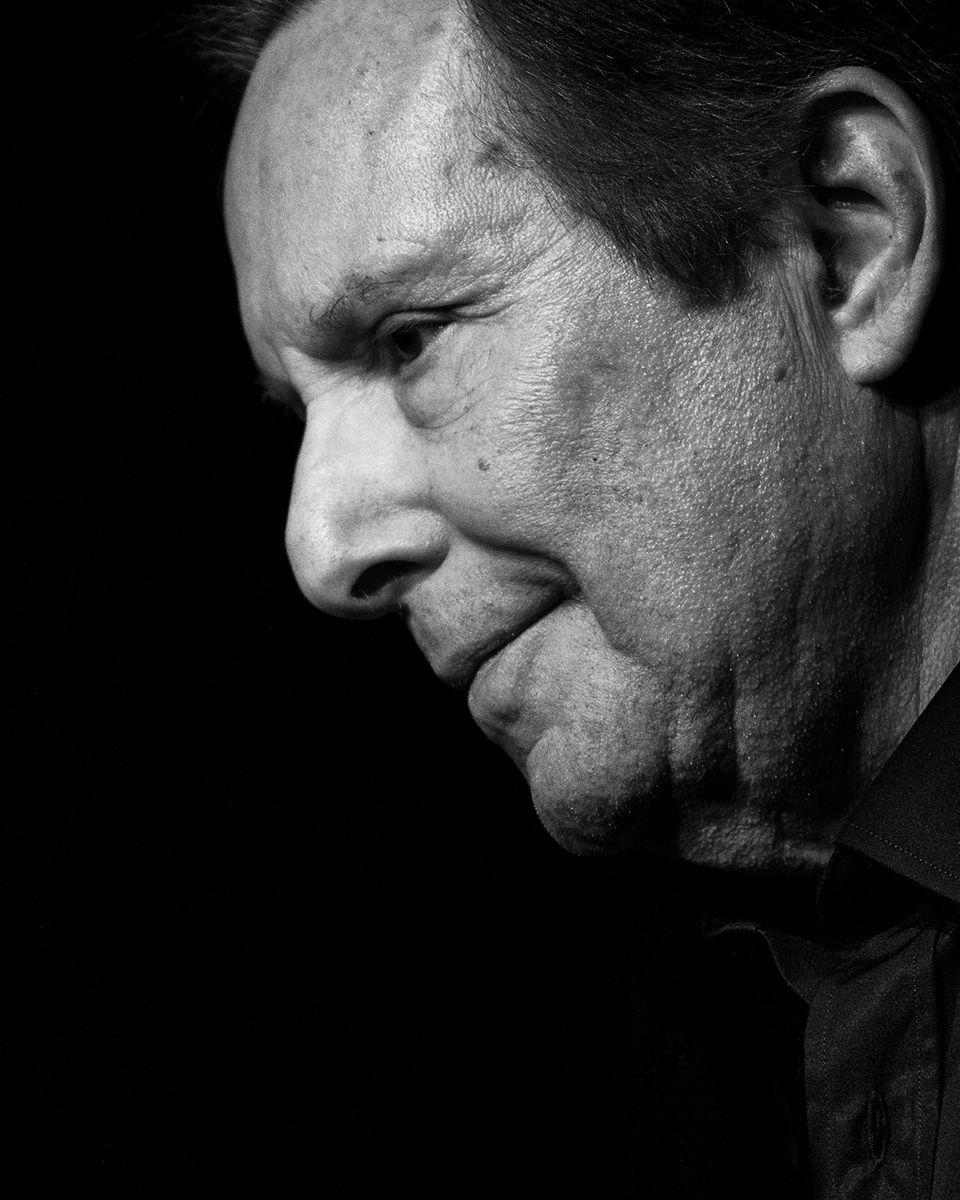

This interview was originally published in 2018. We are circulating it again in light of Friedkin’s recent passing.

In February of 2016, director William Friedkin — famous for The French Connection, The Boys in the Band, and The Exorcist, to name just a few films — was in Lucca, Italy, to receive the Puccini Award for achievement in opera. But Friedkin didn’t want to hole up in one city for the entire weeklong trip, so he did what one of our most accomplished living film directors can just casually do: He called a well-connected friend in nearby Rome, and asked if he could take a day to come to the city and meet the pope and the storied Vatican exorcist, the Reverend Gabriele Amorth. His theologian friend told him that the pope was unfortunately out of town, but that Father Amorth — a big fan of The Exorcist — would be pleased to meet him.

“I just had a lovely meeting with him for about an hour,” says Friedkin of his introduction to Amorth. “Then I came back here and went to the Vanity Fair Academy Awards party, and I was talking to Graydon Carter. I told him I’d been to Rome and met with a Vatican exorcist. He was immediately riveted and said, ‘Listen. Write this for Vanity Fair.’ I said, ‘I didn’t even record it. I’ll have to go back.’ And he said, ‘I’ll give you as much space in the magazine as you need.’” That interview in April 2016 led to Friedkin getting permission to film an actual exorcism with Amorth, which has now been turned into the new documentary, The Devil and Father Amorth. It’s a 67-minute presentation of what the director saw on May 1, 2016, when the reverend performed his ninth exorcism on a woman (called “Cristina” in the film) in order to liberate her from what she believes is demonic possession.

The movie opens with a look back at Friedkin’s myth-making classic, The Exorcist, and plays a bit like an episode of Unsolved Mysteries. It’s been critiqued as “pure tabloid,” but a filmmaker as skilled as Friedkin wouldn’t idly deliver pulp. Sure, there are theatrical flourishes of horror-film string-pulling, and the director’s guided narration does bring to mind Robert Stack, but he also comes across as entirely genuine in his desire to share this unbelievable story he caught on film — a woman, entirely convinced she’s in the grip of the Devil, writhing as she’s prayed over by a bishop and shouting in a voice that is markedly inhuman — and now wants you to consider what you’re capable of believing, too.

Vulture caught up with Friedkin in his Bel Air home — past three gated entrance points, atop a hill, and at the end of a private drive — to talk about an experience that he knows, much like story of Paul’s conversion in the Bible, “defies credulity.” He also shared with us why he didn’t have a camera with him on the day of his second harrowing encounter with Cristina, how much of a role exorcism iconography (like his own 1973 film) plays in how people manifest possession, whether or not he has a “moral right” to film someone in their most vulnerable spiritual hour, what he saw when he died that one time — and if Cristina’s guttural shouts were truly left unmanipulated during the documentary’s single-shot exorcism scene.

How did you come to know Father Amorth?

I was familiar with him through his writings and his reputation. He was the Vatican exorcist for 31 years. His title was Exorcist for the Diocese of Rome, and he founded something called the International Association of Exorcists, and of course [The Exorcist author and screenwriter] Bill Blatty and I knew about him for some time. But I had no contact with him at all until I went to see him, which happened quite by accident.

That was when you went from Lucca to Rome to meet with him, and the Vanity Fair interview you met him for came after, right?

Yes. I did a really extensive interview with him, after which I asked him if he would ever allow me to witness an exorcism, which they never do. No one is allowed, except the relatives of the person who is being exercised if they want to, and permission is never given. The church doesn’t advertise this. It’s not an entertainment. It’s not for the public. It’s a very private matter for Catholics. But he said, “Let me think about it.” And in two days I got an email from his superior at the Pauline Order, who said, “All right. On May 1 Father Amorth will be doing an exorcism at 3 in the afternoon and you’re invited to come.”

So I pushed my luck and I asked him to ask Father Amorth if I could film it, thinking, “No, you can’t film it.” Word came back, “You can film it. But I’m telling you, I’m not in favor of this.” But he said no crew and no lights. So I have a little Sony CX7 still camera that shoots high-definition video, and I went there and I filmed the exorcism. I filmed this close. I was two feet away from her. The mother was going to sit in that chair, but she got up and gave me her chair. I made a couple of little cuts in it. They’re frame cuts, because I was shooting obviously on automatic focus. I didn’t want to have to focus the lens, and I lost focus a couple of times. I just made a couple of quick, almost imperceptible frame cuts. That’s it.

Did you get any pushback from the Vatican about releasing this footage, since they really don’t discuss it?

If I had, they would go right into the trash bin. I’m not interested in either their support or denial. I would say they won’t. They don’t go public about this stuff. They might say to someone who is able to do interviews around the Vatican, “We would never give our permission to do this.” And they did not. I did not seek their permission. If I had I wouldn’t have gotten it. But Amorth did whatever he wanted to do.

Is it because he was so venerated that they basically gave him a pass, despite being outspoken in the ways you mentioned?

I don’t know if they put it that way, Jordan, but he did. And they didn’t try to stop him or squelch him because they knew he would make that public, and I think that everything he probably said was true — except the stuff about Harry Potter. He was against that, witchcraft or something. But no, they never tried to censor him, and they supported him. John Paul II was an exorcist. He left three cases to Father Amorth, one of whom he liberated, the other two he was treating at the time of his death, still. I met other priests that did exorcisms. I filmed one, but didn’t use it. He was not as profoundly spiritual as Father Amorth was. And I just believe that Father Amorth was authentic, which is not to say I can tell you there is a Devil, other than metaphorical, personified by people we know of throughout history.

Why do you think he allowed access at the end of his life?

We had a very strong communication. He liked me, and I not only liked, but respected him, and I think he was the most spiritual person I’ve ever met. And I think he may have had some feeling that I wouldn’t misuse this. At that time it was difficult for him to have people understand what he was doing. He was a severe critic of the Vatican. He regularly wrote and gave television interviews about the priest scandals, about a murder in Vatican City, other problems he had with the church, and they never touched him. He also wrote about things that he thought weren’t very good, like Harry Potter and stuff like that.

But he did like The Exorcist a lot.

Because of what I said. He thought it helped people to understand what he did, and I gave him an Italian copy of it, a DVD. And so he allowed me to film this. I didn’t know what I would ever do with it or anything.

Oh, so there was no intent to distribute this when you made it?

No! I thought, “I’m doing this because I can with my own camera on my own nickel.” I didn’t know what I would ever do with it, if anything. I didn’t know what it would be. I had never seen, obviously, an exorcism before I made the film, but after I filmed it I decided I would take it to four of the leading brain surgeons in the country, including the guy who is in charge of the brain-mapping project where they codify and identify the problem areas of the brain; and three brain surgeons, one from Israel; and some of the leading psychiatrists in the country. One was the editor of the DSM-IV, the other the DSM-V, the head of the Columbia School of Psychiatry, and the head of the New York Psychiatric Association.

Did you think they would be more dismissive of what you were asking them to consider?

They were black and white. The psychiatrists in the DSM-IV and V now recognize demonic possession. It’s called dissociative identity disorder, demonic possession, and if someone comes in and thinks they’re possessed they don’t say, “You’re not possessed. We’ll give you some medication and some therapy.” They give them therapy and medication, and an exorcist. There are very few such cases, but they do exist here, and the brain surgeons had no idea what this was, which shocked me. They said they would not give this woman an MRI. There’s no point. While everything originates in the brain, this wasn’t a problem in her brain. This wasn’t something they could operate and remove. This wasn’t a lesion in the temporal lobe, or epilepsy.

You asked one of the doctors in your documentary what his relationship with God was. So what’s yours?

I’m interested in Jesus. I’m not a Catholic, but I’m interested in Jesus, yes. I strongly believe in the teachings of Jesus as expressed in the New Testament, by the people who wrote the gospels and Paul. I’m not a Catholic. I don’t know anything, but neither does anyone else. No one knows anything about the eternal mysteries, how we got here, why we’re here, is there an afterlife. Is there a heaven and a hell? Who knows? Recently the pope was quoted as saying there’s no hell, and he didn’t walk it back, but the church did. I don’t know if there’s a hell. Neither does he!

So going into the exorcism with Father Amorth, were you skeptical or open-minded?

Both.

And how did what you saw affect you?

Ultimately, it went from fear in me to empathy, complete empathy, and how it’s changed me is I’ve had a much deeper inner sadness ever since I saw that. And I did have the impulse to let people see it and make of it what they will. I’m not saying that I believe there is a Devil. I certainly believe there is evil, and that bad things happen to good people. She is a good person, and productive, and there it is.

I was somewhat skeptical, but not of [Amorth]. There’s certain people you just believe in their veracity. You may be right. You may be wrong, but certain people you know are bullshitting you from the get-go, and others not necessarily.

And Father Amorth wasn’t bullshitting you?

I think he totally believed in what he was doing, and anyone who got to have an exorcism or even an interview with him had to see certain medical doctors that he knew and he was aware of. And if they had no answer to the problems of these people, he would see them if he could, because he was in demand around the world. So I believed in him, but when that woman walked into the room with her family, I wondered, what in the hell is she doing here? She’s an architect. She was totally together. I would say very attractive in the way of an Italian movie actress, you know. And more importantly, totally together, and I didn’t know what she was there for until the exorcism started, and she went into that state.

And that inhuman wail, that was truly the sound of her voice?

Totally.

There was no manipulation in postproduction at all?

I wouldn’t fuck around with that! That’s ridiculous!

I too was open-minded going into it, but whatever voice that is coming out of her during the exorcism — it’s too bizarre not to ask about.

It was to me, too!

My brain was just not accepting it as I watched.

Well, you’re a skeptic.

I’m not, though. I think it’s a self-defense mechanism to reject something horrifying like that.

Do you think I would put this thing on if — why do such a thing if it didn’t come across to me as something absolutely real?

So you think it wasn’t human?

It’s not her. I won’t say it’s not human. It wasn’t her.

She’s very reasonable in your conversation with her, very mild-mannered and seemed kind, but also very convinced that this was an action she needed to take.

Well, if you’d been told for years this was what you needed to do — but, no. Nothing was altered. Not picture or sound, just right out of the camera. I did take the picture to the same color timing house I use for all my films to bring it in the right spectrum of color, because I shot it with a still camera. I also shot a lot of it with an iPhone and a GoPro. They filmed me with more professional equipment when I went to do the interviews with the doctors.

What was it like in the room?

Terrifying.

But everyone else seemed so calm.

This was their ninth time.

Did you feel like you were in danger or like it could get out of control?

Possibly. It was possible, but five guys were holding her down, and they were sweating like crazy and you can see that in the film. And she could have come out of the chair but I don’t know what she would have done. At the end, when I went back to shoot what we call B-roll, I didn’t take my camera into this little church because she changed the time of the meeting six times, and I just wanted to go in and talk to her and see if it was all right to film her, because she had spoken to my Italian translator.

So you were just going to see if everything was okay, and that’s why you weren’t prepared to film in the church in Alatri?

Right. I didn’t know what was going to happen. I wanted to see how she was. My translator told me she was not in good shape on the phone. She changed the place of the meeting. So I just left my camera sitting where we parked outside the church.

And it sounded like her boyfriend, called Davide in the film, was also demonstrating signs of something like possession, too?

Yes. Different, though. Davide was about about six-foot-four, heavyset, built like a lineman, and he was holding her around the throat and the waist and she was in a folding chair in this empty church, dragging him around the floor towards me. And he would hold her back, but he was yelling, “Give us back the film! I want the film back!” And I would say, “I’m not going to give it back to you.” He would demand it, and she, in that voice, was saying, “No! I want this shown!” [adds monstrous voice] I want this shown! She sounded like that. I don’t know what that was.

And you said it was freezing in there?

It was freezing inside, and outside it was about 110.

So what do you think the role of iconography plays in the physical demonstrations of people who believe they are possessed?

She had never seen the film.

Do you think there is a feedback loop, though? People seeing things like The Exorcist, and mimicking that behavior — even subconsciously — when they believe they have been overtaken by the Devil?

Well, let’s put it this way, Bill Blatty invented exorcism and possession for the modern world. There was nothing of any consequence written about it, certainly not on a mass level. There were certain textbooks that referred to it. Nothing of a popular nature was written about it, and this became what people think about. Not only what I saw, but for example, I showed [the exorcism footage] to a couple of psychiatrists who said, “It looks authentic, but it doesn’t have the classical symptoms.” And I said, “What are the classical symptoms?” And they each said, “Well, the head spinning, and levitation.” And I remember saying, “Doctor, we invented that. Mr. Blatty wrote that and I had to find a way to film it.” But I never heard of it. I never heard of that happening.

Reading reviews of the documentary, people did seem to be assessing the veracity of Cristina’s possession symptoms based on what an exorcism “should” look like, which is what you created with The Exorcist and has been replicated across an entire subgenre of possession horror movies. Presumably, no one critiquing The Devil and Father Amorth for something like a trade publication has seen an exorcism in person, so what is it like having your nonfiction film being kind of fact-checked against a fiction film you made almost 50 years ago?

I’m not surprised by that. At least as many people are skeptical as are believers, and that’s not my problem. I just filmed and put out what I saw. I don’t know what this is. Maybe someday there will be a different terminology for it in the medical world, in the psychiatric world. There isn’t now. I have not read anything about it, and so I don’t know. I’m not surprised that there are or will be skeptics, but unlike fictional films, they are being called upon to determine whether they believe it or not. When you watch The Exorcist, you don’t have to believe it.

So if the original intent wasn’t even to release this in the world, by the time you decided to, what were you hoping would come of it?

I wanted people to see it. It’s that simple. That’s all.

A review I read said of The Exorcist that it “made the Devil real” again for people, and at least anecdotally it was a nice little recruitment tool for the Catholic Church. Did you hope at all for The Devil and Father Amorth to make the Devil real again?

I never thought about that line you just used. I don’t know if the Devil is real. I believe, as Father Amorth said, the Devil is metaphor. The Devil is not a person. The Devil is not a shape. He believes that he has spoken with the Devil on numerous occasions, but he himself says he has never seen the Devil, but the Devil is representative of evil that we know exists. One of the guys in the documentary is an author who’s written six books about the Devil.

The author you interviewed in the documentary, Jeffrey Burton Russell, he seemed very uneasy with you doing this. He seemed afraid for you.

He did say a very profound thing, which was, don’t mess with this stuff. He has done extraordinary research on the Devil throughout history, and that’s the nature of his six or so books, and various characterizations of the Devil. But I believe as Amorth said that the Devil is metaphor for profound evil in the world, but it also strikes me that because there is also goodness. And what I say at the end, if there are demons, there may be angels, but not physical. I don’t believe they’re flying around somewhere. I don’t know! Maybe they are! Maybe they are. I don’t know. It’s not given to us to know. I don’t know anyone that has really seen the Devil. Father Amorth claims he has had dialogues with the Devil, but the Devil is metaphor.

A number of years ago, I had a heart attack on the San Diego freeway, driving my car on the way to my office at Warner Bros. I didn’t know it was a heart attack because I had never had one, but a pain started in my left shoulder and went across to my right shoulder and it was completely debilitating and profoundly painful, like an elephant standing hard on your chest. And I remember I got the window of my car open. I couldn’t breathe. I got out of my car. I couldn’t move. I get back in and it was about five minutes to Warner Bros., but it took me close to a half hour, and I didn’t think I could make it.

There was an infirmary right at the entrance to the Barham Avenue lot, and I remember staggering out of my car into the infirmary, and I fell on the floor, and there were these paramedics around me immediately, trying to revive me. I remember losing all of my senses individually, and I remember reading about that, and that’s what happened. The last sense I lost was the sense of hearing. My eyes were closed and I couldn’t open them. I heard one of the paramedics who was pumping my chest say, “I’m not getting anything.” And I thought — I remember by thought process. It was “I’m dying. I’m absolutely dying. And I have done nothing important with my life.” And then it was gone.

And I swear to God I heard a voice. It was a woman’s voice, very soft woman’s voice, and it was saying, “It’s all right. It doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter.” And I was moving as though on an escalator to a very distant light. And then I woke up in the emergency room at St. Joseph’s hospital, and I thought I was in hell, because the pain was still there. I’m looking directly into these hospital overhead lights, and there were four or five doctors around me who had revived me. I had an oxygen mask, which I continually was ripping off, and I was dead for several seconds. Dead. Medically dead. And I remember the voice and the movement, and that’s similar to other accounts.

In the documentary, you talk about high occurrence of exorcisms or people seeking exorcism in Italy. Obviously, it’s a very Catholic country, and I think whether a person believes in hell or the Devil or not, your documentary is a very interesting way of considering the power of a shared belief system capable of creating its own reality, with subjective facts. For many devout Catholics, possession isn’t up for debate. It’s a fact of life. And we see the phenomenon of people subscribing to their own “facts” all the time. Possession is just a sort of magical version of what we see people willing to believe in echo chambers of their own beliefs.

I don’t know what you mean by subjective facts. Facts are facts. Or not!

I agree with you. And I think that in the age of fake news and media manipulation, someone watching The Devil and Father Amorth who is inclined to dismiss possession as too silly to believe, is ignoring how many people are galvanized by information that is literally advertised as “alternative facts.” A country filled with people under the sway of Catholicism believing at a high per capita rate that being taken over by a demon is a real threat does not seem crazy to me, given what I see people on the internet are willing to believe every day.

This has nothing to do with politics of any kind — left, right, center, none. This is an event that is religious-based, and has to do with the mystery of faith that people have or do not have. Now how does that drive me to a kind of moral right to show this film? I don’t know that there is one. That’s not something that as a filmmaker you have to consider. A filmmaker is drawn to a story. I wouldn’t fake something like that. I wouldn’t make that up. That is what I saw, and I thought, “Why should I just be the guy who saw this? I should share this.” Maybe it will bring some people closer to their faith, and maybe it will further remove the skeptics, but that isn’t my problem. It just really isn’t. It’s not going to make the plight of this woman any easier either way, or harder. She has that to contend with. She still seeks exorcism and has not been successful. But he was in a class by himself, Amorth. There are a lot of guys who’ve written books, articles, and given interviews saying that they’ve done exorcisms. I just don’t believe them. I don’t believe their accounts as I’ve read them.

Did your instincts as a narrative filmmaking feel like they helped you pull this together, or did you find yourself having to ignore certain instincts for the purposes of a nonfiction film?

No. I just shot what I saw. And I was led by my conscience to seek out doctors that I fully expected would debunk it and say exactly what the hell this was.

You thought you’d come out of this with answers?

Well, that this is all bullshit. Or, “Here’s what this is. It’s pamphlyotosis simpliani —” whatever the hell that is, but the psychiatrists shared with me a lot of literature on the subject that went into the conclusions of the DSM-IV and V.

And how did you consider the possibility of exploitation? You obviously had permission from everyone involved. Mom gave up her seat for you during the exorcism. You seemed to adhere to all the conditions put in place, but what do you think your responsibility was to the subject? Skeptics could say, “This is a mentally ill woman and this isn’t right.”

That’s their problem! Don’t ask me to either acknowledge or apologize for them.

But even believers could say, “This is a woman in her darkest spiritual hour and you are taking advantage of her vulnerability.”

Give me the names of the people who have said that.

I just want to know what you saw as your duty to Cristina.

It was much more difficult to decide to make The Exorcist film with what Blatty had written, which contains blasphemy. A 12-year-old child saying and doing blasphemous things, that had never been touched. The idea of the crucifix and the vagina in the same frame of film, there is clearly a moral consideration, and when you’re telling a story that you believe in and really want to tell, you don’t stop. You’re not stopped by moral considerations. She knew I was filming. I don’t want this to hurt her. All her family and friends know this is going on. She is in a very small religious town 100 miles or so south of Rome. It’s an Etruscan town, pre-Roman, with pictures of the saints outside all the houses, oil paintings of the saints under glass. So people are well aware in her community and her family is totally aware of what’s happening with her. If she was a public person living in the heart of Los Angeles or Manhattan I might have had a different consideration, but I don’t know.

This interview has been edited and condensed.