Amanda Fucking Palmer is sitting before a gilt-framed mirror in a dressing room at the Ford Amphitheater on Coney Island, naked except for some grey undies. Spandex-clad handmaidens rub lotion on her arms, while a stylist affixes a silver crown adorned with black jewels to her curls. “It feels like it will stay, but can you make it more viney-windy?” she asks, pulling a short curl, spray-painted green for the occasion, out of its binding. A Periscope video of the singer and performance artist’s partial transformation into the Queen of the Coney Island Mermaid Parade had concluded just before Palmer stripped down (Periscope frowns on nudity, one of Palmer’s preferred states), during which a viewer asked about the difference between a siren and a mermaid. “Maybe we need to get Neil Gaiman in for a brief discussion on the history of mermaids and folklore,” she says. She applies a coat of turquoise lipstick and threw on a Cockney accent: “Oi! Gaiman! What do you know about actual mermaids?”

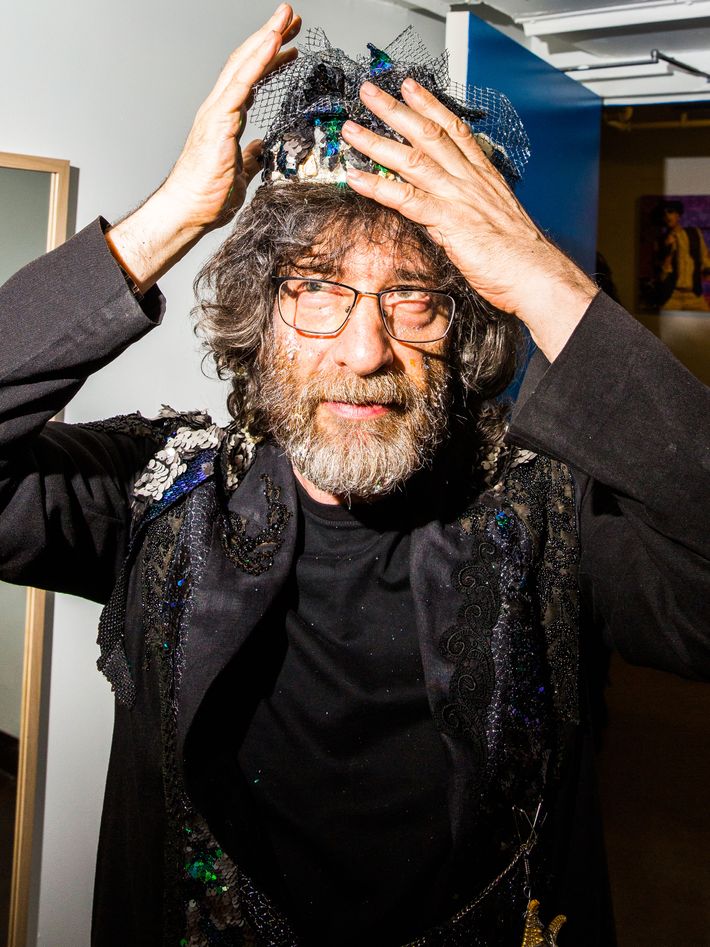

Palmer’s husband, the acclaimed British fantasy author and resident mythology expert, is in the room next door, getting dressed as King Neptune. “My glitter is shedding everywhere,” he says when I knock on the door. His usual look, black jeans and a black jacket, is only slightly modified for the occasion — one of his favorite designers, the goth-Victorian couturier Kambriel, has sewn silver and green and black beads and shells (and a starfish) to a linen jacket she’d made him a few years ago. His face, framed by a heavy mop of silvery curls, is dusted in glitter. He’d also grown his beard out. “When I learned that I was going to be a mermaid king, the first thing I had to do was grow a very serious ‘Fuck off’ beard because if you don’t have a beard, then no one would know you are Neptune,” he explains. “I’ve seen pictures of Neptune, and there are none in which he is clean-shaven. It’s not a thing.”

The Mermaid Parade, founded in 1983, is a peculiar New York institution, a celebration of bohemian nonconformity featuring homemade floats and costumes heavy on fish puns (The Wu Tang Clam Ain’t Nuthin to Shuck With, The Salmon Witch Trials, The Ruth Wader Finsburgs…). It seems fitting that Gaiman and Palmer would preside over this proud collection of freaks and renegades, given that they’ve unofficially ruled as weirdo royalty for years. Palmer, who is perhaps best known as the lead singer and pianist of the punk-cabaret duo the Dresden Dolls, writes raw, confessional lyrics about subjects as varied as Harvey Weinstein, the dark humor of abortion, and her deep love for Judy Blume. Gaiman’s prolific collection of books, short stories, and graphic novels explore more ethereal realms: In his best-selling novel, American Gods, which was adapted for TV last year, Gaiman raises the question of what happens to deities when humans stop worshipping them. What did he think Neptune was up to today? “Probably homeless at the edge of the sea,” Gaiman says, after a moment of consideration. “Kind of diseased, talking about his glory days.” Still, Neptune isn’t completely forgotten. “Sailors still have little rituals,” he points out. “I think he may get a little bit more worship than a lot of gods.”

Gaiman was supposed to be in the U.K to fill his postproduction duties as showrunner for an upcoming Amazon mini-series, adapted from his first novel, Good Omens (co-written with the late Terry Pratchett), but the invitation to Coney Island had been too tempting to turn down. “I’ve wanted to go to the Mermaid Parade ever since I heard that it existed. There’s something very inclusive about a mermaid parade,” he muses. “You’re a mermaid if you say you are.”

A royal attendant, dressed in sparkly hot pants and a purple sequined bra, arrives with Gaiman’s crown (black netting with feathery iridescent accents), which had been slightly crushed on the trip out to Coney Island. “It was like a crown, and now it looks like a little old lady’s hat,” Gaiman says sadly. He attempts to restore its shape, tentatively puts it on, and surveys himself in the mirror. “Given that I’ll be sitting next to Amanda, no one is going to be looking, anyway.”

Gaiman — whose dreaminess is so well-established that the fantasy website Tor.com published a humor piece titled “Fiction World Rocked As Woman Claims No Sexual Attraction to Neil Gaiman” — is perhaps selling himself short. Palmer and Gaiman met in 2008, when she asked him to write stories to accompany photographs of herself posing as a corpse. They were married in the home of the authors Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman. They were each cult-famous before they wed, but their marriage seems to have multiplied the effect. On her blog, Palmer helps build this mystique, sometimes writing about their sex life (“waking up with neil,” she wrote in 2013, “i want to crawl inside his mouth and go back to sleep inside his lungs”). They currently have what Gaiman has described as a “theoretically open relationship.” “It’s kind of closed in practice,” he told the U.K. Times in 2017. “Neither of us is going to sleep with other people when we’ve got a two-year-old with us.”

At the amphitheater, they imagine a first encounter between the characters they’re playing at the parade. “We met at Whole Foods,” says Palmer, who, while far from conventional, is the more earthbound of the two. “I disagree completely,” says Gaiman, leaning over to zip up the back of her scaly aqua hot pants. “I think she was doing the usual Amanda thing, sitting on a rock somewhere luring sailors to their deaths by singing to them with a ukulele, and I happened to wander by. I was lured. Lured to my doom.”

As Palmer puts on a bedazzled bra and ties a foamy bustle around her waist, Gaiman ponders the timeless appeal of the sea. “There is something so elegant and sleek about the water,” he says. “And the idea of merpeople has always been beautiful. It reflects an idea that the sea is a reflection of the land and the land is a reflection of the sea.” Lately, he adds, the waters below have been threatened by the habits of the creatures up on land. “We’re approaching a place right now where there may soon actually be more plastic in the sea, pound for pound, than there are fish. That’s fucked up.” The parade, he says, is a way “to raise awareness of our guardianship of the sea, of the fact that the seas and the oceans belong to humanity, but we came from them and …”

“We’re just fucking tourists, trashing the joint!” Palmer cuts in, with the sort of lusty enthusiasm that fans of the Dresden Dolls would find familiar. “Exactly,” Gaiman replies. He turns to gaze at his wife, who looks like she could have stepped out of a Waterworld remake directed by Tim Burton. “I like everything,” he says, “except the hair with the crown right now feels very sort of high-school beauty queen.”

She glances in the mirror, then removes the crown. “Having Neil Gaiman as my personal stylist is one of the best decisions I’ve made in my life,” she says. “No one knows that he’s the magic behind the mystery.”

Back in her own dressing room, Palmer puts the final touches on her outfit: a broad-feathered collar, fingerless sequin gloves, a pair of thick, round sunglasses. Gaiman studies the phrase “Mermaid Power” drawn on Palmer’s chest in black marker. “I think that we could probably use mermaids to replace coal,” he begins. “On the other hand, the captive mermaids …”

“You look beautiful,” Palmer interrupts.

“I always look like this,” says Gaiman, who looks as dark and mysterious as his most famous creation, Dream, the star of the Sandman series of graphic novels, which Gaiman began writing when he was in his 20s. “You just have to look at me with fresh eyes.” says Gaiman, now 57. (Palmer is 42.) “This is the true person you married.”

Their 2-and-a-half-year-old son, Ash, climbs up on the couch beside his father. “Let’s at least give you some beads,” Gaiman tells him. “If you’re going to be a mer-creature, let’s have some green beads. And some blue beads.” He slings a few strands around Ash’s neck. “There. You look like a small sea prince in his pajamas.”

The royal family and their glittering entourage winds their way out of the amphitheater, down into the blazing sunshine, where a wicker rickshaw pushed by two green sea creatures awaits. They climb in, and the sea prince settles into his father’s lap as the rickshaw turns up Surf Avenue. “You look fucking fabulous!” a parade attendee dressed like an orange sea urchin shouts. Someone with very realistic gills thrusts a copy of Sandman out for Gaiman to sign; a person wearing a shark’s head pours a handful of green glitter into his palm. Palmer blows a kiss to the crowd, then hops off the rickshaw and, ukulele in hand, shimmies up to a troupe of dancing mermaids, her bustle bouncing behind her, the girls in mermaid tails drawn toward her like the tide coming in.

Down by the beach, Dick Zigun, the unofficial mayor of Coney Island and the founder of the Mermaid Parade, hands them a pair of giant scissors and asks them to cut four ribbons, one for each season, a ritual to ensure good weather and fun as the beach opens for summer. “So perishes winter!” shouts Gaiman as he does the honors. Palmer pulls off her Converse, her fishnets, her sparkly hot pants, her bustle, and last of all, the bedazzled bra, until she is once again naked except for a pair of grey undies. To whistles and cheers and whoops, she dives into the ocean. Gaiman removes only his shiny black boots and beaded jacket and walks in after her. A line of beautiful young women wade in toward the author to pay their respects (and ask for selfies). When the last photo has been taken, he turns to me. “I will say, I’m impressed by your commitment to journalism,” Gaiman says, indicating the waves creeping up around my waist. He slings an arm around my shoulder and gestures toward the beach. “Look at that,” he says. “Isn’t that wonderful? The costumes. And the drums. And the magic. And the idea that there are people who just came down to be at the seaside, and suddenly, a day at the beach turned into something completely unimaginable.”