Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible.

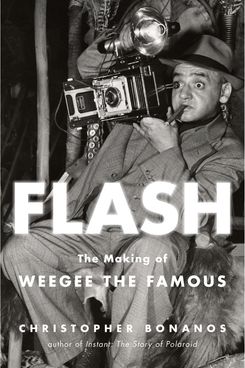

Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous, by Christopher Bonanos (Henry Holt, June 5)

The writer of this definitive, rich, and clever biography of the iconic urban street photographer happens to be New York’s city editor. But in the words of Reading Rainbow’s LeVar Burton, you don’t have to take my word for it: Bonanos has earned universal raves for his account of the ascension of a shtetl boy (né Usher Fellig) to the status of self-made legend — on the strength of not only his uncanny ability to get to the scene of a crime almost before it happened, but also on a genius for mirroring back to us our own seedy voyeurism.

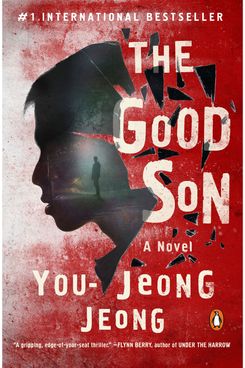

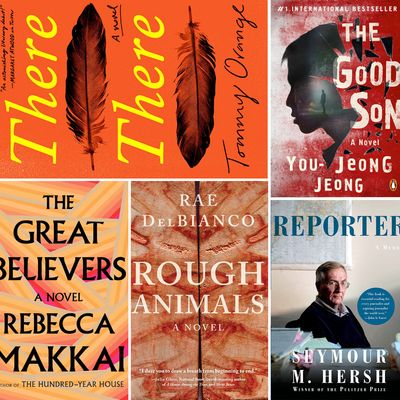

The Good Son, by You-Jeong Jeong (Penguin, June 5)

Jeong’s thrillers are wildly popular in South Korea, and we’ll soon learn why. Her first book published in English enters the mind of Han Yu-Jin, a seizure-prone youth who wakes to discover that he might have just murdered his mother with a straight razor — or not? In Han’s highly unreliable narration, the discovery of the culprit is only a stop on the way to the real revelation, the unfolding of his family’s warped dynamic. The gore is intense, but the psychological terror might never wash off.

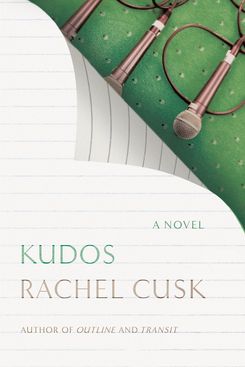

Kudos, by Rachel Cusk (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, June 5)

Cusk’s masterful trilogy puts her in the running for queen of autofiction (novels with self-consciously autobiographical narrators). Her triptych began with Outline’s unnamed writer, teaching a summer seminar in Greece. Transit gave her a name (Faye) along with two kids and a half-built London house. Kudos finds her remarried but disenchanted as ever, and sends her across Europe to survey a bankrupt literary world and a continent whose center isn’t holding. Faye is both a compelling voice and (in contrast to most male autofiction) an attentive listener to others, who are forever telling their stories.

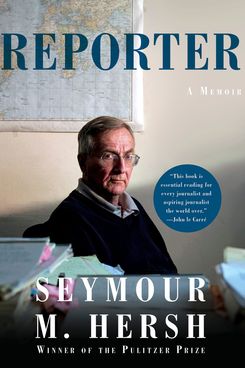

Reporter: A Memoir, by Seymour Hersh (Knopf, June 5)

It’s hard to believe that the same reporter who exposed the My Lai massacre in Vietnam informed us, 36 years later, of systematic torture at Abu Ghraib. Even more impressive are all the exposés of nefarious foreign misadventures in between and since, which make Hersh’s career an essential and lengthy footnote in the history of American human-rights abuses. From LBJ to Kissinger to the “ass-kissing coterie of moronic editors” at the New York Times, no one comes through unscathed, including the controversial journalist himself.

Rough Animals, by Rae DelBianco (Arcade, June 5)

Invoking Cormac McCarthy in praise of a brutal but beautifully written Western is a cliché impossible to avoid (and no critic has) when it comes to this enrapturing debut novel. Twin orphans Wyatt and Lucy are barely surviving on a family cattle ranch in the Utah desert when a well-armed feral 14-year-old girl ambushes them, killing four animals. Wyatt gives chase through an unforgiving landscape full of hungry coyotes, meth dealers, and armed gangs. Meanwhile, flashbacks bring the tragedy that took his and Lucy’s parents — and led to the present pass — into horrifying focus.

There There, by Tommy Orange (Knopf, June 5)

Among the survivors of our founding atrocity — the decimation of the Native Americans — the majority live not on reservations but in urban centers, and many occupy a state of half-assimilation, a place Orange’s well-drawn characters call home. In linked stories, a wide array of Natives struggle with common American crises (alcoholism, unemployment, depression) as well as those specific to a systematically buried identity. They reassess their prospects and their heritage in the run-up to a culminating event, the Big Oakland Powwow, where disaster strikes in a dramatic and satisfying conclusion.

Fight No More, by Lydia Millet (Norton, June 12)

In linked stories set among Los Angeles house-hunters that bring to mind the high satire and intricate structure of Robert Altman’s Short Cuts (itself based on Raymond Carver stories), Millet uses a real-estate agent’s appointment-book as a prompt for pieces on unsettling characters: a sex worker—au pair and her abusive stepfather; a rebellious, spoiled teenager; a famous musician prone to dramatic suicide attempts; a woman who thinks she’s the victim of “handyman midgets.” Millet herself is a shape-shifter, moving from suspense to comedy to absurdism between novels and, now, between chapters.

The Great Believers, by Rebecca Makkai (Viking, June 19)

Makkai was already a rising star, but this third novel has been talked about for months. She takes up a theme seen in recent novels like Tim Murphy’s Christodora — the trauma inflicted by AIDS on the loved ones who survived the epidemic. Two distinct narratives intertwine ingeniously: First, a Chicago art dealer’s life derails in the ’80s as the disease takes everyone around him; second, 30 years later, the sister of his first friend to die searches for her grown daughter in Paris. The two roads converge in the end, to heartbreaking effect.