If you know anything about Terrace House, you know it’s a very nice show about very nice people. The Japanese reality series, which streams on Netflix, follows six people living in the eponymous house who largely treat each other with kindness and respect, all while working to further each other’s shared dreams (and maybe even find romance along the way). When there is conflict — as in the infamous “meat crime” of Terrace House: Boys and Girls in the City — it comes from genuine disagreement, which makes the ensuing tension even more potent. But the current season, Opening New Doors, which premiered its second batch of episodes in late May, offers something a little unusual: an actual villain.

When Yuudai Arai is first introduced, the 19-year-old aspiring chef appears to be an exciting Terrace House prospect. In his very first episode, he reveals to the other two boys in the house that he keeps two stuffed pandas by his bed so he can always be surrounded by cuteness. He seems a bit awkward, but who isn’t — especially when they’re on a reality-television show looking for love? Soon enough, however, Yuudai admits that he simply wants to date someone who’ll take care of him. When someone joins Terrace House, they usually discuss their “type” in terms that are rarely physical — someone who will help me pursue my dreams, someone who will make me laugh, someone who is easy to talk to. Not so for Yuudai.

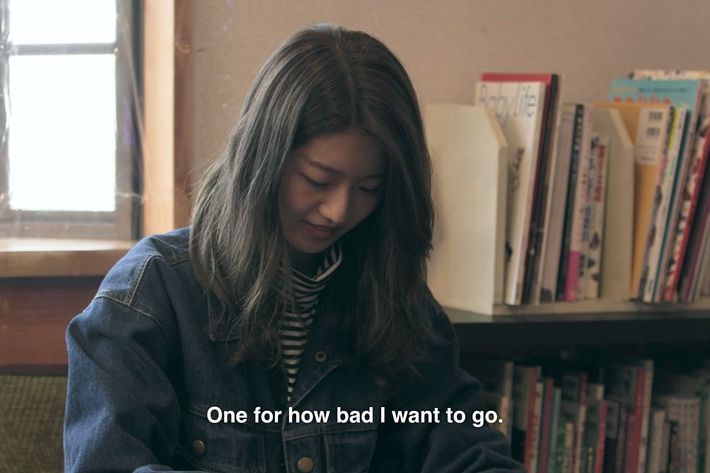

When he becomes interested in Ami Komuro, a sullen and withdrawn student who claims that she wants to date someone who isn’t interested in her, the stars align for disaster. Their courtship is stilted and painful, with Yuudai acting like an awkward child. Rather than asking Ami out, he needles her, repeatedly insulting her like a 10-year-old boy in a playground. Eventually, the two go on a terrible date where neither of them talk and Ami hates every activity, all of which Yuudai has selected. When Yuudai asks Ami to rate how much she wants to continue on different parts of the date on a scale of one to ten, she says one, then three.

Worse still, Yuudai is a chef who doesn’t even cook very well. He enters the house having dropped out of culinary school in order to focus on “actually” cooking, but almost never cooks, like an awkward, unpleasant version of Antoni from Queer Eye. The other members of the house seem to know more about cooking than he does, and when they ask Yuudai to help with their communal meals, he serves up excuses about everything from his real focus on gourmet cuisine to just not feeling like it. When he goes to interview for a job at a restaurant, he wears sunglasses and appears to almost consciously sabotage his prospects. If he won’t work on pursuing his dreams and he can’t have compelling relationships with the other people in the house, what’s he supposed to be doing in the house? Infuriating his housemates, it turns out.

Yuudai isn’t a reality-TV villain in the model of, say, someone on The Real Housewives. He isn’t especially good at manipulating people; he doesn’t have enough understanding of people for that. Instead, what makes Yuudai so compelling is his total lack of understanding of the way he comes off, and his almost pathological inability to comprehend what anyone else is saying to him.

Case in point: Although the other housemates struggle to understand Yuudai, they work to draw him out of his shell and bring him toward emotional maturity. Taka Nakamura, an easygoing 31-year-old snowboarder, sees Yuudai as something of a younger-brother figure, and 26-year-old writer Mizuki Haruta drunkenly cries over her concern for his well-being. This is some of the most excruciating material I’ve ever seen on a reality show: Rather than using his charisma and lack of shame to get attention, Yuudai is an emotional black hole, sucking up everyone in the house while emitting only the same vacant smile. With other reality villains, you can at least ignore them or try to outscheme them. How do you respond to someone who, like those stuffed pandas, demands your attention but is incapable of reciprocating? Even the other people in Yuudai’s life are mystified by his conduct — including his friends, the ex-girlfriend he’s strung along, even his own mother.

Of course, like any great reality villain, Yuudai refuses to admit that he might be at fault for anything that’s gone wrong in his life. When he finally leaves the house in the second half of Opening New Doors, his stated rationale is that the other members of the house stifled his desire to be independent, which is absurd when you consider his overreliance on them for everything. Putting aside his ongoing desire to date a mother figure, what would it even mean for Yuudai to be independent? He ends up with one saving grace: the meal he cooks for the house the night before he leaves. It’s a perfect ending to his time on Terrace House, since it’s just enough of a thread to let you believe that Yuudai might actually make it as an adult one day. After all, the best villains always leave you hoping for redemption.