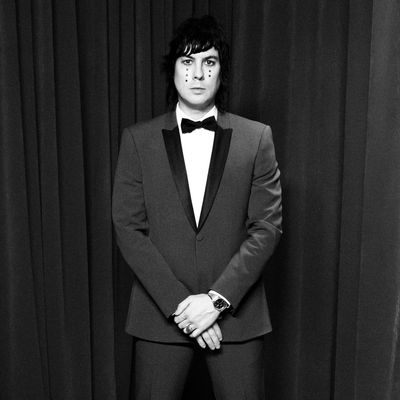

Even if you don’t know Johnny Jewel by name, chances are you’ve heard his music before. As the driving force behind the experimental electronic group Chromatics and the disco provocateurs Glass Candy, Jewel has long attracted a cult acclaim for the way that he harnesses emotive sounds (it’s no wonder David Lynch tapped Chromatics as one of the bands to perform at the Roadhouse in Twin Peaks: The Return). His musical work has been so instrumental that it’s reshaped the visual language of film, too, particularly in 2011’s Drive. The Los Angeles–based Jewel also heads up the prolific label Italians Do It Better, which operates with a feverish DIY spirit down from the artist’s artwork to its many releases by the likes of Nite Jewel, Desire, and Farah.

Chromatics, perhaps the most well-known of Jewel’s projects, makes music whose darkness shines as clearly as the disco ball’s reflections do, especially on albums such as Kill for Love and Night Drive. Today, Chromatics released a shimmering, self-directed video for “Blue Girl,” a new single from the band’s forthcoming album Dear Tommy. Jewel says the idea for the video — which is replete with symbolism, from roses to candles — came about when he was in the desert, and he thought about experimenting with optical illusions in a mirror. Through a technique called Pepper’s Ghost (the same one used in Disney’s The Haunted Mansion), the band “created this sensation of vision, this presence” to explore ideas of past, present, and future, among other things.

Jewel spoke with Vulture about the new video, astrology, how limitations help artists, discovering John Cage through Fantasy Island and, yes, how their long-anticipated next album Dear Tommy is coming along (and hopefully being released this fall).

How are you? What’s going on Chromatics world these days?We just released a video for “Black Walls” a couple of weeks ago, letting everyone know that Tommy’s on the horizon once again. The last thing we had released from the record was “Shadow,” and I generally like to have counterbalance in our singles. I wanted to release a single that was a little more oblique. And then this one that we’re going to release is more in the vein of “Cherry” or “Shadow.” So it’s kind of what we’ve been up to, while recording and mixing like crazy. Making a bunch of art. We never stop, so it’s interesting. When we do make a public statement the feeling is, “what’s the band up to,” you know? The schedule is all day, every day.

What headspace were you in when you were writing and recording “Blue Girl”?

The headspace of the song is basically a dialogue between you and yourself. And the “blue girl” is speaking to the part of yourself that only you know. Your inner world. It’s kind of like the public you and the private you having a conversation, and bouncing ideas back and forth. The part in my case, specifically, is the hermit talking to the extrovert or the more public person. My natural tendency is to completely remain in solitude or in private, doing our thing without anybody seeing it or hearing it.

Inevitably that involves contending with the extroverted part of yourself, too.

Yeah. I mean, I’m a Gemini. Adam [Miller] from Chromatics’ birthday is today, he’s also a Gemini. He and I wrote the lyrics together, so there’s a duality between us as a writing team. And then also with ourselves as being two-headed. All these things are sort of touched on in the lyrics, in how we deal with ourselves and each other.

In the video, we’re also playing with the idea of the undead. Talking to other side and through the mirror. The idea of the musical bridge, when we’re all dressed in white, is when we’re in purgatory, or in an afterlife. It’s fun, it’s candy; but these are the concepts that we’re playing with. The Geminis in the band are the ones with the white eyes, so me and Adam.

Are there any Gemini traits that you particularly identify with?

The extreme polarity, in terms of feeling hot and cold. Feeling really, really, strongly and then simultaneously being able to feel the other way. There’s a lot of opposites in things that we do. For me it’s more about human nature, things like that. I’m not an astrology expert or anything.

When we last spoke a few years ago, you said that Dear Tommy was about someone who comes into your life, tells you something about yourself, and leaves. I know that a lot has changed since you first announced the album, but I’m wondering if that core has shifted.

Oh, not at all. It’s stronger than ever. And that was part of the reason why I was trying to find my footing with it. The apple on the cover represents a lot of things, like our lyrics. But one of the things it represents is knowledge. I think in the Bible it’s possibly more like a pomegranate, but in our culture now we refer to it as an apple. There’s an alternate meaning of a poisonous apple, like in fairy tales. And also the poison of knowledge, and how someone giving you that isn’t good for you. And that can take you years to deprogram.

For me, the apple is a very interesting symbol of this kind of idea: Someone coming in and exiting, usually through death. In my case, the album is about two people, that’s my own personal point that I’m drawing from. And they both exited in automobiles. In the Dear Tommy video, it’s shot from the vantage point of a windshield and trying to reach through the other side. These things, for me, are how to process loss. Everyone has these people. Every one of us in the band has their own Tommys.

What’s the dynamic like between you and Ruth [Radelet], particularly as she’s often singing about experiences you’ve written about and had?

Well, we try to keep everything between the lines and abstract enough to where anyone can relate, depending on their given mood or what they take away from it. Things have usually two to three different meanings or entendres. So within that she’s able to find her inspiration. We’ve been working together for so long, and Ruth and I lived together for eight years. Everything is so second nature that when we’re recording and putting together songs, it’s more like everyone is working on a puzzle and finding pieces on their own.

Beforehand we talk about concepts, about ideas and feelings we want to represent. Adam and I will record demos of ourselves singing to document ideas, but usually we don’t record with Ruth until it’s time to pull the trigger. She’s still essentially exploring the song, and this intimacy is really key to the feel of Chromatics. So we never rehearse. The actual vocal recording is way more similar to capturing film or something. You’re just collecting raw power and performance. She she doesn’t even wear headphones; we record with the music playing in the room. It’s very, in some ways, unprofessional or untraditional.

We try not to overthink the vocal aspect of it because to me the voice is … it’s so precious in music. And out of how many billions of people on the planet, the ability to pick out a human voice and recognize that that’s a specific singer regardless of post-production treatments or fidelities or how it’s being broadcast, whether it’s a radio or a nice sound system or in a cinema house? That’s a very human thing. And we always are striving for the best we can do, but I believe it’s very important to have that raw edge to the vocal. And I think it’s one of the things people love so much about Ruth.

How did that happen?

We had lived together for six years before we ever recorded anything. And it was Adam’s idea to have her sing on the chorus of “In the City.” So the very first time she sang it was under these circumstances: very casual, she was holding the mic and there’s music coming out of the speaker on top of the piano. And it worked. So we kept doing it that way.

I’m kind of superstitious in this way. “Blue Girl” was recorded with the same bass that I recorded for “Cherry.” Which was the same bass for Night Drive. We shot the “Blue Girl” video last night, and actually when I was recording, one of the strings broke. We’ve had the same strings for over a decade. So we shot the video with the broken string, just because we leave things how they are.

Does superstition seep into other parts of your life, too?

I try not to put too much weight on it, but I certainly have strong preferences. I have an 8-year-old daughter and I think about this sort of stuff now more than in the past, because when I was doing things for myself I had my own preferences for what I didn’t want to do. I look at it more like, it’s useful for an artist to have parameters to work with. Limitation is good, and as I spend more and more time on earth thinking about things, what I used to feel as superstitions are more so self-imposed parameters in order to be productive. Having limitations is key for an artist.

How have self-imposed limitations factored into the upcoming Dear Tommy release, if at all?

I kind of am tightening the grip on myself. Giving myself more distinct walls in order to focus on what this particular album is instead of every single artistic statement I want to make in my life. Which is the nature of starting on a macro scale, and coming closer into focus and more and more micro, more and more succinct, boiled down, direct. I think earlier on I was trying to put every possible idea I had into one record, and as I’ve tightened that grip, the ideas are actually multiplying. Which is just a testament to what I’m saying about how powerful limitation can be. We’re at a place where we originally had a 17-track record, and now even as I talk to you, I have no idea how many tracks it’s going to be. It’s most likely going to be more than 20, but I really don’t know. It’s a complete explosion right now.

At the same time, it’s sometimes hard to know when to stop picking away at something you’re working on. Especially since Chromatics songs are such amorphous entities.

Oh, of course. This is one of my rules that I make for myself. I don’t overwork it. It’s more about, is it good and does it represent the life force of the idea? Or does it get in the way of the idea and it’s a rendition of an idea? Me, I don’t look for perfection. People often say I’m a perfectionist because I work a lot. And I’m not a perfectionist at all. I just have to have that moment when I’m ready to pull the trigger. That moment can be really sloppy, really bloody or it can be really pristine or minimal. It can be two minutes, it can be 16 minutes. There’s no real benchmark I’m aiming for, other than the feeling that first sparked the song has to be intact.

Your song “Windswept” ended up being a pretty central part of Twin Peaks: The Return. I read that it was named after the street you were born on in Houston?

I was born in the Heights, but that’s the house we lived in when I was born.

Did having that song featured on the show feel like coming home, in a way?

It didn’t feel like coming home. Ever since I left Texas I feel like I’ve been floating in outer space. Texas still feels like home: the weather and the grass, and the smell when the rain hits the oil on the pavement. Those moments are burned into my psyche so deeply that everywhere else feels like I’m in transition.

What was crazy was that I first watched Twin Peaks in Houston, and the very first time I watched it … our neighbor had shot himself with a rifle. I heard the cracking sound, and I was like, “Okay, that’s odd.” I didn’t really know what it was. And then as [my then-girlfriend Heather and I] were watching the pilot at my mom’s house, there were police sirens in the show. I remember police sirens being projected onto the wood paneling. And it took me a while to realize that it was coming from the outside, and someone knocked on the door and it was the police. Basically, the guy shot himself and then went kind of crawling up to our doorway. And then because of that, the police were all outside the house trying to figure out if there was somebody in my house that had done this.

Whoa. I’m sorry to hear that. How old were you when this happened?

I would have been 16 or 17. It was confusing. It wasn’t scary, it was just really, really strange.

So I started off my relationship with Twin Peaks in my mother’s house with this sort of eerie set of circumstances. I had seen Eraserhead, I had seen Elephant Man. Doing “Windswept” wasn’t really a reference to that. It was more about this dream I was having about leaves blowing around in this negative black space. “Windswept” is like a beginning of my first house. But it’s one of those classic slow jazz kind of titles. So I got really into that idea, and then of course not having any clue that it would be used in the show. But Twin Peaks is something I visited and revisited throughout the course of my life at different times.

Recently you released Themes for Television, which includes music originally meant for Twin Peaks. What television themes were important to you as a young person?

I really love soap opera music: The Young and the Restless, Days of Our Lives, Guiding Light. Very melodramatic, foreboding scores with that hovering, omnipresent stress. Or fatalistic romance. I’m not a scholar of anything in particular, I definitely have distinct memories. The more horrific tones of Fantasy Island, when things would turn dark. It’s similar to The Twilight Zone, which I also love. When people would get what they want, then it would have this strange twist. Usually rooted in some ego lesson.

I saw more television than films for sure as a kid. As an adult, it’s interesting to see where film scores, and TV scores, are pulling from modernist composers like John Cage, and Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Penderecki, and stuff like that. I guess I don’t know the history of it, but there’s a shift that happened in sci-fi in the ’50s where things started becoming less Hollywood orchestra and more experimental. Those gestures … that was my first introduction to experimental sound. You know the Rothko Chapel?

I do.

Have you heard the piece Morton Feldman did for the induction?

I haven’t.

It’s amazing. If you’re into that kind of stuff you should see it. It’s interesting how things are handed down or transferred down. People ask a lot of times If I find it strange to see mainstream taking bits and pieces from the underground. Or is it frustrating? It’s easy to take the stance of that as a negative thing. You could look at it from another perspective, which is that they’re opening what you do to the palate of the mainstream. Drive is the perfect example. All the pop singles in Drive already existed, they had been out for a while. There was no way the mainstream was ready for that when those songs came. I think that ultimately if you’re in it for the long game, that relationship between the underground and above ground can be beneficial in terms of introducing ideas to a larger audience while you slowly pierce through that. But music is a language, culture is a language that’s passed around.

If you told John Cage, “Oh hey, this guy likes you, but he first heard stuff like this on Fantasy Island?” I don’t know if he’d be that excited [laughs], but it made an impression on me and it planted a seed that got me interested to discover those types of things later. The conversation is always changing and shifting, but for a long time there was this idea that film is superior to TV. I don’t make those kinds of judgments. For me, everything is an extension of whoever’s doing it.

This interview has been edited and condensed.