The 1971 film Klute, starring Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland, finds a new way to terrify me every time I watch it. The first in what is now known as director Alan J. Pakula’s “paranoia trilogy,” Klute is dark in all respects — set in a time when New York was abandoned by the federal government and besieged by blackouts, there’s both a lack of light and too many eyes in the shadows. Bree (Fonda) is being watched in her work as an actress and sex worker, and there are many scenes of her visiting her therapist to talk about her attachment to attention; she wants to be looked at on her own terms, even as the constant surveillance makes her want to disappear.

Bree can tell she’s being followed by a man whose presence we feel in every unlit corner of her apartment — we hear his footsteps on her roof and his breathing on her telephone. The apartment below her is occupied by Detective John Klute, played by Sutherland, who believes his missing friend is being framed for a series of murders that revolve around Bree, and that following her will lead him to the real killer. Early in the film we see Bree with a client, encouraging him to whisper what he wants in her ear and responding with a low, even, “I like your mind.” In Fonda’s performance, we can see that her skill is making men believe that everything she does was their idea. “Oh, inhibitions are so nice because they’re so nice to overcome,” we hear her say on a recording that plays over the film’s opening credits. But Bree doesn’t think of herself as being overcome by anything; she seduces and commands men in a way that they would never notice. Meanwhile, Bree notices everything.

Paranoia is often another word for instinct. What Bree senses is the need to protect and defend herself. At the same time she was filming the movie, so did Fonda. The decade in which Klute was made also was the time in which there were many other films and many other moments that mark a crucial turning point in Fonda’s life, and the prism through which we understand her today. She would later learn from the FBI files she got through the Freedom of Information Act that she had been the subject of a massive campaign to charge her with sedition. This is the label given to a person who “advises, counsels, urges, or in any manner causes or attempts to cause, insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty by any member of the military of naval forces of the United States,” a result of her famously vocal opposition to the Vietnam War. Her file was given the code name the “Gamma Series,” and in it, she found that her bank turned over her financial information without a subpoena, and the CIA had admitted to opening her mail (the first time the agency ever acknowledged doing so to an American citizen in the United States). There was a three-year targeted counterintelligence attempt to neutralize her impact and permanently damage both her personal and professional life, part of J. Edgar Hoover’s COINTELPRO operation to discredit and destabilize many different kinds of activists. Eventually, the FBI determined that she couldn’t be construed as actively undermining the government, with one informant reporting that she “did more listening than talking.”

The best actresses know that it is not enough to command attention — they also have to conduct it. Fonda was rated a threat by the government because she was a woman protected by every form of status and power available. By the time Nixon was requesting briefings on where she went and what she did or said, she was already a critically acclaimed and commercially successful actress, a white, wealthy, and beautiful woman who also happened to be the daughter of Henry Fonda, one of the most famous actors of his generation, a faithful icon of masculine Americana in film and theater. In the same way she knew how to hold the eye onscreen, she knew how to direct the attention she generated to people who were going unheard and unseen in real life.

This month, Metrograph is showing “Jane Fonda in the ’70s,” a series commemorating her most enduring achievements on and off film sets of the decade. It’s conceived by Melissa Anderson, the film editor at 4Columns and a frequent contributor to Artforum and Bookforum. Previously, Anderson was a film critic for the Village Voice, which was — full disclosure — where we first met a few years ago, when I was working as an editor. I interviewed Anderson at her Park Slope home about the series she pitched to Metrograph because, in her words, “any time is a great time to celebrate Jane Fonda.”

That’s true, and it’s also certainly not a celebration that has to be contained to retrospectives. Fonda still has a very active career — Book Club is currently in theaters, and it is as much of a delight as everyone says it is. Fonda was also at the Cannes and Sundance Film Festivals to promote an HBO documentary about her life, Jane Fonda in Five Acts, directed by Susan Lacy, which is scheduled to be released later this year. Anderson believes it’s necessary for viewers today to watch Fonda’s films from this time, while also considering what she calls Fonda’s extreme bravery: her commitment to the Black Panthers, the feminist movement, and most famously of all, her vocal opposition to the Vietnam War. The series includes narrative films such as Klute and 1978’s Coming Home, which Anderson says makes the perfect double bill, whether or not you can make it to Metrograph — they are the films for which Fonda won her two Best Actress Oscars, and it’s where Anderson says you can “see the full range of her acting, which is formidable, in two very political films playing at two very different registers.” (She also says Klute should be mandatory viewing for all New York City public school children, which I completely agree with.)

Fonda’s life is well-known for its narrative qualities, the acts and arcs easily recognizable and frequently recounted. There is the tragedy of her childhood, after her mother committed suicide when she was 11 years old; the years spent at boarding schools and Vassar, where she developed the eating disorders that defined most of her adult life; her time spent studying Method acting with Lee Strasberg, and her promising early career as an actress; her years in France, where she made Barbarella with her first husband, Roger Vadim. It was 1968, while Fonda was living in France with Vadim, when she attended her first antiwar rally. She didn’t like it. “It was all about how horrible America was,” Fonda explained to Hilton Als in a 2011 New Yorker profile. “I really believed that if we were fighting, there was a reason for it.” In her 2005 autobiography, My Life So Far, Fonda writes of the early months of her first pregnancy, when she was on bed rest. Up until then she hadn’t been watching the news, and barely understood where Vietnam was. “What attention I did give to it allowed me to remain comfortable in the belief that it was an acceptable cause,” she says of that time — in retrospect she realizes she thought women couldn’t change anything, except table settings or diapers — but could not go back after seeing images on French television of the damage American bombers were doing to Vietnamese schools, hospitals, and churches.

In the seven years between the release of Klute and Coming Home, Fonda solidified her status as someone J. Hoberman once called “the most politically outspoken star in Hollywood history.” Only two years after that first antiwar rally, Fonda had become so devoted to activism she told Ken Cockrel, a Detroit-based lawyer, activist, and member of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, that she was considering leaving acting entirely. He told her that there were enough activists already; what they needed was a movie star.

And so Fonda made movies — and speeches. In July 1972, Fonda traveled to North Vietnam to tour the dike system protecting more than 15 million Vietnamese people from flooding, and which the American military had targeted for bombing (an obligatory aside to say that the American government has always denied this). She made radio announcements asking American soldiers to remember their humanity and protest the war any way they could. Photos of her sitting and smiling inside an anti-aircraft gun used to shoot at American planes, however, was what led to one threat of assassination for betraying her country, and a formal statement from State Department spokesman at the time, Charles W. Bray, who called her actions “distressing.” Other people called it treason.

Fonda has apologized for the photo repeatedly, and will be doing penance for it perhaps forever — “Hanoi Jane” is a nickname like a flashbulb memory, one that easily encapsulates a chaotic time — but she has always denied that she has to apologize for any other work she did in Vietnam, reminding us that the government was lying to American soldiers, and it was not traitorous to protest the war.

It was also during the filming of Klute that she met Howard Levy, an Army doctor famous among GIs for serving prison time after he refused to train special forces going to Vietnam. He pitched her and Sutherland on an “antiwar alternative to Bob Hope’s traditional pro-war entertainment,” and they loved the idea. Their first three performances were at the Haymarket Square coffeehouse near Fort Bragg in North Carolina, which went on despite police outside taking photos of soldiers who attended, and even going so far as calling in a fake bomb scare, which the performers just ignored. F.T.A., the documentary included in the Metrograph series, is an account of that political vaudeville show which Fonda toured for G.I.s stationed on their way to or from Vietnam, together with Donald Sutherland, singer Holly Near, poet Pamela Donegan, actor Michael Alaimo, singer Len Chandler, singer Rita Martinson, and comedian Paul Mooney. It was attended by an estimated 64,000 soldiers, sailors, marines, and members of the Air Force, and bootleg recordings were sold among soldiers who couldn’t attend.

In 1973, Fonda spoke at a rally with the Vietnam veteran Ron Kovic, who was paralyzed from the waist down in Vietnam, and who would be portrayed by Tom Cruise in Born on the Fourth of July, the film based on Kovic’s autobiography. At that rally, Kovic said, “I may have lost my body, but I’ve gained my mind.” Fonda began to wonder if a film could be based around that sentence, something about “two men and the transformation and salvation of one of them,” insisting that Nancy Down be hired as the screenwriter to ensure a “woman’s perspective.” The resulting film was Coming Home, which was released toward the end of that decade and co-starred Bruce Dern as Fonda’s husband who is sent to Vietnam, and Jon Voight as a soldier paralyzed and recovering in the veteran’s hospital where Fonda’s character volunteers.

Fonda married her second husband, Tom Hayden, that same year. He was a working-class radical, and in her memoir she writes that his ideas were part of what drew her to him: “I know, it sounds so seventies — falling in love because of a political slide show.” Hayden didn’t think that Coming Home went far enough in its politics, but Fonda has quoted the playwright David Hare — “The best place to be radical is at the center”— when she talks about her decision to make the film centered around a love triangle between three people who are dealing with the trauma of the Vietnam War on an immediate, personal level. “I wanted to make films that were stylistically mainstream, films Middle America could relate to: about ordinary people going through personal transformation.”

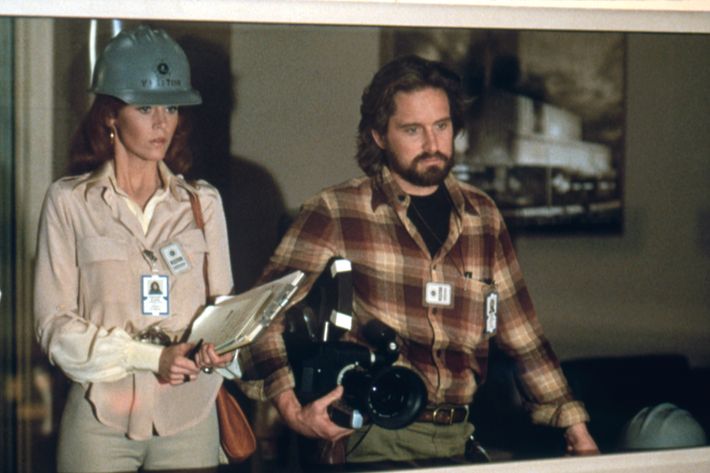

As a series, viewers can clearly see that the films chosen are accessible, enjoyable, and explicitly political — that one element does not override the other. There is Julia, the Lillian Hellman biopic that was almost definitely fabricated by its author, but the simple, devastating story of Hellman’s relationship with Julia (played by Vanessa Redgrave), a medical student turned anti-fascist who was murdered by Nazis as Hitler took over Germany. As Hellman, Fonda’s tense anxiety is at odds with her willful determination to help her childhood friend, Julia, a woman whose bravery does not exclude the fear she feels. There is also The China Syndrome, which has an eerie real-life parallel: On March 16, 1979, The China Syndrome was released, co-produced by Fonda’s production company and her co-star Michael Douglas, a film they wanted to make to call attention to the crisis of nuclear power. Fonda plays a journalist who wants to do more than puff pieces on singing telegrams and birthday parties at the zoo; Douglas is her cameraman who doesn’t play by the rules. Together they accidentally witness an accident at a nuclear power plant, and uncover a conspiracy to keep it quiet so that business can continue as usual.

On March 18, 1979, the New York Times published an article featuring nuclear experts calling the film a “character assassination” of their work, technically flawed and total fiction. On March 28, 1979, the country’s worst nuclear accident and nearest nuclear disaster occurred in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. Known as Three Mile Island, the events of the real-life reactor malfunction so closely paralleled the fictional events of Fonda’s film that it was hard to know if The China Syndrome was another example of Fonda’s acute intelligence for making films with such contemporary parallels they were almost occurring in real time, or if it was witchcraft. In any case, everyone went to go see the movie. Her collaboration with Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin, Tout Va Bien, will play with an introduction from the writer and critic Tobi Haslett, who told me over email that it is Fonda’s “dalliance with radicalism, her willingness to offer herself up as the beautiful face of insurrection” that continues to fascinate him. In Bien, he explains, the film is driven by the inherent tension in what is the filmmakers’ “single, agonizing preoccupation: the role of intellectuals in the revolution. Godard and Gorin, as good Marxists and producers of ‘culture,’ are like Fonda’s character, and Fonda herself: cleaved from the proper agents of revolt, but moved, from a prestigious distance, by their own sympathy and rage.”

When I ask Anderson if there can be a comparison made between Fonda’s work then and the work of actresses today, she states the obvious: “All of this was happening before social media. Before email.” There is no way to gauge what would have happened if that photo of Fonda in Vietnam had been tweeted and she would have been compelled to give an instantaneous response. Anderson points out that Cynthia Nixon recently gave what is widely considered to be the best performance of her long and accomplished career as an actress when she portrayed Emily Dickinson in A Quiet Passion, and we briefly discussed how you could draw a tenuous connection between the way Nixon is now transitioning from being known as an actress first and activist second to a full-fledged political career. Yet “what even constitutes a political statement these days,” Anderson reminds me, “is so vastly different from what it was then.”

There’s a reason we’re distrustful of celebrities who use their fame as a platform for political causes: Our paranoia may be cynicism, but we’ve been burned before. There is (sometimes!) an inverse relationship between enthusiasm and understanding, and not always, but often people early to a cause have more opinions than thoughts. For example, there are many actors and actresses who support harmful and inaccurate policies against sex work. Most recently, the pop star Grimes has been criticized for seemingly supporting her boyfriend’s belief that unions are normally fine, just not at his car factory. Awards shows have increasingly become a platform for political statements that are often either hollow or at least perfunctory. We can allow an actor their tendency toward performance, but to make activism performative requires a suspension of disbelief that we, the audience, cannot in good conscience give. “Unbearable sanctimony and absolutely toothless stances,” is how Anderson sums it up.

Fonda has written of her regrets, which are not limited to the photograph, saying that in retrospect she should have talked less and listened more, rather than speaking “all the time, everywhere, on and on and on in a frantic voice tinged with the Ivy League … In interviews I was humorless, talking too fast, in a voice that came from some elitist, out-in-space place, anger seething just below the surface. This was when I began to use radical jargon that rang shrill and false.” And yet her acceptance speech for Best Actress in Klute is, even today, a testament to her ability to read the room. Knowing that everyone present would be on edge about what she might do or say, and on the advice of her father, she chose, instead, to simply say that there was a lot to talk about, but that tonight was not the time. She thanked the Academy for their recognition, and left the stage.

More than that, in Patricia Bosworth’s biography, she says that Fonda once told Vivian Nathan (the actress that played her therapist in Klute) she believed her activism had made her acting better; she has also used the principles of movie stardom as an activist. In the decades since, Fonda’s film career has always included choices aligned with her beliefs, showing that she kept listening and learning as she worked. The 1980 film 9 to 5 came came from Fonda’s friendship with Karen Nussbaum, a fellow antiwar protester who founded 9to5, a national clerical workers organization that would become the Service Employees International Union known as Distric 925. The Jane Fonda Workout, the VHS tapes that would become the second-most famous part of her personality, were done in large part to finance Hayden’s political campaigns. Even in her 15-year retirement from film and over the course of her marriage to Ted Turner — which is a wildly contradictory part of her third act in our public imagination — she was always working, traveling, and learning not just to be better but to do better.

Other actresses with similar politics and similar government attention did not survive, like Jean Seberg, a member of the Black Panthers who was targeted by the head of the Los Angeles COINTELPRO division. They planted stories in the Los Angeles Times and Newsweek while she was pregnant, accusing her of cheating on her husband and alleging that her baby was fathered by another Black Panther member. The stress of the accusation caused her to attempt suicide, and she survived but miscarried. For nine years she attempted suicide every year on the anniversary of the miscarriage, until September 1979, when she did finally kill herself. That same month the FBI admitted they had fabricated the story, and her husband killed himself several months later. Less tragically — or to be more accurate, tragically in a different way — when Fonda first went to France to make movies, the press called her la B.B. Américaine, comparing her as the American Brigitte Bardot; Bardot is now a hateful bigot, and has been charged with inciting racial hatred against Muslims five times.

“How do you reconcile the celebrity with the committed citizen?” Anderson asks. “Undoubtedly, undisputedly, Jane Fonda did a lot of courageous work. Was she able to do that because of who she was? Because of her fame in another realm? And, as a public speaker, as someone who went to meet many different types of people, how much did she deploy her skills as a trained thespian to help advance her cause? It may be filled with contradictions that are irreconcilable, but if we look at her record as a public citizen, I think it’s quite impressive.” There are many ways women in the public eye can lose themselves, and far fewer examples of women who have been fallible and survived. It is not that Fonda provides a model for other actresses that can also be a metric, but that she has made for more possibilities. I like her mind.