All week long, Vulture is exploring the many ways true crime has become one of the most dominant genres in popular culture. While crime-driven storytelling is experiencing a boom in television and podcasts, it’s long been one of literature’s most enduring obsessions. To honor the genre’s roots, Vulture asked a group of crime authors writing today to pick their all-time favorite books about real-life crimes.

Leah Carroll

Author of Down City: A Daughter’s Story of Love, Memory, and Murder.

The Skies Belong to Us, Brendan Koerner

What might have become, in less capable hands, a madcap caper of two bumbling hijackers, is instead rendered as a deeply empathic study of post-’60s American disillusionment. Amid a rash of “skyjackings” in the late ’60s and early ’70s, Roger Holder and Cathy Kerkow successfully seized a commercial airliner and fled across the ocean with a half-million dollars in ransom. Koerner meticulously re-creates their crime and brings a whole lost era — a gonzo inflection point in history — to life. This book is a necessary reminder of the ways crime can echo a society’s values, and why it is necessary to tell those crime stories.

Killer on the Road, Ginger Strand

With scrupulous research and biting wit, Strand tells the grand American story of the creation of our national interstate system — and the killers who quickly claimed the highways as their killing field. This is a finely balanced work of social history and true crime that will make you rethink civil engineering, road trips, and the idea of ever pulling over on the freeway to fix a flat tire. From Ed Kemper, a serial killer who preyed on hitchhiking coeds in the late ’60s (yes, the one from Netflix’s Mindhunter), to the Beltway snipers who terrorized residents of Maryland and Virginia in 2002, Strand tells the fascinating story of the “killers on the road” — and what they mean to the American imagination.

Shot in the Heart, Mikal Gilmore

Norman Mailer’s florid doorstop of a book The Executioner’s Song may be the better-known work about Gary Gilmore, the murderer executed by firing squad in 1977. But the truly definitive account is Shot in the Heart, by Gary’s youngest brother and music journalist Mikal Gilmore. A mix of crime story, memoir, and family history, the book is a search for answers about love, family, and the legacy of violence. Mikal Gilmore is unsparing in his depiction of his troubled family: the frontier Mormonism that shaped them, the poverty and addiction that plagued them for generations, and the federal systems that failed them repeatedly. While Mailer portrayed Gary Gilmore as a folk hero and deadly cipher, Mikal gives us a killer who was both a stranger and a brother — a man many of us could know. This is a crime story, but it’s also a book about ghosts, and like the best ghost stories, the horror that creeps up around the edges can feel unsettlingly familiar.

Vulgar Favors, Maureen Orth

On July 15, 1997, when fashion designer Gianni Versace was gunned down on the steps of his Miami mansion, the world reacted in disbelief. Who would kill such a beloved figure? Vanity Fair journalist Maureen Orth was fairly certain she knew exactly who had done it: a fugitive named Andrew Cunanan that she’d been tracking for months, and who was already wanted by the FBI in connection with the murders of four other men. Orth’s book became the basis for the limited FX series, American Crime Story: Versace. It’s a deftly reported account of Cunanan’s crimes, and Orth’s nuanced depiction of Cunanan as troubled man struggling with his identity never loses sight of what he ultimately was: a killer.

Billy Jensen

Author of Chase Darkness With Me, to be released as an Audible Original in 2019, and contributor to Michelle McNamara’s posthumous I’ll Be Gone in the Dark: One Woman’s Obsessive Search for the Golden State Killer.

Hellhound on His Trail, Hampton Sides

When writing about a tale that has been told a thousand times before, you have to come up with a new device. Hampton Sides tells the story of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. as a collision course, with one chapter following the civil-rights crusader and the next tracing the steps of an aimless loner. As you go back and forth, both the soon-to-martyred King and his assassin are transformed from the archetypes as we know them into the humans they once were. When they finally collide, they step back into their places in history, but you’re left knowing more about both men than you ever knew before.

Bad Blood, John Carreyrou

After The Jinx came out, practically every network was looking to make a true-crime documentary to replicate HBO’s success. The only problem: How can you find another supervillain like Robert Durst? Hold my beer, says John Carreyrou. This is the story of the charismatic Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes, her Svengali-esque second-in-command, and their multibillion-dollar-valued Silicon Valley start-up that claimed it could diagnose hundreds of diseases with a finger prick of blood. Turns out it couldn’t, and the measures the company took to silence critics and whistleblowers will have your jaw dropping. When the company — once valued at $9 billion — begins to crumble, the Schadenfreude washes over you.

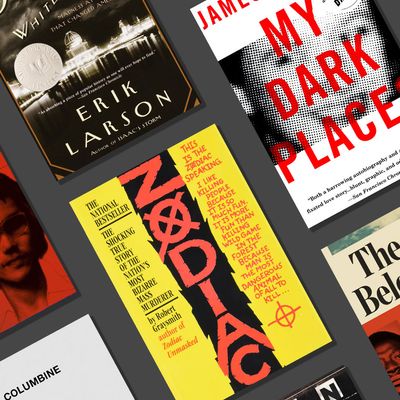

My Dark Places, James Ellroy

Every crime writer has an origin story. When James Ellroy was 8 years old, the body of his mother was found near a ball field in El Monte, California. She had been raped and murdered, and her killer was never caught. Decades later, you ride shotgun with the Demon Dog of crime as he retraces his mother’s last steps. He writes to his mother in the prologue: “Your death defines my life. I want to take your secrets public. I want to burn down the distance between us. I want to give you breath.” He pulls no punches when describing the hard-drinking, hard-partying lifestyle of his mother. And while, ultimately, the book doesn’t identify her killer, you do get to know the pulpy insides of a man who seemingly had no other choice but to become the greatest crime writer of his generation.

Zodiac, Robert Graysmith

This would be on Michelle McNamara’s list. As true-crime writers, we can get obsessed with a case. During her quest to find the Golden State Killer (which became I’ll Be Gone in the Dark), Michelle was careful not to fall completely into the rabbit hole, and Zodiac was the cautionary tale she drew from to bring her back from the edge. Robert Graysmith’s exhaustive obsession with the Zodiac murders drove him to zero in on one suspect — and had him teetering on the edge of madness. It proves that a great story doesn’t need to have an ending wrapped up in a neat little bow.

Laura Lippman

Author of Sunburn, What the Dead Know, and Every Secret Thing, and more.

Evidence of Love, Jim Atkinson and John Bloom

This superb book centers on adulterous lovers who happen to belong to the same church. When the man’s wife confronts her rival, the result is a violent homicide: Candace Montgomery struck Betty Gore with an ax 40-plus times, yet her attorney was able to mount a defense that won her acquittal. (He argued that it was Gore who first brandished the ax and Montgomery was only defending herself.) It would have been easy to be snarky or salacious with this material, but Atkinson and Bloom prove to be compassionate chroniclers of life in Wylie, Texas, part of the so-called Silicon Prairie back when Texas Instruments was a big deal. Candy Montgomery is a small-town Texas version of Madame Bovary, full of inchoate desires, as surprised as anyone by the pain and destruction she causes.

“The Murders at the Lake,” Michael Hall, 2014

I started my newspaper career in Waco, Texas, and was working there in 1982 when three teenagers were killed in a particularly sadistic homicide. It was long believed to be a case of mistaken identity; the working theory was that a convenience-store clerk had paid men to kill a young woman on whom he had an insurance policy, and that the hired killers screwed up. Flash forward to 2014 and I’m back in Texas for my book tour when Texas Monthly publishes “The Murders at the Lake” by Michael Hall. While it’s technically not a book, it’s practically book-length. The 25,000-word piece, the fascinating result of a yearlong investigation, forced me to question everything about a story I thought I knew quite well. Hall’s stellar reporting illustrates how the case continues to haunt everyone connected to it, and raises the possibility that an innocent man was executed — something the district attorney, who declined to be interviewed, vehemently denies. This is the Waco I knew, not the one on HGTV’s Fixer Upper.

Until the Twelfth of Never, Bella Stumbo

A lot of people use the term “Lifetime movie” as a catch-all (and pejorative) for a certain kind of television film, usually those that center on women and crime. But I’ve always loved those movies, and not in an ironic way. One of the best was Betty Broderick: A Woman Scorned, about a first wife who shot and killed her ex and his new wife. Broderick then claimed that she was simply standing up for all the first wives who had been replaced by so-called trophy wives. A young writer who knew of my fascination with the Broderick case thanked me for an endorsement of her work by sending me a copy of Stumbo’s book, the basis for the Lifetime movie. Stumbo, a Los Angeles Times reporter, makes clear that Betty and Dan Broderick were both just thoroughly awful to one another in marriage and divorce, and his refusal to take either spouse’s side makes the book riveting and memorable. Oh, and that young writer who sent it to me was Gillian Flynn, who’d just finished Gone Girl — itself a pretty great take on a toxic marriage. I hope things worked out for her.

Echoes in the Darkness, Joseph Wambaugh

Wambaugh, a former Los Angeles police officer, made his reputation as a crime writer with true stories about cops. But I was always haunted by Echoes in the Darkness, set at a high school on Philadelphia’s Main Line. It has a love triangle (possibly a quadrangle or even a pentagon); a high-school principal with a secret life; and, at the center of everything, the charismatic, almost Rasputin-like English teacher, William Bradfield Jr. I think the technical term for what became known as the Main Line Murder is “crazypants.” Bradfield was accused of masterminding the murder of his colleague and semi-secret lover, Susan Reinert; she was found in the wheel well of her hatchback, beaten and given a lethal dose of morphine. It was believed that the principal, in league with Bradfield, murdered her as well as her two missing children, who were never found. And that’s just where the twisty tale begins. It’s a wild story, but Wambaugh brings intense compassion to Bradfield’s living victims, the sincere and sometimes naïve co-workers who understood only in hindsight how they had been manipulated.

Missoula, Jon Krakauer

Krakauer, working unapologetically as an advocate-journalist, follows five sexual-assault complaints at the University of Montana-Missoula over a two-year period. Some were high-profile criminal cases involving football players; others were adjudicated by the college. The biggest shock in the book, however, is that Missoula turns out to be a pretty average college town when it comes to sexual assault — not the best, but far from the worst. The thing that sticks out for me is how Krakauer refused to be hamstrung by the false equivalency often brought to what many continue to call “he said, she said” cases. Some reviewers criticized the book as one-sided, but that was its power: Krakauer decided to take sides and he chose to believe the women who said they were assaulted.

Carolyn Murnick

Author of The Hot One: A Memoir of Friendship, Sex, and Murder.

The Dead Girl, Melanie Thernstrom

Kirkus called this genre hybrid “self-absorbed” when it was first published in 1990, but viewed through a contemporary lens, the criticism smacks of the sexist language long used to denigrate personal writing by women. And The Dead Girl is extremely personal. A story about the disappearance and ensuing murder trial of the author’s childhood best friend, the book is a lyrical meditation on female friendship and loss, and it was a major touchstone for me when I began writing The Hot One.

Strange Piece of Paradise, Terri Jentz

At 724 pages, Strange Piece of Paradise is not a quick read. But persevere and you’ll be rewarded with a wholly original portrait of the American West, violence, and the legacy of trauma. In 1977, Terri Jentz set off on a cross-country bike trip with her Yale roommate. One night at a campsite in Oregon, a stranger deliberately ran over their tent with his truck and then attacked them with an ax. Both girls survived, and no one was ever arrested. Fifteen years later, Jentz returns to the scene of the crime and finds that not only did townspeople still remember her attack, but they also knew who did it.

After the Eclipse, Sarah Perry

If you’re looking for a perfect example of the unnameable depth that women writers can bring to true crime, read After the Eclipse. Sarah Perry was just 12 when her single mother was murdered at their home in rural Maine — while Sarah was awake and terrified in the next room. As an adult, she goes back to her hometown to examine the police’s case files and talk to everyone she can find who knew her mother. Packed with small-town girlfriends and mourning sisters, After the Eclipse radiates with world-weary women’s voices and lays bare the forces that give rise to poverty and gendered violence.

Down City, Leah Carroll

Leah Carroll’s investigative memoir centers around two heartbreaking questions: Was her mother — killed when Carroll was 4 — a Mafia informant? Was her father’s early death a suicide? Reminiscent of James Ellroy’s masterful My Dark Places, Down City paints a gritty picture of Providence, Rhode Island, in the ’80s and ’90s but glows with a fiercely resilient child’s love for her lost parents.

The Red Parts, Maggie Nelson

You probably know Maggie Nelson from her best-selling queer memoir The Argonauts, but before that book, she published two short volumes centered around her aunt’s murder in 1969, four years before Nelson was born. The first, Jane: A Murder, is a mix of poetry and literary fragments, and the second is this subtle, shape-shifting look at the long-overdue trial of her aunt’s killer and our cultural obsession with pretty dead (white) girls, written in confident and interrogating prose.

Ivy Pochoda

Author of Wonder Valley, Visitation Street, and more.

Lost Girls, Robert Kolker

I know that I am not alone in believing that Lost Girls, in which investigative journalist Robert Kolker tackles the spate of unsolved murders of Craigslist prostitutes in the closed community of Oak Beach, Long Island, is the new industry standard for true crime. The triumph of Kolker’s book is not the crimes themselves, but the author’s humanizing and compassionate examination of the victims — a meticulous and wrenching exploration of the difficult, devastating paths that led four women first into prostitution and ultimately to their deaths. I’m sure there are those who find the serial-killer-shaped hole in Lost Girls inexcusable, but this is exactly what sets the book apart from the field, allowing the victims to transcend their murders and emerge as people rather than casualties.

Columbine, Dave Cullen

I have to admit that I want to resist the idea that this harrowing and psychologically astute investigation of the Columbine massacre is true crime. Yet it is. Entrenched in the broken psyche of America, Columbine is journalism at its very best — comprehensive, surprising, and revelatory. Cullen dispels many of the widely held misconceptions about the massacre (two outsiders taking revenge on the cool kids) and unfolds a tale much more sinister, one that hints at domestic terrorism rather than misguided payback. And in doing so, Cullen’s book shines a light on the way the media can quickly turn rumor into legend at the costly expense of truth.

You All Grow Up and Leave Me, Piper Weiss

When Piper Weiss was 13, her quirky, childlike tennis coach Gary Wilensky committed suicide after he botched the kidnapping of one of his star pupils. Examining this tragedy, Weiss marries true crime to memoir and takes us deep into her angry, messy teenage heart as she leads the reader to understand how easy it is for the manipulative to destroy the vulnerable. In a more traditional book, Weiss would have stuck to conventions of the genre. Instead, she excavates something darker and more personal: Her own disappointment that Wilensky didn’t choose her as his intended victim.

The People Who Eat Darkness, Richard Lloyd Parry

This is, perhaps, the genre at its finest and most strangely satisfying — the disappearance of a young Englishwoman, Lucie Blackman, in Tokyo’s neon hubbub; the trial of Joji Obara, a diabolical and intelligent murderer; and a meticulous exploration of the many subcultures and underworlds of Japan’s capital. Parry, the Asia bureau chief for the Times of London, spent ten years investigating Blackman’s disappearance, covering the lengthy trial (nearly ten years), diving into the confounding intricacies of the Japanese legal system, and ultimately teasing out the Japanese-Korean xenophobia that was the bred-in-bone genesis of Lucie’s murder.

The Killer of Little Shepherds, Douglas Starr

So if Cinemax’s turn-of-the century medical drama The Knick and that old warhorse CSI had a baby, it would be this historical book from Douglas Starr. Told in chapters that alternate between Joseph Vacher, a serial killer stalking the French countryside with a body count possibly reaching into the high 20s, and Alexandre Lacassagne, the father of modern forensics, Starr’s book is a captivating cat-and-mouse game that pits criminal against scientist and scientist against the church. The result is a story that is as compelling as any current ripped-from-the-headlines murder, and one without which, perhaps, the modern canon of true crime could not exist.

Adam Sternbergh

Author of The Blinds, Near Enemy, and Shovel Ready.

In Cold Blood, Truman Capote

Few genres have a clear-cut, indisputable front-runner — but Truman Capote’s stone-cold classic, which recounts the brutal murders of the Clutter family in rural Kansas by a pair of nomadic thugs, brazenly reimagined what true crime could be. An exhilarating mélange of intrepid reporting, sensitive analysis, and exquisitely novelistic storytelling, In Cold Blood was essentially the birth of modern true crime. The ethical issues behind the reporting of the book were thorny enough to inspire at least two films — 2005’s Capote and 2006’s Infamous — and have given journalists plenty to argue about. What no one argues is the power of the book itself: a bleak. beautiful, morbid, poetic, and thrilling testament to the darkness lurking just over the American horizon.

We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families, Philip Gourevitch

Philip Gourevitch’s shattering 1998 account of the Rwandan genocide is not the first book you’d think of as “true crime,” but it definitely belongs here, unless you don’t consider mass genocide a crime. (It also features perhaps the most haunting title in true-crime history, especially once you’ve read the book.) Gourevitch accomplishes an astounding, near-impossible feat: crafting an account that’s both measured and dispassionate while also enraging and heartbreaking, expertly chronicling the complex history of Rwandan conflict in a manner that is impossible to put down. The rare book that is as engrossing as it is important.

The Michigan Murders, Edward Keyes

A grisly tale of a frat-boy serial killer who stalked women — mostly college students — near Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti in the late ’60s, The Michigan Murders is notable less for its sordid details (though there are plenty of those) and more as an artifact of the social friction at the heart of mid-century America. Even as women’s issues rose to the fore on college campuses, a clean-cut psychopath calmly cut down his victims, cloaked in part by his own banality. A chilling reminder of how we can brush up against evil and not even know it, the story even inspired a musical, Michigan Murders.

Witsec: Inside the Federal Witness Protection Program, Pete Earley and Gerald Shur

Co-authored by journalist Pete Earley and WITSEC founder Gerald Shur, this account of the dawning days of the Witness Protection Program is straightforwardly, even mundanely, presented. But that doesn’t matter at all, because the story it tells is so nuts you’d never believe it if it wasn’t true. We now take Witness Protection for granted, having seen it as a plot device in countless mobster movies, but Earley and Shur’s book recounts how a once-unfathomable idea born of prosecutorial desperation — granting amnesty and anonymity to hardened criminals in exchange for testimony — became an effective and even essential element in the fight against organized crime.

Sarah Weinman

Author of The Real Lolita: The Kidnapping of Sally Horner and the Novel That Scandalized the World and more.

The Adversary, Emmanuel Carrère

So much of what I think of as “hybrid true crime” — mixing reportage, memoir, and critical analysis — had its roots, conscious or not, in Carrère’s unorthodox, propulsive examination of family killer Jean-Claude Romand, whose crimes and motivation echo American family killers like John List. Carrère once said he inserted himself into The Adversary as a direct response to Truman Capote leaving himself out of the narrative of In Cold Blood.

Devil in the White City, Erik Larson

The not-so-secret secret of this game-changing best seller, the one that moved true crime into more highbrow narrative territory, is that Larson is a lot more interested in the 1893 World’s Fair narrative than in H.H. Holmes, the serial killer who turned the exhibition into an underground horror show. But with White City, Larson set a new benchmark for writers to meet or exceed in the 15 years since its publication.

Ghettoside, Jill Leovy

Many of my favorite recent true-crime reads have a public-interest or social-justice element (Gilbert King’s two most recent books, Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy, and David Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon, also come to mind). Leovy, a longtime Los Angeles Times reporter, wanted to understand the high per-capita homicide rate in several neighborhood clusters in the city’s South Central area, and why African-Americans are all too likely to be both victim and killer. What she finds does not fit easy narratives, and the detectives she shadows are not heroes but rather just people trying (and often failing) to solve the murders. But if there is to be any real change, we need to understand how we got here, and clear-eyed examinations like Leovy’s are critical to that end.

I’ll Be Gone in the Dark, Michelle McNamara

I chose this as much for what was published — the beautiful, generous, and robust writing that was a hallmark of McNamara’s True Crime Diary blog and the Los Angeles Magazine feature that was the germ of this book — as for what might have been, as McNamara’s sudden death in 2016 robbed readers of what she fully intended. There’s no question, though, that her work was instrumental in solving the Golden State Killer case, and her dogged efforts forced this decades-unknown monster back in the light.

The Poisoner’s Handbook, Deborah Blum

Blum’s expert, fascinating, and concisely written account of the dawn of modern American forensic toxicology also doubles as an origin story of New York City’s Office of Chief Medical Examiner, and how the pathologist and chemist heroes who toiled there solved a spate of mysterious deaths that would have remained undetected without their hard work.

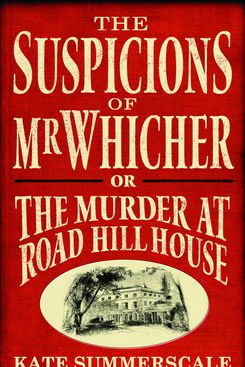

The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher, Kate Summerscale

Summerscale deservedly racked up accolades for her suspenseful narrative account of the 1860 Road Hill House murder case and its devastating effect upon Jack Whicher, one of the founding members of Scotland Yard. Though the case is well-known and much written about, Summerscale’s version is the definitive telling, thanks to its thriller-like approach, full of surprises and shocks for even the experienced true-crime reader.