All week long, Vulture is exploring the many ways true crime has become one of the most dominant genres in popular culture.

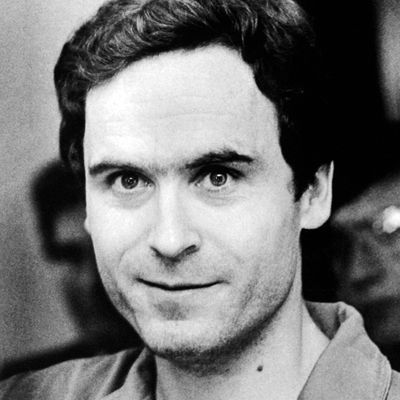

It is a truth universally acknowledged, at least in the true-crime community, that Ted Bundy would be irritatingly pleased with all the attention he’s getting lately. Twenty-nine years have passed since he died in the electric chair, forty since his last murder, forty-four since his first confirmed murder, and seventy-two since his birth, but a brief scan of pop culture seems to indicate that our fascination with the turtlenecked sociopath has reached a new level. Should we be …concerned?

Let’s consider the evidence. Oxygen’s recent series, In Defense Of, features Ted’s lawyer John Henry Browne in the finale; the channel has also launched a two-hour special called Snapped Notorious: Ted Bundy, plus a smattering of juicy online content (“Where Is Serial Killer Ted Bundy’s Daughter?”). Then, 2017 gave us the haunting short film Fry Day, set during Bundy’s 1989 execution, and over the past few years, he’s been exhaustively covered on most of the big true-crime podcasts. Next, 2019 is shaping up to be the year of the Big Bundy Reveal: It’ll bring us Theodore, a documentary by Celene Beth Calderon, the first female documentary director to tackle this subject, and Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, a feature film starring Zac Efron as the killer with the sociopathic smize. The film’s director, Joe Berlinger, is also working on a multi-part unscripted series about Bundy using never-before-seen archival material.

To be fair, Bundy is not the only true-crime “heavy hitter” getting revisited these days. (My Friend Dahmer, anyone?) And serial killers have always been creepily popular: When Bundy was incarcerated in the ’80s, people snapped up trading cards emblazoned with his face and gobbled Bundy-themed dishes at restaurants. But then he was electrocuted, and his white hearse drove off into the sunrise, and his celebrity faded, at least for a while. So why the sudden renewed interest?

“There was a real lull in the attention given to Bundy for 20 years,” says Browne, Bundy’s defense attorney. “I don’t want to be known as Ted Bundy’s lawyer, but unfortunately that’s happening again.” He calls today’s obsession “the Bundy binge,” and is “totally blown away” by it. And he’s not the only one who finds the attention disconcerting. When documentarian Calderon tells her interview subjects that Ted Bundy’s legend is alive and well — that there are Bundy-themed bath soaks available for purchase on the internet — they recoil. They don’t understand why anyone would want to know more about the man who blew up their lives.

Part of this “Bundy binge” is pure practicality: The success of shows like The Jinx, People vs. OJ, Making a Murderer, and Serial incentivizes makers to dredge through old crimes for compelling stories, and since January 24, 2019, will mark the 30th anniversary of Bundy’s death, it’s a natural time to reexamine him. Director Berlinger notes that our “insatiable appetite for crime-related programming” is helped along by technical advances, too: the explosion of TV production in general means that there are more true crime shows to watch than ever before, and the nature of streaming pairs perfectly with the what-happens-next nature of crime stories. In other words, now is the perfect time to glut ourselves on Bundy content, if only for the simple fact that, for the first time in history, we can.

Practicality aside, though, a large part of Bundy’s enduring fascination can be chalked up to his dashing good looks. The Bundy mythos is totally tied up in the idea of handsomeness-as-mask. Elizabeth Munro, an admin for the 223,668-person strong My Favorite Murder Podcast Facebook group, says the cognitive dissonance between his turtlenecks and his atrocious deeds is exactly why we’re still talking about him. “He and Jeffrey Dahmer seem to be the heartthrobs of the serial-killer genre,” she says. “It just draws in people. It’s the weird factor — they can’t seem to put two and two together.” Ted wasn’t actually as dreamy as his legend would have it; reporters who worked with him insisted that he was a “compulsive nail-biter and nose picker,” while on In Defense Of, Browne snipes, “He thinks he’s very likable, but he’s not.” But at this point it hardly matters, because we’re stuck on Bundy like a girl with a crush, forever asking ourselves how evil could wear such a pretty face.

Perhaps it’s precisely that — all that questioning and wondering — that enables us to keep coming back, too. There’s the philosophical stuff: Why? How could he? What was he really like? (“Born evil,” says Browne.) But then there are the chillingly pragmatic questions: Was Ted responsible for more murders than he confessed to? Unsolved crimes in California? In Utah? Oregon? Washington? In 2011, the New York Times reported that his DNA profile finally had been extracted from a dusty vial of blood, and so it’s possible that after decades, certain eerily similar cold cases could be linked to him. If that’s the case, why wouldn’t we keep on trying to know him? Calderon has been interviewing people who’ve never spoken up about Bundy before, and they’re getting older. For those who are still working on these cold cases, there’s a real urgency to figure things out before it’s too late. It’s as though Bundy’s still around, taunting us with his impressive escape record, threatening to slip through our fingers yet again.

That being said, our relationship to Bundy these days is not one of pure terror. As horrifying as his crimes and methods were, the idea of Ted Bundy is not so petrifying that we can’t relax in the tub with a Bundy bath soak, or pop an enamel pin of his infamous beige Volkswagen onto our jean jackets. In fact, his easy commodification indicates that we don’t take him as seriously as we do our more modern criminals. But why? It’s not that threats like Bundy have gone away — it’s that the “Bundy binge” is now aesthetically permissible. Serial killers will always feel like a product of the ’70s and ’80s, when the term “serial killer” was invented, when serial killing peaked, and when DNA had blessedly (for criminals, at least) not yet made its way into the courtroom. Though we very well might be surrounded by serial killers right now (the homicide archivist Thomas Hargrove estimates that there could be 2,000 serial killers in the U.S. as we speak!), they don’t feel like a front-of-mind modern worry. Consider the show Mindhunter, an austerely nostalgic look at the days of serial killing. Or the upcoming film Summer of ‘84, an ’80s daydream with lines like, “There’s a serial killer on the loose. What else could possibly be this exciting?” Or the retro aesthetic of “serial killer glasses.” Or the greeting cards. Or the cross-stitch. Or the memes.

All of this is only made possible because we’re scared of other, less knowable monsters these days. “Our focus has changed, as far as what we’re fearful of,” says Calderon. She adds that every time she goes to the movies, she looks around, wondering if anyone will open fire. Munro says that she’s less afraid of finding a Bundy-esque stranger in her house than she is of seeing an active shooter at the mall, or at work. The 2017 Chapman University Survey of American Fears found that a “random mass shooting” ranked 35th out of 80 fears (with 28.1% of respondents afraid of it), while “murder by a stranger” ranked 60th (with 18.3% of respondents afraid of it). Fears of terrorism and nuclear war ranked much higher still. We don’t have data on the chief American fears from the ‘70s and ’80s, when Bundy headlined every paper, but the survey’s principal investigator, Dr. Christopher D. Bader, reads these stats as “an indication that mass shooters have overtaken serial killers as a key boogeyman in the American mind. Of course, most stranger killings are not serial killings,” he says, “but the murder by a stranger item does give us a window into this fear.”

It doesn’t matter that we were introduced to the phrase “mass shooter” before we even had the term “serial killer” (the former term was popularized in 1966 after the University of Texas tower shooting; the later coined in the mid-’70s by FBI agent Robert Ressler). Just like it doesn’t matter that Ted Bundy picked his nose. What matters, at least in the world of true crime, is how we think of these things, and what we remember of them. We tend to think of the serial killer as an evil that we’ve already figured out (he collects trophies, he is organized or disorganized, his mother was strict!). In contrast, the mass shooter is someone who might still get us. “Uniquely terrifying,” the Washington Post calls mass shootings. (Uniquely terrifying in 2018, that is. In 2048, we might be making movies about them.)

This is how we can treat someone like Ted Bundy as more of an object of detached fascination than a real threat. We can return to our curious questioning: What was he really like? What did his girlfriend think? Did he have a conscience? Did he have a soul? Because his crimes happened in a time that feels hazier, simpler. We don’t wear our hair like that these days. We don’t chat with strangers. We don’t leave our doors unlocked. Instead, we buy transparent backpacks, and take our shoes off at the airport, and watch for different faces in the crowd — furious boys, with guns beneath their trench coats. Bundy was our monster, yes. But he’s not our monster anymore.