Their Eyes Were Watching God is required reading in high schools and colleges and cited as a formative influence by Toni Morrison and Maya Angelou. It’s been canonized by Harold Bloom — even credited for inspiring the tableau in Lemonade where Beyoncé and a clutch of other women regally occupy a wooden porch — but Zora Neale Hurston’s classic novel was eviscerated by critics when it was published in 1937. The hater-in-chief was no less than Richard Wright, who recoiled as much at the book’s depiction of lush female sexuality and (supposedly) apolitical themes as its use of black dialect, “the minstrel technique that makes the ‘white folks’ laugh.”

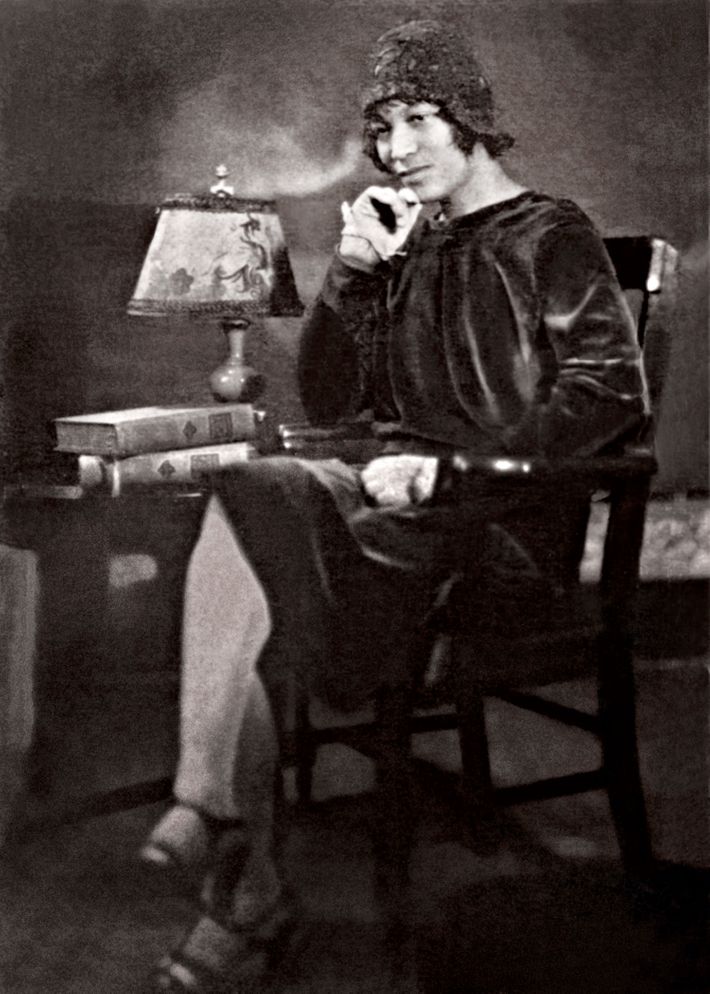

Six years earlier, Hurston had tried to publish another book in dialect, this one a work of nonfiction called Barracoon. Before she turned to writing novels, she’d trained as a cultural anthropologist at Barnard under the famed father of the field, Franz Boas. He sent his student back south to interview people of African descent. (Hurston was raised in Eatonville, Florida, which wasn’t the “black backside” of a white town, she once observed, but a place wholly inhabited and run by black people — her father was a three-term mayor.) She proved adept at the task, but, as she noted in her collection of folklore, Mules and Men, the job wasn’t always straightforward: “The best source is where there are the least outside influences and these people, usually underprivileged, are the shyest. They are most reluctant at times to reveal that which the soul lives by. And the Negro, in spite of his open-faced laughter, his seeming acquiescence, is particularly evasive … The Negro offers a feather-bed resistance, that is, we let the probe enter, but it never comes out.”

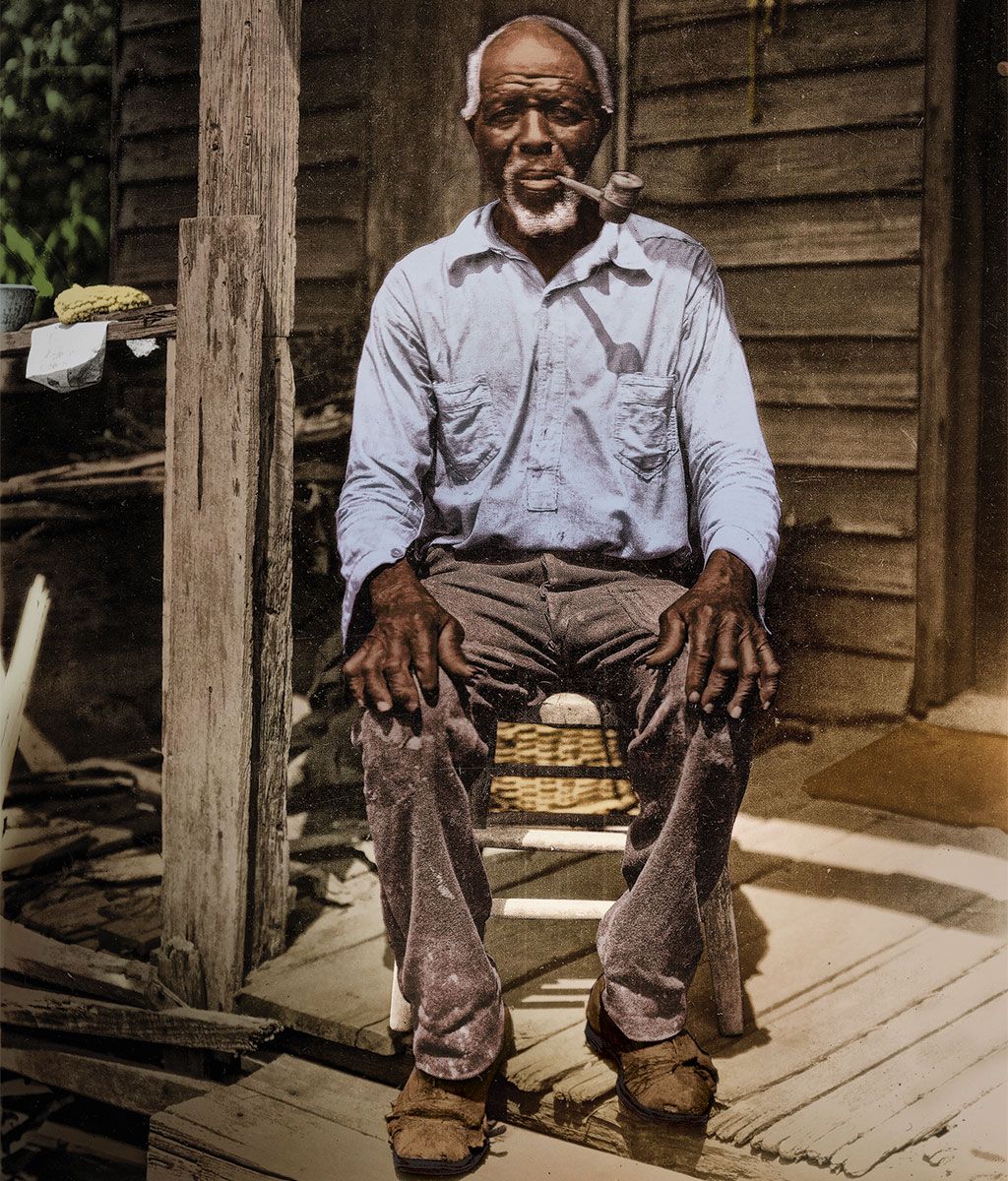

Barracoon is testament to her patient fieldwork. The book is based on three months of periodic interviews with a man named Cudjo Lewis — or Kossula, his original name — the last survivor of the last slave ship to land on American shores. Plying him with peaches and Virginia hams, watermelon and Bee Brand insect powder, Hurston drew out his story. Kossula had been captured at age 19 in an area now known as the country Benin by warriors from the neighboring Dahomian tribe, then marched to a stockade, or barracoon, on the West African coast. There, he and some 120 others were purchased and herded onto the Clotilda, captained by William Foster and commissioned by three Alabama brothers to make the 1860 voyage.

After surviving the Middle Passage, the captives were smuggled into Mobile under cover of darkness. By this time, the international slave trade had been illegal in the United States for 50 years, and the venture was rumored to have been inspired when one of the brothers, Timothy Meaher, bet he could pull it off without being “hanged.” (Indeed, no one was ever punished.) Cudjo worked as a slave on the docks of the Alabama River before being freed in 1865 and living for another 70 years: through Reconstruction, the resurgent oppression of Jim Crow rule, the beginning of the Depression.

When Hurston tried to get Barracoon published in 1931, she couldn’t find a taker. There was concern among “black intellectuals and political leaders” that the book laid uncomfortably bare Africans’ involvement in the slave trade, according to novelist Alice Walker’s foreword to the book, which is finally being published in May. Walker is responsible for reintroducing the world to a forgotten Zora Neale Hurston, who’d died penniless and alone in 1960, in a 1975 Ms. magazine essay. As Walker writes, “Who would want to know, via a blow-by-blow account, how African chiefs deliberately set out to capture Africans from neighboring tribes, to provoke wars of conquest in order to capture for the slave trade. This is, make no mistake, a harrowing read.”

One publisher, Viking Press, did say it would be happy to accept the book, on the condition that Hurston rewrote it “in language rather than dialect.” She refused. Boas had impressed upon her the importance of meticulous transcription, and while her contemporaries — and authors of 19th-century slave narratives — believed “you had to strip away all the vernacular to prove black humanity,” says Salamishah Tillet, an English professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Hurston was of the exact opposite opinion.

In any event, a dejected Hurston moved on to other projects, and the manuscript for Barracoon ended up languishing in her archives at Howard University. Until a few years ago, that is, when the Zora Neale Hurston Trust acquired new literary representation: Had any unpublished treasures been left in the vault? the agents wondered.

It may have taken 87 years for Barracoon to see the light of day, but Valerie Boyd, who wrote a well-regarded biography of Hurston called Wrapped in Rainbows in 2003, believes the timing is perfect for a writer “whose life’s work was to document and celebrate the lives of ordinary black folk.” “We’ve got an open bigot in the White House,” Boyd says. “We’re much more engaged with racial issues, with the resistance movement. A book like Barracoon says, ‘Yeah, black lives matter. They’ve always mattered.’ ”

Hurston seemed to assume that anyone deluded enough not to realize that would wake up if African-Americans were allowed to tell their own stories. (In one of her great quotes, she wrote that she always felt “astonished” when people discriminated against her: “How can they deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It’s beyond me.”) Here’s a scene of one of her early conversations with Kossula:

“I want to know who you are and how you came to be a slave; and to what part of Africa do you belong, and how you fared as a slave, and how you have managed as a free man?”

His head was bowed for a time. Then he lifted his wet face: “Thankee Jesus! Somebody come ast about Cudjo! I want tellee somebody who I is, so maybe dey go in de Afficky soil some day and callee my name and somebody dere say, ‘Yeah, I know Kossula.’ ”

“Barracoon,” by Zora Neale Hurston

Excerpt from Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” by Zora Neale Hurston. Published by Amistad Press. Copyright © 2018 by the Zora Neale Hurston Trust.

IN AFRICA

My father he name O-lo-loo-ay. He not a rich man. He have three wives. My mama she name Ny-fond-lo-loo. She de second wife. My mama have one son befo’ me so I her second child. She have four mo’ chillun after me, but dat ain’ all de chillun my father got. He got nine by de first wife and three by de third wife.

In de compound I play games wid all de chillun. We wrassle wid one ’nother. We see which one kin run de fastest. We clam de palm tree wid coconut on it and we eatee dat, we go in de woods and hunt de pineapple and banana.

One day de chief send word to de compound. He want see all de boys dat done see fourteen rainy seasons. Dat makee me very happy because I think he goin’ send me to de army. But in de Affica soil dey teachee de boys long time befo’ dey go in de army. First de fathers (elders) takee de boys on journey to hunt. Dey got to learn de step on de ground (tracks). De fathers teachee us to know a place for de house (camp site). We shoot de arrows from de bow. We chunkee spear. We kill de beastes and fetchee dem home wid us.

I so glad I goin’ be a man and fight in de army lak my big brothers. Every year dey teachee us mo’ war. But de king, Akia’on, say he doan go make no war. He make us strong so nobody doan make war on us. Four, five rainy seasons it keep on lak dat, den I grow tall and big. I kin run in de bush all day and not be tired.

CAPTURE

De King of Dahomey, you know, he got very rich ketchin slaves. He keep his army all de time making raids to grabee people to sell. One traitor from Takkoi (Cudjo’s village), he a very bad man and he go straight in de Dahomey and say to de king, “I show you how to takee Takkoi.” He tellee dem de secret of de gates. (The town had eight gates, intended to provide various escape routes in the event of an attack.)

Derefore, dey come make war, but we doan know dey come fight us. Dey march all night long and we in de bed sleep. It bout daybreak when de people of Dahomey breakee de Great Gate. I not woke yet. I hear de yell from de soldiers while dey choppee de gate. Derefore I jump out de bed and lookee. I see de great many soldiers wid French gun in de hand and de big knife. Dey got de women soldiers too and dey run wid de big knife and dey ketch people and saw de neck wid de knife den dey twist de head so it come off de neck. Oh Lor’, Lor’! I see de people gittee kill so fast!

Everybody dey run to de gates so dey kin hide deyself in de bush, you unnerstand me. I runnee fast to de gate but some de men from Dahomey dey dere too. I runnee to de nexy gate but dey dere too. Dey surround de whole town. One gate lookee lak nobody dere so I make haste and runnee towards de bush. But soon as I out de gate dey grabee me, and tie de wrist. I beg dem, please lemme go back to my mama, but dey don’t pay whut I say no ’tenshun.

While dey ketchin’ me, de king of my country (Akia’on) he come out de gate, and dey grabee him. Dey take him in de bush where de king of Dahomey wait wid some chiefs. When he see our king, he say to his soldiers, “Bring me de word-changer” (interpreter). When de word-changer came he say, “Astee dis man why he put his weakness agin’ de Lion of Dahomey?” Akia’on say to de Dahomey king, “Why don’t you fight lak men? Why you doan come in de daytime so dat we could meet face to face?”

Den de king of Dahomey say, “Git in line to go to Dahomey so de nations kin see I conquer you.”

Akia’on say, “I ain’ goin’ to Dahomey. I born a king in Takkoi where my father and his fathers rule. I not be no slave.”

De king of Dahomey askee him, “You not goin’ to Dahomey?”

He tell him, “No, I ain’ goin’. ”

De king of Dahomey doan say no mo’. One woman soldier step up wid de machete and chop off de head of de king, and pick it off de ground and hand it to de king of Dahomey. When I think ’bout dat time I try not to cry no mo’. My eyes dey stop cryin’ but de tears runnee down inside me all de time. I no see none my family.

All day dey make us walk. De sun so hot. De king of Dahomey, he ride in de hammock and de chiefs wid him dey got hammock too. Dey tie us in de line so nobody run off. In dey hand dey got de head of de people dey kill in Takkoi. Some got two, three head. Oh Lor’ I wish dey bury dem! I doan lak see my people head in de soldier hands; and de smell makee me so sick.

After a three-day forced march, the party arrived at the coast; Cudjo had never seen the ocean before.

When we git in de place dey put us in a barracoon behind a big white house and dey feed us some rice. We see many ships in de sea, but we cain see so good ’cause de white house, it ’tween us and de sea. But Cudjo see de white men, and dass somethin’ he ain’ never seen befo’.

De barracoon we in ain’ de only slave pen at the place. Sometime we holler back and forth and find out where each other come from. But each nation in a barracoon by itself. We not so sad now, and we all young folks so we play game and clam up de side de barracoon so we see whut goin’ on outside.

When we dere three weeks a white man come in de barracoon wid two men of de Dahomey. Dey make everybody stand in a ring. Den de white man lookee and lookee. He lookee hard at de skin and de feet and de legs and in de mouth. Den he choose. Every time he choose a man he choose a woman. He take sixty-five men wid a woman for each man. Den de white man go way. But de people of Dahomey come bring us lot of grub for us to eatee ’cause dey say we goin’ leave dere. We eatee de big feast. Den we cry, we sad ’cause we doan want to leave the rest of our people in de barracoon. We all lonesome for our home. We doan know whut goin’ become of us.

MIDDLE PASSAGE

Dey come and tie us in de line and lead us round de big white house. Den we see so many ships. We see de white man dat buy us. I in de last boat go out. Dey almost leavee me on de shore.

As the slaves were being rowed out to the Clotilda, the ship’s captain began to suspect that the Dahomey were going to trick him and try to recapture the people he’d just bought, so he gave orders to “abandon the cargo not already on board, and to sail away with all speed.”

When I see my friend Keebie in de boat I want go wid him. So I holler and dey turn round and takee me. When we ready to leave and go in de ship, dey snatch our country cloth off us. Dey say, “You get plenty clothes where you goin’.” Oh Lor’, I so shame! We come in de ’Merica soil naked and de people say we naked savage.

Soon we git in de ship dey make us lay down in de dark. Dey doan give us much to eat. Me so thirst! Dey give us a little bit of water twice a day. De water taste sour. (Vinegar was usually added to the water to prevent scurvy.)

On de thirteenth day dey fetchee us on de deck. We so weak we ain’ able to walk ourselves, so de crew take each one and walk ’round de deck till we git so we kin walk ourselves. We lookee and lookee and lookee and we doan see nothin’ but water. Where we come from, we doan know. Where we goin, we doan know. Cudjo suffer so in dat ship. I so skeered on de sea! De water, you unnerstand me, it makee so much noise! It growl lak de thousand beastes in de bush. De wind got so much voice on de water. Sometime de ship way up in de sky. Sometimes it way down in de bottom of de sea. Dey say de sea was calm. Cudjo doan know, seem lak it move all de time.

When the Clotilda arrived on the Alabama Gulf Coast, Cudjo and his fellow captives were ordered to stay below deck; they were taken ashore after dark and made to hide in a swamp for several days.

SLAVERY

Cap’n Tim Meaher, he tookee thirty-two of us. Cap’n Burns Meaher he tookee ten couples. Some dey sell up de river. Cap’n Bill Foster he tookee de eight couples and Cap’n Jim Meaher he gittee de rest. We very sorry to be parted from one ’nother. We seventy days cross de water from de Affica soil, and now dey part us from one ’nother. Derefore we cry. Our grief so heavy look lak we cain stand it. I think maybe I die in my sleep when I dream about my mama.

Cap’n Jim he tookee me. Dey doan put us to work right away ’cause we doan unnerstand what dey say and how dey do. But de others show us how dey raisee de crop in de field. Cap’n Tim and Cap’n Burns Meaher workee dey folks hard. Dey got overseer wid de whip. One man try whippee one my country women and dey all jump on him and takee de whip ’way from him and lashee him wid it. He doan never try whip Affican women no mo’.

We doan know why we be bring ’way from our country to work lak dis. Everybody lookee at us strange. We want to talk wid de udder colored folkses but dey doan know whut we say. Some makee de fun at us.

Cudjo’s owner, Jim, ran a shipping business on the Alabama River between Mobile and Montgomery, and Cudjo was eventually enlisted to “tote freight” on and off the boats.

Every time de boat stopee at de landing, you unnerstand me, de overseer, he go down de gangplank and standee on de ground. De whip stickee in his belt. He holler, “Hurry up, dere, you! Runnee fast! Can’t you runnee no faster dan dat? Hurry up!” He cutee you wid de whip if you ain’ run fast ’nough to please him. If you doan git a big load, he hitee you too.

De war commences but we doan know ’bout it when it start. Den somebody tell me de folkses way up in de North make de war so dey free us. I lak hear dat. But we wait and wait, we heard de guns shootee sometime but nobody don’t come tell us we free. So we think maybe dey fight ’bout something else.

Know how we gittee free? Cudjo tellee you dat. De boat I on, it in de Mobile. We all on dere to go in de Montgomery, but Cap’n Jim Meaher, he not on de boat dat day. It April 12, 1865. De Yankee soldiers dey come down to de boat and eatee de mulberries off de trees. Den dey see us and say, “Y’all can’t stay dere no mo’. You free, you doan b’long to nobody no mo.’ ”

Oh, Lor’! I so glad. We astee de soldiers where we goin’? Dey say dey doan know. Dey told us to go where we feel lak goin’, we ain’ no mo’ slave.

FREEDOM

After dey free us, we so glad, we makee de drum and beat it lak in de Affica soil. We glad we free, but we cain stay wid de folks what own us no mo’. Where we goin’ live, we doan know.

We want buildee de houses for ourselves, but we ain’ got no lan’. We meet together and we talk. We say we from cross de water so we go back where we come from. So we say we work in slavery five year and de six months for nothin’, now we work for money and gittee in de ship and go back to our country. We think Cap’n Meaher dey ought take us back home. But we think we save money and buy de ticket ourselves. So we tell de women, “Now we all want go back home. Derefo’ we got to work hard and save de money. You see fine clothes, you must not wish for dem.” De women tell us dey do all dey kin to get back, and dey tellee us, “You see fine clothes, don’t you wish for dem neither.”

But it too much money we need. So we think we stay here. We see we ain’ got no ruler, no chief lak in de Affica. Dey tell us nobody doan have no king in ’Merica soil. Derefo’ we make Gumpa de head. He a nobleman back in Dahomey. We ain’ mad wid him ’cause de king of Dahomey ’stroy our king and sell us to de white man. He didn’t do nothin’ ’ginst us. We join ourselves together to live.

Because Cudjo “always talkee good,” the Africans selected him to approach their former owners and ask for land in exchange for their years of free labor.

One day not long after dey tell me to speakee, Cudjo cuttin’ timber for de mill. Cap’n Tim Meaher come sit on de tree Cudjo just choppee down. I say, now is de time for Cudjo to speakee for his people. We want lan’ so much I almost cry and derefo’ I stoppee work and lookee and lookee at Cap’n Tim. He set on de tree choppin splinters wid his pocket knife. When he doan hear de axe on de tree no mo’ he look up and astee me,

“Cudjo, what make you so sad?”

I tell him, “Cap’n Tim, I grieve for my home.”

He say, “But you got a good home, Cudjo.”

Cudjo say, “Cap’n Tim, how big is de Mobile?”

“I doan know, Cudjo, I’ve never been to de four corners.”

“Well, if you give Cudjo all de Mobile, dat railroad, and all de banks, Cudjo doan want it ’cause it ain’ home. Cap’n Tim, you brought us from our country where we had lan’. You made us slave. Now dey make us free but we ain’ got no country and we ain’ got no lan’! Why doan you give us piece dis land so we kin buildee ourself a home?”

Cap’n jump on his feet and say, “Fool do you think I goin’ give you property on top of property? I tookee good keer my slaves and derefo’ I doan owe dem nothin.”

Cudjo tell de people whut Cap’n Tim say. Dey say, “Well, we buy ourself a piece of lan’. ” We workee hard and save, and eat molassee and bread and buy de land from de Meaher. Dey doan take off one five cent from de price for us.

We make Gumpa de head and Jaybee and Keebie de judges. Den we make laws how to behave ourselves. When anybody do wrong we make him ’pear befo’ de judges and dey tellee him he got to stop doin’ lak dat ’cause it doan look nice. We doan want nobody to steal, neither gittee drunk, neither hurtee nobody.

We call our village Affican Town.

FAMILY

Abila, she a woman, you unnerstand me, from cross de water. Dey call her Seely in Americky soil. I want dis woman to be my wife. Whut did Cudjo say so dat dis woman know he want to marry her? I tellee you de truth how it was. One day Cudjo say to her, “I likee you to be my wife. I ain’ got nobody.”

She say, “Whut you want wid me?”

“I wantee marry you.”

“You think if I be yo’ wife you kin take keer me?”

“Yeah, I kin work for you. I ain’ goin’ to beat you.” I didn’t say no more. We got married one month after we ’gree ’tween ourselves.

We didn’t had no wedding. Whether it was March or Christmas day, I doan remember now. We live together and we do all we kin to make happiness. After me and my wife ’gree ’tween ourselves, we seekee religion and got converted. Den in de church dey tell us we got to marry by license. In de Afficky soil, we ain’ got no license. So den we gittee married by de license, but I doan love my wife no mo’ wid de license than befo’ de license. She a good woman and I love her all de time.

Me and my wife we have de six chillun together. Five boys and one girl. Oh, Lor’! Oh, Lor’! We so happy. We been married ten months when we have our first baby. We call him Yah-Jimmy, just de same lak we was in de Afficky soil. For Americky we call him Aleck.

So you unnerstand me, we give our chillun two names. One name because we not furgit our home; den another name for de Americky soil so it won’t be too crooked to call. All de time de chillun growin’ de American folks dey picks at dem. Dey callee my chillun ig’nant savage and make out dey kin to monkey. Derefo’, my boys dey fight. Dey got to fight all de time. Me and dey mama doan lak to hear our chillun call savage. It hurtee dey feelings. When dey whip de other boys, dey folks come to our house and tellee us, “Yo’ boys mighty bad, Cudjo. We ’fraid they goin’ kill somebody.”

Cudjo meetee de people at de gate and tellee dem, “You see de rattlesnake in de woods?” Dey say, “Yeah.” I say, “If you bother wid him, he bite you. Same way wid my boys, you unnerstand me.” But dey keep on.

We Afficans try raise our chillun right. We Afficky men doan wait lak de other colored people till de white folks gittee ready to build us a school. We build one for ourself den astee de county to send us de teacher. Oh, Lor’! I love my chillun so much! I try so hard be good to our chillun.

Cudjo’s wife died about 20 years before Hurston interviewed him, and all six of his children were gone by then, too. Three died of illnesses, his only daughter at age 15; his youngest son was shot and killed; another died in an accident; and another left home one day to go fishing and never came back.

Cudjo’s Descendants

By Nick Tabor

Garry Lumbers, 61, was back in Mobile, Alabama, this year for Mardi Gras. For the big party on Tuesday night, he and his relatives staked out a spot at Kazoola, a bar named after Cudjo Lewis that opened downtown in 2016. A stranger in his 30s walked up and pointed to Lumbers’s T-shirt: It had a photo of Cudjo Lewis and his two great-granddaughters, Mary and Martha, taken in 1927.

“Yo, man,” the guy asked. “Where can I buy that shirt?”

“I had it made,” Lumbers said. “One is my mom” — Mary — “and one is my aunt.”

“Oh, man, I was ready to give up $30 for one of those.”

These days, Lumbers says, people in the Mobile area tend to know about the origins of Africatown (also called Plateau) — and about his great-great-grandfather Cudjo, who helped found it a few years after the Civil War — but they seem surprised to realize the family has living descendants. “The churches tell the kids the story during Black History Month, but they don’t know us,” he says.

Lumbers estimates that about 30 of Cudjo’s relations — all descendants of his son Aleck — still live in the 60 acres of Africatown, but I can attest that nobody seems aware of them. I called local ministers, government officials, and assorted others for several weeks before I tracked down Lumbers with help from a genealogist. Once in town, thanks to Lumbers’s driving directions, I found his distant cousin Tyrone Lewis, who lives in Magazine Point, where, he says, Cudjo and his fellow former slaves first took refuge when they were freed. I arrived at Lewis’s after dark, and stray cats slunk around my legs as I walked up to the small, wood-frame house and pounded on the door.

“Cudjo practically raised my dad,” Lewis tells me after his wife, Lana, invites me in. “He used to tell us how they were treated on the ship, how they’d made their life and built their land here.”

Lewis cleans floors for a living and preaches at a nearby church. But he and Lumbers say the lack of job opportunities has driven many family members away: some to Birmingham and Montgomery, others to Detroit and Chicago. Lumbers himself left in 2000 to join his mother, Mary, and sister in a bedroom community of Philadelphia, where he works in shipping and receiving.

Mary and her twin were in their early teens when Cudjo died, in 1935. Lumbers and Lewis were born more than 20 years later, but during their childhoods in the 1960s and ’70s, Africatown remained more of Cudjo’s time than theirs. Because there was no indoor plumbing, they bathed in claw-foot tubs and heated water on the stove. Lumbers grew up in the house where Cudjo lived most his life as a free man — originally a one-room log cabin, later expanded to four rooms.

Most of the descendants attended Union Missionary Baptist Church, which Cudjo and the other former slaves had founded in 1872 and named in honor of the soldiers who’d let Cudjo know he was free. There was also an extra home in the community called the “big house,” where any family could stay who’d fallen on hard times, Lumbers says. “It wasn’t really that big, but it had a big front yard,” where several times a year his cousins, aunts, and uncles would gather for a barbecue.

Africatown once had a main commercial district — including a grocery store, post office, nightclub, and hotel — but it was bulldozed in the early 1980s to build a highway. The middle school is in danger of shuttering owing to low enrollment.

The land that Cudjo and his fellow Africans bought from their former owners to build a settlement is now encircled by factories that locals believe have polluted the area, causing cancer and other illnesses. Last year, an Alabama law firm sued International Paper, which for many years had the largest footprint there, for releasing dangerous chemicals in violation of EPA rules.

Lumbers is returning to his birthplace after he retires next year. “I’m going to get that piece of land, near the church, and I’m going to build a family house. For all my kids” — he has six — “and my kids’ kids” — there are 21 — “and anybody that needs help. As long as you’re not doing drugs or acting a fool, you’ll be able to stay there until you get back on your feet. The big house. We’ll do it just like we used to.”

*This article appears in the April 30, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!