It’s been a good year for comics — and it’s not even May yet. Just in time for assembling your beach-read shopping list, we present you with a list of the best comics of 2018 so far. A note on methodology: To be eligible, a work had to be a bound volume of comics art released for the first time in English in 2018. That includes collections of individual comics and single-story graphic novels/memoirs. Here they are, in no particular order.

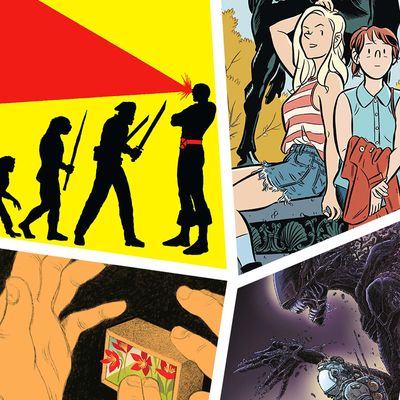

Why Art? by Eleanor Davis (Fantagraphics)

We hardly deserve Eleanor Davis. Mere months after putting out one of the best comics of 2017, the nonfiction travelogue You & a Bike & the Road, she’s hit us with Why Art?, which couldn’t be more of a departure from the previous work, yet somehow still feels like a logical next step in the development of her aesthetic. It begins innocuously enough, with a series of cheekily non sequitur descriptions of art and artists, but it gradually morphs into something much grander. By the end, you’ll be questioning your assumptions about the creative process and artistic consumption, and your awe for Davis will be all the stronger.

From Lone Mountain by John Porcellino (Drawn + Quarterly)

This hefty collection of installments from John Porcellino’s long-running zine King-Cat consists mostly of autobiographical comics, but features hearty helpings of personal miscellany, from little essays on loss and growth to lists of things the author was enjoying at the time of a given zine’s creation. The comics, themselves, are deceptively simple: the lines are few and the anatomy cartoony and basic. But that simplicity makes the work into an emotional Trojan horse, moving past your defenses so it can pierce your heart with its tender insights.

Yellow Negroes and Other Imaginary Creatures by Yvan Alagbé (New York Review)

Yellow Negroes and Other Imaginary Creatures is not an easy book. Its harsh chiaroscuro inks, fractured storytelling, and defiant politics reshape the reader’s brain in real time — a process that’s not necessarily pleasant, but absolutely necessary. Race, color, class, gender, and violence are all ruthlessly dissected in this brief collection of short vignettes (calling some of them “stories” feels wrong) from underappreciated French master Yvan Alagbé, and the end result is one of the most arresting comics works to hit stands in a good long while.

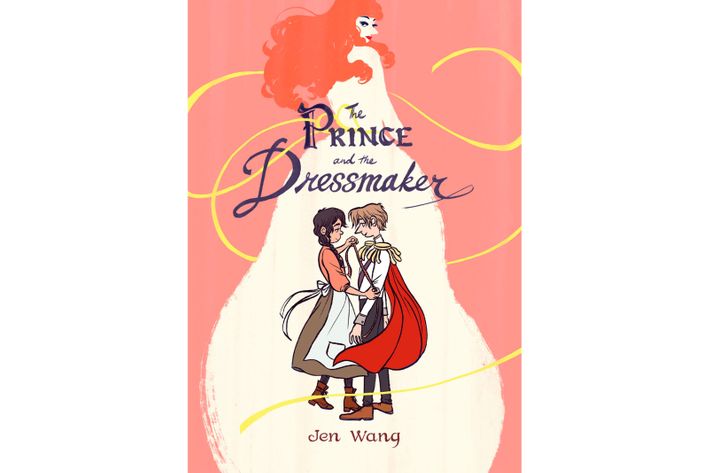

The Prince and the Dressmaker by Jen Wang (First Second)

It’s no secret that we’re in the midst of a youth-comics renaissance, but even in a crowded marketplace, Jen Wang’s The Prince and the Dressmaker stands out. Set in the Paris at the tail end of the horse-and-carriage era, this jubilant story follows two teenagers struggling to find themselves while in each other’s orbit: a poor tailor girl whose talents thrust her into the heights of aristocratic society, and the covertly cross-dressing prince for whom she starts designing. With ecstatic linework, potent colors, and punchy prose, Wang crafts a tale that feels at once classic and — in its effortless undermining of gender roles — utterly fresh. Highly recommended for any youngsters out there with sequential-art addictions.

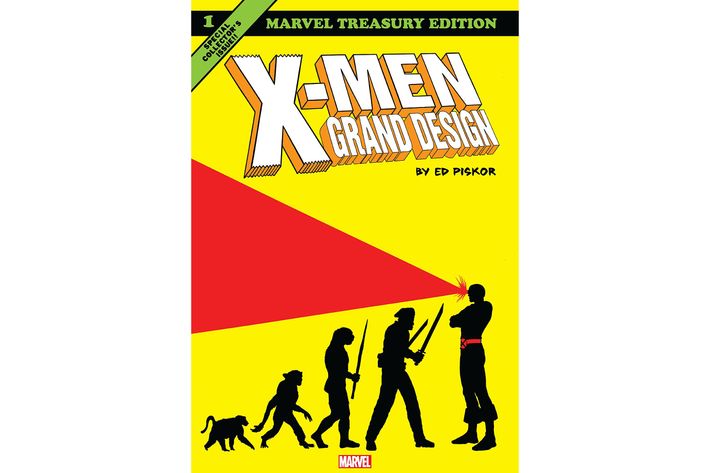

X-Men: Grand Design by Ed Piskor (Marvel)

In fits and starts, Marvel is trying to make the X-Men happen again. For years, the publisher reportedly held back their merry mutants in an effort to spite their movie adaptations, which are helmed by a rival company; but they’re back in the spotlight, most notably in the form of indie cartoonist Ed Piskor’s X-Men: Grand Design. It’s a stunning and simple pitch: let an auteur reimagine the entirety of X-Men history as a unified, heavily tweaked, grittily illustrated narrative. The end result is both a tribute to and advancement of the X-mythos and should prompt superhero publishers to take more risks with their intellectual property.

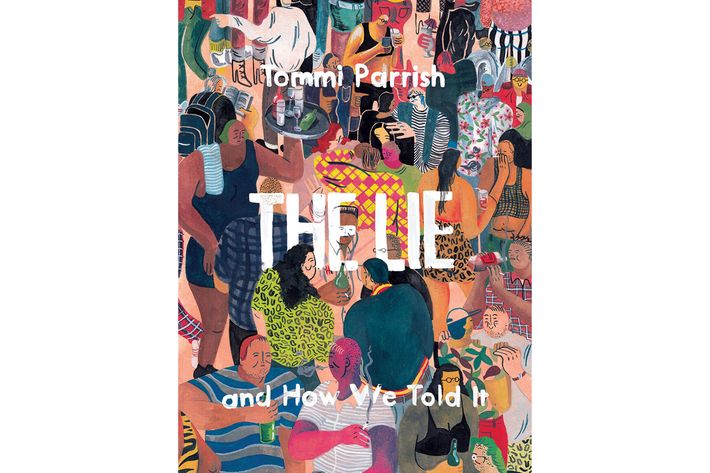

The Lie and How We Told It by Tommi Parrish (Fantagraphics)

It’s a tale as old as time: Two old friends reunite and, as they reminisce, it becomes clear that the ghosts of the old days have never been fully exorcised. Tommi Parrish’s The Lie and How We Told It is a slow-motion gut-punch, using surreal anatomical proportions, rich paints, stories-within-stories, and punctuation-light prose to meditate on sex and regret. Even though very little happens, per se, one finds oneself increasingly on edge, dreading and craving the next twist or turn in an evening of personal revelation. “I had been eavesdropping on a type of life I had never wanted for myself,” reads a sentence near the end, and you’ll find yourself feeling as though you’ve done just that — and wondering whether that type of life is already your own.

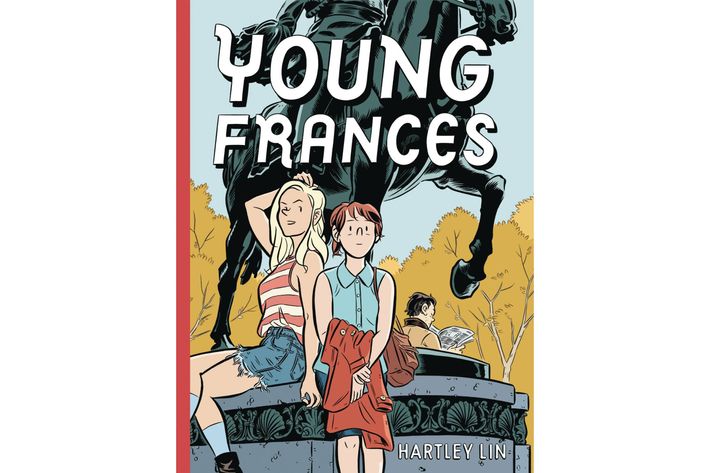

Young Frances by Hartley Lin (AdHouse)

In a world where Dilbert has become sadly synonymous with the alt-right, readers deserve a fresh take on office drudgery, and Hartley Lin has just the thing. In Young Frances — a collection of Lin’s strips from his fantastic Pope Hats series — we spend ample time with the title character, a Canadienne grappling with the question of whether or not she’s throwing her life away by working as a law clerk at a big firm. It eschews simple “screw capitalism” rhetoric in favor of a nuanced take on an assemblage of humans who are all trying to muddle through in their own ways. The artwork alone is worth the price of admission: Lin deploys evocative facial acting and thick inks that sweep with the force of a brisk Toronto winter.

Batman: The Rules of Engagement by Tom King, Clay Mann, Lee Weeks, Michael Lark, Seth Mann, Jordie Bellaire, Elizabeth Breitweiser, June Chung, Clayton Cowles, and Deron Bennett (DC)

While the overall consistency of the DC Comics lineup has evened out and elevated in the two years since its “Rebirth” initiative launched, there are still far too few series that feel like they’re advancing the superhero genre in any meaningful way. Tom King’s Batman is an obvious exception. With his rotating cast of top-flight artistic collaborators, King has put out The Rules of Engagement: yet another winning collection of Dark Knight yarns, all of them circling around the pitch-perfect romance between Batsy and Catwoman. The standout is the “Superfriends” two-parter, in which the happy couple go on a double date with Superman and Lois Lane — it features a bevy of ticklingly brilliant observations about these august characters and the hoary genre they inhabit.

Aliens: Dead Orbit by James Stokoe (Dark Horse)

If only Ridley Scott would read more comics. After the piffle that was Alien: Covenant, fans of the Alien franchise may find themselves despairing in a world where that old xenomorph magic appears to have evaporated from Hollywood. But the saga is alive and well on the page thanks to James Stokoe. Aliens: Dead Orbit is more or less everything one wants from an Alien story, jam-packed with used-future claustrophobia and blood-freezing body horror. Visually, Stokoe is the ideal inheritor of the templates set for the franchise by Moebius and H.R. Giger, crafting a story that transcends verbal language and ascends to the heights of inconceivable terror.

The Pervert by Remy Boydell and Michelle Perez (Image)

The most somber comic featuring a threesome between a cat, a dog, and Jon from Garfield that you’ll read all year. The Pervert is a fragmented journey through the anthropomorphized life of a trans woman making her way in Seattle on call-center gigs and sex work, and it’s full near to bursting with empathy and arresting observation. Remy Boydell’s watercolors deftly illuminate the Pacific Northwest with murmuring sadness and the book’s frank accounts of stilted intimacy ring all too true. The surreal quasi-cameos from famous comics characters are the unsettling icing on this deliciously depressing cake.

All the Answers by Michael Kupperman (Simon and Schuster)

People have a nasty habit of breaking the things they love. In Michael Kupperman’s All the Answers, the remarkably gifted cartoonist explores the personal history of his father, a former child star, and the results are brutal. While he should have been living a healthily anonymous life in grade school, Joel Kupperman was thrust into the national spotlight as the prodigious and beloved star of a quiz show. The book walks us through how, precisely, this experience ruined the boy and the man he became, as well as how the trauma has rotted away at the relationship between Messrs. Kupperman and Kupperman. No one draws in quite the way Michael does, with a style that is at once photorealistic and cartoony, and if you’re used to seeing his talent deployed for humorous effect in books like Tales Designed to Thrizzle, you’re in for a shock and a treat here.

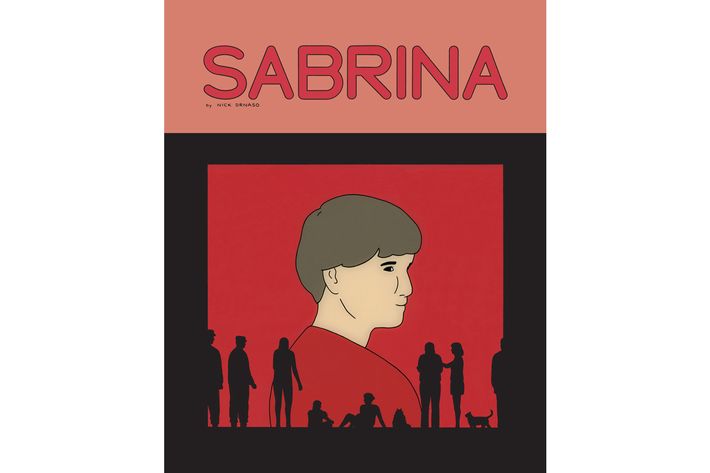

Sabrina by Nick Drnaso (Drawn + Quarterly)

No comic I’ve read this year feels as of-the-moment as Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina. Using his unsettlingly simple figure work, background construction, and coloring, the author pushes himself beyond the heights of his previous work, Beverly, and puts forth a chronicle about the disintegration of the American mind. I’ve probably said too much already, as the book is best consumed with no preexisting expectations or foreknowledge of what’s inside. Just trust that you’ll walk away feeling a curious mix of disgust toward and empathy for the people of this great nation. No small feat.