a survivor thing, like, being in New York City forced her to compromise on who she was. And I could relate to that myself.

Jenny, you came to New York City from Chicago. What was it you were seeking? And is it fair to ask if you found what you were looking for?

Jennifer Egan: Well, I didn’t really come here from Chicago, because I lived in Chicago only til I was 7. Then I lived in San Francisco, went to college in Philadelphia, and then lived in England for two years. Then I came to New York. So I got here, I had been … I had a scholarship to study in England for two years, so I’d had a very cushy life of checks rolling in, and getting to travel, and I had written a novel that no one had seen, that no one had read. I really kind of believed that it was just amazing. I hadn’t actually read it over very carefully. It looked great, as all manuscripts do. So I came here with a lot of … I just had no idea what I was doing. I rented a foam couch, I took someone’s place at an apartment in the Upper West Side, sharing it with someone I didn’t know.

I worked as a temp, which I thought would be incredibly lucrative. I couldn’t believe how high the hourly wage was. But I also didn’t understand how expensive New York was. So I had this idea that I could work three or four hours a day, and then write, and then of course, also my book would be going into publication. So it would all just kind of flow.

And what actually happened was, I would send this book out to an agent, and it came back so fast, it almost seemed like there hadn’t been time for it to even arrive in the mail. And then I also started sending it to friends and family to get some feedback, and I discovered that every single time I sent it someone, I couldn’t reach them. And of course this is before the internet and before cell phone, you actually could avoid people back in those days. So I began to get a sinking feeling, and then when my own mother became sort of AWOL briefly, I thought, “Oh dear. This is not good.” So I learned that the book was unreadable. I learned that temping … I basically had to temp constantly to support myself, and I often wonder … And I really didn’t have many friends in New York, no family, and I think, “Why did I stay?” But I think the answer is that I just adore New York.

I think that belief in your own genius, even when there’s no evidence, I think that’s fundamental to come to New York, because you really have to believe in something that doesn’t exist yet to get through those early times.

Egan: That belief was dashed within the first two weeks, and I still stayed.

Your novel Manhattan Beach is about the very profound changes that happened in New York City during those war years. Can you talk a little bit about that? How did New York change during that time?

Egan: Well, I should say first of all that what I really begin with when I write fiction, is a time and a place. So really, all I had when I thought about Manhattan Beach, and even when I sat down to start writing writing about New York during World War II, what provoked that curiosity was 9/11. The recognition of how abruptly a city can feel like a war zone. I mean, I just think that’s something very few Americans understand. We just don’t have a lot of collective memory of that. The waterfront was completely controlled by the military during the war, and that was the area that I was most interested in. The Brooklyn Navy Yard was the largest builder and repairer of allied ships in the world. They repaired about 5,000 allied ships, and built 17 battleships, including the U.S.S. Missouri, where the Japanese signed the surrender.

And one of the interesting things about researching this book was feeling more viscerally what some of these stories we’ve all heard really meant. The one I’m thinking of is women had opportunities that they hadn’t had before. They were not just invited but sort of begged to come and work in industrial jobs, and then they were all fired, and expected to go back and bake cookies, or whatever.

I work on an oral history project with the Brooklyn Navy Yard and the Brooklyn Historical Society, and luckily we were doing this between 2005 and 2010, so we actually had the chance to interview maybe 20 women who had worked at the Navy Yard. They were in their 80s then. And many of them, of course, have passed away since.

There was one woman named Ida, who was a welder, and she clearly had loved welding. She talked about it kind of sensually, even at 80-something. Women were not allowed on ships for the first couple of years that they worked at the Navy Yard, because there was fear about what would happen if men and women worked close together in these very tight spaces. But the women protested. I mean, they’re working at a navy yard, and in fact, it ultimately behooved the Navy to have them on the ships, because the women were so limber and tended to be smaller. And Ida was very small. So she was an incredible welder, and had a lot of seniority, but the women were all fired before the war ended, and Ida was working class, and she thought, “I don’t wanna go back to the phone company. I wanna keep welding.”

Every time she applied for a job, she was laughed at and treated with contempt, when she had been praised and promoted for doing exactly that work, even six months or a year earlier. Those were the kinds of ways that the city changed.

Esmeralda, I suspect that you’re not the same person you were, when you were 13. Do you remember who you were then?

Esmeralda Santiago: The girl who arrived here on August 21, 1961, to be precise. It was raining, and I had been born in the San Juan metropolitan area, but my family lived in the rural part of Puerto Rico. Very rural. We had no electricity, no running water. And that’s what I thought I would be the rest of my life. My younger brother had an accident with his foot, and the medical system there was telling my mother they were going to amputate his foot, and so my mother said, “I’m going to New York,” where her family lived. I now realize that my brother’s accident was the precipitating factor. She did go back when he was a lot better, but then, she came back to get us, and to bring us to New York.

I remember arriving on that evening in August, and maybe a day or two later was allowed to go out into the street just to see where I was, and this young girl was skipping rope, and started talking to me, and said, “Are you España?” And I’m like, “No. I’m Puerto Rican.” And she said, “Well, you know, people like us are Hispanics here in the United States.”

And this was probably one of the most terrifying moments of my life, because all of a sudden I was like, wait a second. Yesterday I was Puerto Rican, and just because we came across the ocean, I am now something else? And indeed that was the big question for me for years after that. Who was that girl? Who am I now? Who do I want to be? And how do I create the person I want to be. So it was a series of traumatic events that I remember almost cinematically, they were so powerful, and I know that it wasn’t just that I was España, as opposed to Puerto Rican, puertorriqueña, it was that my culture in Puerto Rico was expecting something completely different from a girl of my age.

And when I arrive in New York, the expectations are completely different. And I had to kind of figure out, whose expectations do I follow? My mother’s expectations, which are very specific to the culture? The expectations of my cohorts, who are all wearing makeup and short skirts, and I was not allowed to? The United States society that said, “If I saw the word Puerto Rican in the newspapers, it was always something bad.” I had to figure out which one of these expectations do I accept for myself. How do I create the person I want to be, given that almost all the expectations are negative? I had to become a new person.

When you go back to Brooklyn now, is there anything that’s familiar to you now?

Santiago: Oh, it’s a different country. I could barely really recognize it. It was very poignant for me; my husband and I live north of New York City, in the country, and my mother used to say that we left Macun, the rural part of Puerto Rico, but maybe brought Macun to the United States. As soon as my children were old enough, they all moved back to Brooklyn. But the Brooklyn that they lived in was so different that they could not connect it to their mother’s experience.

I’m very eager to hear about James Baldwin and the New York that the characters in If Beale Street Could Talk live in. Is that also a banished place? Are there ghosts of it still here?

Barry Jenkins: I don’t know if it’s a banished place. The city is very different physically than it was in 1974, 1972, 1968, by the time period that the novel traverses. Tarell McCraney, the playwright who wrote In the Moonlight, Black Boys Look Blue, came and saw the film recently. Tarell has spent a lot of his life in New York, Miami, and London. He said, you know, it’s very interesting, because the New York physically that existed at the time of this book does not exist in the same way. One of the main characters, Fonny, is trying to find a loft. You know, there’s literally a line that says they’ve got lofts standing empty all over the East Side. And now? Hell no. They have $5 million lofts that are not empty all over the East Side.

So physically, it’s very different, but Tarell made this beautiful comment after seeing a cut of the film. He was like, “Oh, you made this New York. It’s not a New York of places. It’s a New York of faces.” And I think the faces that existed in the time of Baldwin are still present in the New York that I see today, and the New York that we made this film about.

Beale Street has these tensions in it. It’s a very dark book. But there’s also, I think, tremendous optimism. Fonny and Tish believe in their child. They believe in love, so it’s a very romantic book. Do you think that kind of optimism in the face of all the trouble in the world is a New York way of looking at the world that’s changed? Or do you think it’s still around?

Jenkins: There’s a duality in the book. I think Baldwin had a lot of very serious things to say, but he uses this very beautiful couple in the purest love you could possibly imagine in juxtaposition to a New York that was, over the course of the next ten years, slipping into a very dark place. I think this sort of hope or optimism is running directly counter to a certain cynicism of both the city and the country. With what African-Americans were going through at the time, and for me, it was a very rich thing to undertake, because in one scene you have just the purest example of young love. And that’s in the emotional undertaking of the characters. But also, thing two, in the vocation. You know, Fonny is a sculptor from Harlem, who leaves high school and just wants to find a loft on the East Side to sculpt, and he takes his young bride with him. He wants to make a world of two things: of his wife, and his vocation.

And yet, the city at that time, or certain elements of the city, decide to squash that dream in a certain way. And I think in the hands of James Baldwin, it’s almost like a bunch of billiard balls on a pool table, and some of them are very pure, and some of them are very dark, and he just throws them all on the table and watches how beautifully and horrifically they clash and clang. And I think that as you go around the city today, you can still see remnant of some of those things. It’s a much more cleaned up New York City, but I do think the tension that was present when Baldwin wrote this wonderful piece of material is still there.

The question of the research in the story is one I think all writers struggle with, even those of us who are telling stories of our own lives, or of people very much like ourselves. I thought that maybe we could talk about the issue of imagination and research. Hari, how much historical research, or other research, was necessary to create White Tears?

Kunzru: Obviously it’s a book that deals with the past, and there was quite a lot of straightforward library research. But there was also a lot of research I had to do about sound and about how one thinks about places in terms of sound. The most unusual thing I did was I developed a habit of recording my walks around the city. I’ve got these little microphones that fit into your ear like earbuds, and they’re little microphones. When you turn your head the recording changes slightly, so when you play it all back, you can really hear how you move through a space. And I would go walking around downtown, and then listen to my walks.

We’re visual creatures. We’re normally dominated by our visual sense, and that’s how we navigate the world. And when suddenly your hearing is the thing that dominates everything, you realize you’re going through these spaces that are changing very rapidly. You don’t realize necessarily that there are birds in the tree above you on a busy downtown street. Or that you’re passing bits and pieces of people’s conversation. Jenny, you were saying you’re an eavesdropper. I am too.

Egan: I want those ear mics.

Kunzru: They’re very good because you can pick up from quite a long way away. The moral hazard is considerable.

What’s your favorite sound of New York?

Kunzru: I like Washington Square. I like all the different phases of walking into Washington Square. Also, actually, zigzagging either side of Canal. There are all sorts of different tiny micro spaces around there. It changes from one minute to another.

Imbolo, Behold the Dreamers is set during the financial crisis of 2008. Did you go back and research that whole era? The fall of Lehman Brothers, and that whole era of economic collapse? Or was it still pretty fresh in your mind?

Mbue: I had to do a lot of research about Lehman Brothers, because I’d never worked on Wall Street. I tried to get a job at Goldman Sachs. I couldn’t get a job there, so maybe it was some sort of revenge on Wall Street. After Lehman Brothers collapsed, there was a court-appointed examiner who did all this research on what happened behind the scenes there, and I read a lot of that document, because it contained the emails between the Lehman brothers. I was able to get a sense of how they spoke to each other, what was going on behind the scenes.

But my novel is also about immigrants from my hometown. From Limbe, Cameroon. That one was not as hard, because I know what they’re lives are like. I came to America from that same town. I lived in Harlem, like them. I live in a very bigoted world also.

But writing about the Lehman Brothers executive and his family wasn’t that easy, because I do not know that world. I was writing about people whose lives are nothing like mine. I remember what it was like the first time I went to Park Avenue. I’d never seen wealth like that in my life. So that fascination, I think, is what really drove me. This fascination with the Über-wealthy. Before I came to New York City, I had been living in New Jersey. And when I went to Columbia was the first time that I met rich people. American rich people, that level of wealth and that life. So when I went to the Upper East Side, I was following them around. Looking at their Louis Vuitton handbags. What they wear, and how they talk.

I didn’t know any chauffeurs, I didn’t interview any chauffeurs. But from the stories from the babysitters and the housekeepers and the nannies, I was able to get a sense of what it’s like to work for those kinds of families. I wanted to get a sense of them, not just as the wealthy people, but as human beings. It was a long journey for me to really come to relate to them. To see them as not the Über-wealthy, not the one percent but just as ordinary New Yorkers, that took a while.

Barry, you’ve won an Oscar for Best Screenplay Adaptation, so I’m guessing it’s something that you’re pretty good at. Can you talk about adapting Baldwin, and how close to your source material you’re staying?

Jenkins: It was difficult. I grew up worshiping at the altar of James Baldwin. And this is the first time that any Baldwin piece will be adapted in the English language. So it’s a lot. Not to put any more responsibility on myself, but it was a lot. I was trying to coalesce the thoughts and idea and the book into something that felt like cinema, and not like literature.

Because the book is nonlinear. It’s very point of view. You’re in Tish’s head for a lot of his novel. Film is not the best artistic vehicle for interiority. Baldwin’s stock in trade is the interior lives of his characters. So it was actually a great challenge. It’s one of the most rewarding things I’ve ever done as an artist, to take that interiority, the interiority of a master storyteller, and translate it onscreen. There’s this very simple passage in the book, where Fonny is sculpting, and I have the lines memorized. It’s very simple. Fonny is working on the wood. It’s a very soft wood. He doesn’t want to defile the wood. And I was like, I need to visually translate that. And so we took the roof literally off the set, and Fonny lives in a basement apartment, but this is heightened imagery, and we poured light through the ceiling.

James [Laxton, the cinematographer] had been on the F line, and some woman or man was playing the saxophone, playing their soul through this saxophone. He took out his iPhone and recorded it, and it’s played in minor keys, and then there’s all these arpeggios, and this song descends, and as it descends, the train comes into the station from afar. You just hear this rumble. Stephan James is sculpting to Baldwin’s words, and some person who I will never meet is playing a saxophone underground, and the rumble of New York City is in my film.

Jenny, Manhattan Beach feels like an incredibly well-researched book. Could you talk a little bit about how you went about doing that research and recreating Brooklyn in the ’40s?

Egan: I don’t write about myself, or people I know ever. But what I do use are my memories of times and places. So I think just instinctively, I needed to build up a reserve of textures and anecdotes — and in a way, memories, but that weren’t actually mine.

I got interested in diving because I had visited the Navy Yard, and learned that diving was an important part of ship repair, and looked at a picture of someone in a Mark V diving apparatus. It’s very archetypal, with the spherical helmet. And I saw that picture, and I had this particular kind of excitement that I’ve learned to pay very close attention to, because it means that something is going to lead somewhere in fiction. So in 2009 I went to this reunion of divers, and one of the things that the reunion offers to participants is the chance to wear the old equipment, the Mark V, and dive in a tank.

So these two guys, Vietnam vets, offered to dress me in the Mark V. And I of course said yes. It’s a very heavy outfit. It’s not really an outfit, it’s almost like a machine that is assembled around you. It weighs 200 pounds. So it was extremely uncomfortable to wear it, and I stood up very briefly. Luckily, someone had a camera for that millisecond that I was on my feet. Years later, I started writing about diving, and I could write about how uncomfortable that dress was.

Esmeralda, When I Was Puerto Rican was published in 1993, decades after you came to America. Did you need to do research to recapture the person you’d been, or was she right there waiting for you?

Santiago: Well, I was there, and I knew what happened. So I didn’t really have to do research the way I have had to do research for a historical novel that I wrote many years later. I approached writing the memoir from the perspective of, if I remember something, then I should write it up. So my first draft was something like 1,000 pages.

Later on, I did do a little bit of research for the memoirs, in terms of, well … I was a teenager. What was the most famous song in 1968? I remembered the music, but I didn’t have it specific to that summer, let’s say. So I did go back, and I tried to figure out, well I know “Respect” was one of my favorite songs, but when was that? And when was that on the radio all the time? And so I just kind of fact-checked a lot of my memories. But it’s a very interesting thing about being a memoir writer is you’re writing what you remember, what you saw, and what’s your story. And if I had consulted my siblings, the story would have been completely different, because I’m the eldest of 11. We had the same mother, but we all had a different mother. I am a whole generation apart from my youngest sibling, and so we remember things in such different ways.

There’s real suffering that’s going on in Puerto Rico, and our government’s neglect is making the suffering worse. What can your childhood tell us about the Puerto Rico of today?

Santiago: I was sure that my generation was the last generation to grow up the way I grew up. And it turns out that since September 20, 2017, Puerto Ricans have been living the way that I grew up, with no access to good water. No access to power. Neglected. And I just did not believe that that was possible again in Puerto Rico, after so many years of attempt to make progress there. So it’s a very painful thing for me to realize that we have gone back, you know, 40, 50 years, in terms of what people have to learn about living on this island. I knew how to build a fire so that we could cook. There’s at least two whole generations who didn’t know how to do that.

And they’ve had to learn and realize that they might have to learn skills that they will need for the rest of their lives if this neglect continues, because Puerto Rico is not going to recover in just a few weeks, or a few months. It’s gonna take years, in addition to the fact that so many have had to leave the island for various reasons. It’s all very emotional. I’m shaking myself talking about it. They’ve had to abandon their home. I was taken from Puerto Rico as a child. I had no choice. But a lot of the people that I know have had to leave, and nobody ever wants to leave home, really. Even if home is awful, you just kinda dream that things are gonna be good in our home.

Audience member: This question is for Jennifer Egan. Do you think in the U.S. we are coming into a moment where stories by black Americans and other people of color are being institutionally elevated without the need of an obvious entry for white readers? I think, even when looking at a moment in movie like Moonlight, I had to ask myself, was is it a fluke? Or are we really championing these stories, and wanting to see those more on the screen?

Egan: I guess what I would say is I hope so. I published my first novel in 1995, so I’ve been publishing for a while. I’ve been in New York and sort of observing the literary scene, to some degree. And I actually feel that things really are changing in that way. Like something is actually different. And that’s wonderful. As a white person, I may not be the best qualified to speak to whether that change feels real or visceral. I’m an observer. But, it looks to me, and it feels to me, to the degree that I can feel it, like it is changing. And I feel that that is the best thing for all of us.

Jenkins: I don’t think it’s a fluke in the sense that there’s about to be a new Census. I think if it’s done correctly, you’ll see that the architecture that we think of as America is not the America we actually live in, despite the election. You know, more people voted for the other candidate. So it’s not the America we actually live in. And so, as far as it pertains to Moonlight, you know, whenever this question comes up, the thing I always like to say is, it’s like the Pepsi blind taste test, or whatever the hell it was. Like, if I say, “Oh, Moonlight won Best Picture.” It won Best Picture because of political correctness, or they had to correct course after #OscarsSoWhite, and so forth.

But if you just said Movie A won Best Picture, and I gave you whatever metrics we could actually find, it means it’s all critical opinion. But if I said the movie with the highest Rotten Tomatoes score in this year won Best Picture, or with the highest Metacritic score in this year, the movie that won this critic’s guild, that critic’s guild, that critic’s guild. Critics in New York, L.A., the National Board of Review, this movie won Best Picture, you wouldn’t question it. But if I said a $1.5 million movie, made by a second-time filmmaker about a boy whose mom’s into crack cocaine won Best Picture, then you go, “Oh, they won Best Picture because it’s a movie by second-time filmmaker in the projects about a boy whose momma’s into crack cocaine.”

So, I think that’s one thing, but nah, it’s not a fluke. I don’t think so. But it’s the way we box things. It’s really easy to allow things to boxed into a certain way, and then another way.

Audience member: This is for Imbolo. What is your opinion about this renaissance of African writers in diaspora, and do you feel optimistic that it will be easier for a new generation of African writers to get published and get their stories told?

Mbue: I am. I mean, I grew up within African culture, so it’s strange how something just surfacing in the West is “new,” right? Oh, Africans can write? Yes. Yeah. I mean to me, as a child, the classics were, you know, Cry Beloved Country. I’d never heard of Tolstoy. But I also think it’s important that we don’t put all Africans in one basket. I mean it is a very different experience. I mean, NoViolet Bulawayo, the author of We Need New Names — she’s from Zimbabwe, and it’s a different experience.

There’s a scene in my novel where I address what happens when people find out I’m from Cameroon. “Oh my God, I know somebody who went to Uganda!” Another person says, “When an American says that, you should tell them, ‘Oh. I have an uncle in Toronto.’ That way they can understand that.” It is very different experiences. I mean, I’ll say that I’m Cameroonian, which is what I am. It’s quite similar to Nigeria, it is also very different from Kenya, and the South Africans have a very different experience. And we wouldn’t put a Polish writer and a French writer in the same category, so we should allow African writers to at least express their unique cultures and celebrate that for what it is.