When V.S. Naipaul was interviewed after the release of Between Father and Son, a collection of the letters he exchanged with his father after moving from Trinidad to Oxford for a scholarship in 1950, he avowed that he hadnÔÇÖt read the book. It was too painful. NaipaulÔÇÖs father, Seepersad, a journalist and unpublished writer of short stories, died at age 47 while his son was away in England. He died again on the first page of his sonÔÇÖs 1961 novel, A House for Mr. Biswas. But there are consolations in this death. He dies leaving his family in possession of a house, even if it is a house still mortgaged and unpaid for; ÔÇ£worseÔÇØ would have been ÔÇ£to have lived without even attempting to lay claim to oneÔÇÖs portion of the earth; to have lived and died as one had been born, unnecessary and unaccommodated.ÔÇØ Moreover, though Mohun Biswas died without riches, he gained an education, unlike his rich brother, and so it was ÔÇ£possible for him to console himself in later life with the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, while he rested on the Slumberking bed in the one room which contained most of his possessions.ÔÇØ

What sets A House for Mr. Biswas apart from NaipaulÔÇÖs later works is the sense of dignity achieved amid an impoverished existence on a marginal colonial island: the image of a poor middle-aged man alone on a mattress reading ancient Stoic philosophy, as set down by his young son living in London, is gently comic and without bitterness, even as it suggests that life might have held more for Mohun Biswas or Seepersad Naipaul if he had been born in the center of things instead of on Trinidad, or if he had, like his son, made the journey to the center. Writing was for the frustrated father and later the celebrated son, as they put it in their letters, a ÔÇ£refusal to be extinguishedÔÇØ and a ÔÇ£wish to seek at some future time for justice.ÔÇØ A House for Mr Biswas, for which Naipaul drew on his fatherÔÇÖs unpublished stories, is, in Pankaj MishraÔÇÖs judgment, ÔÇ£more than just one of the finest twentieth-century novels in English. It is also a valuable historical record of what would have been an intellectually neglected part of the world ÔÇö neglected because sometimes certain worlds donÔÇÖt seem important enough, politically or culturally, to be recorded, and more often they donÔÇÖt produce writers and intellectuals who can note their rise or passing.ÔÇØ It is, in other words, justice attained.

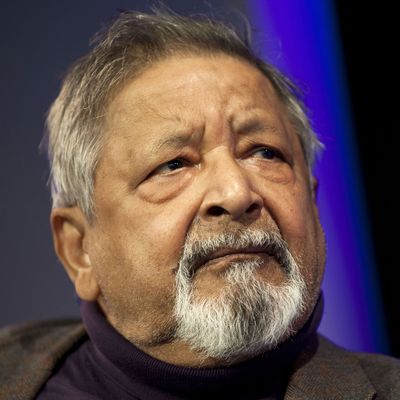

And if that were all Naipaul, the 2001 Nobel laureate who died on Saturday at age 85, were remembered for, the headlines accompanying his death wouldnÔÇÖt so consistently refer to his ÔÇ£complex,ÔÇØ ÔÇ£complicated,ÔÇØ or ÔÇ£impossibleÔÇØ legacy. The sweetness and the sense of salvaged dignity present in his early comic works of fiction shaded more and more over the five decades of his career into bitterness and often unconcealed contempt. Naipaul was a pioneer of postcolonial literature, both in the sense of one who brought news to the capital of unexplored landscapes (from a previously unseen point of view) and as a trailblazer for those who followed him on this path from the margin to the center. But in his novels and books of journalism beginning in the mid-1960s, he entered a political phase that put him on the side of reaction.

I count at least two of these books among my favorites. Call them compromised pleasures. The writing is always gripping, minutely observed, and told in deceptively simple, propulsive prose. His 1967 novel The Mimic Men takes the form of a memoir by Ralph Singh, an ├®migr├® of Indian descent who has returned from London to his island birthplace of Isabella, made a fortune, and then become disastrously involved in politics, only to be exiled to England once more. The bitterness of this book is that of the colonized thrust into the role of the colonizer, a scenario doomed to failure in advance, because the new guard canÔÇÖt help but mimic the old, except without the backing of empire. ÔÇ£One Out of Many,ÔÇØ the most unforgettable of the five narratives in NaipaulÔÇÖs Booker-winning 1971 work In a Free State, charts the humiliations of Santosh, a servant from Bombay who accompanies his diplomat employer to Washington, D.C., in 1968, loses himself in the city and lives in terror of deportation, knowing that he canÔÇÖt return to his old life. The accompanying narratives tell of a West Indian migrant in London seized by homicidal mania and a pair of English characters on a panicked drive through a country resembling Uganda on the eve of a dictatorÔÇÖs (read Idi Amin) consolidation of power.

Pessimism isnÔÇÖt strong enough a word for these booksÔÇÖ portrayal of the postcolonial situation. Naipaul elaborated on this dire vision in Guerillas (1975) and A Bend in the River (1979), which expanded on and fictionalized his earlier journalistic accounts of the Black Power killings in Trinidad and Zaire under Mobutu, respectively. Writing in 2002, Edward Said took this view of NaipaulÔÇÖs middle phase:

ÔÇ£In the 1960s V.S. Naipaul began, disquietingly, to systematise the revisionist view of empire. A disciple and wilful misreader of Conrad, he gave Third Worldism, as it came to be known in France and elsewhere, a bad name. He didnÔÇÖt deny that terrible things had happened in such places as the Congo, but, he said, there was idealism of effort, too (remember Father Huisman in A Bend in the River); and monstrous post-colonial abuse had followed. He didnÔÇÖt actually say that King Leopold, bad though he was, was probably not much worse than Mobutu, or Idi Amin, or Mugabe, but he allowed one to think it.ÔÇØ

Said also emphasized NaipaulÔÇÖs ÔÇ£hostilityÔÇØ to Islam and Arabs and an essentially apologist attitude toward the British Empire: ÔÇ£when Naipaul was recently quoted as being content that the Indians no longer blame the British for everything it seemed to me a typically superficial quip that hides the truly immense intellectual labour that is still required to understand how much the British really were responsible for.ÔÇØ Indeed, Naipaul in interviews was often harsher in these attitudes than he was on the page because in person he could be glib. In 1979, when Elizabeth Hardwick asked him about the marks married women in India wear on their heads, he said, ÔÇ£The dot means: My head is empty.ÔÇØ Of Africa, he told her, ÔÇ£Africa has no future.ÔÇØ These comments arrive in the midst of HardwickÔÇÖs sensitive reading of the novels and their ÔÇ£balance of negative forcesÔÇØ: ÔÇ£The sweep of NaipaulÔÇÖs imagination, the brilliant fictional frame that expresses it, are in my view without equal today.ÔÇØ

Writing a few years later, Joan Didion echoed this evaluation, maintaining that Naipaul reserved his true contempt not for those who bought into the rhetoric of ÔÇ£the familiar image of the new world emerging from the rot of the old, the free state from the chrysalis of colonial decayÔÇØ but those who sold it: the secure middle class of the developed world. This contempt for dabbling hippies like John Lennon wasnÔÇÖt incompatible with the high-society connections Naipaul forged among London conservatives.

But those connections never turned him into a knee-jerk right-wing crank, particularly when it came to the United States. His report on the 1984 Republican Convention in Dallas is as contemptuous as anything he ever wrote. Here he is on Reagan accepting the nomination: at the climax of the great occasion, as at the center of so many of the speeches, there was nothing. It was as if, in summation, the sentimentality, about religion and Americanism, had betrayed only an intellectual vacancy; as if the computer language of the convention had revealed the imaginative poverty of these political lives. A chapter on Rednecks from his 1989 travelogue A Turn of the South is only mildly more sympathetic, laced with an ironic condescension: at a farm in Mississippi they were, bareback, but with the wonderful baseball hats, in a boat among the reeds, on a weekday afternoonpeople whom  I might have seen flatly, but now saw as people with a certain past, living out a certain code, a threatened species. This arrives after a lengthy monologue from a local trader in real estate about his social inferiors alcoholism, idleness, obesity, and mindless love of country music.

A relatively serene autobiographical novel, The Enigma of Arrival, about Naipauls settling on a manor in Wiltshire in the South of England, arrived before he entered his late phase. As Amit Chaudhuri has argued, writing over the weekend in the Guardian, that book anticipated W.G. Sebalds hybrid work and the autofiction wave thats followed. Chaudhuri is also right that a general rejection of Naipauls politics and attitudes threatens to obscure his achievements as a literary artist. Yet this has only become a more difficult predicament in the decades since Didion identified Naipaul as the ultimate case of brilliant, but  There was his hymn to his own ambition and the pursuit of happiness delivered in 1991 at the Manhattan Institute, under the title Our Universal Culture. What seemed to be universal about it was the cult of success, especially his own. There were a few score-settling essays aimed at peers like Derek Walcott and former friends like Anthony Powell, uncharacteristic among other stories of his literary generosity in person, notably Teju Coles.

But in the end he turned his contempt on the form of the novel itself, in a pair of books he claimed he wrote only to fulfill a publisherÔÇÖs contract. I recall 14 years ago putting down NaipaulÔÇÖs last work of fiction, Magic Seeds, with a distinct sense of repulsion. In one of the last scenes, the narrator, an Indian-born writer and authorial alter ego, attends the wedding of the son of a West African diplomat whose ambition was ÔÇ£to have sex only with white women and then one day to have a white grandchild.ÔÇØ The son is now marrying the mother, an Englishwoman, of his two sons ÔÇö one who is dark, the other ÔÇ£as white as white can be.ÔÇØ During the ceremony, one of the children farts audibly, and the guests ÔÇ£lined up correctly on this matter: the dark people thought the dark child had farted; the fair people thought it was the fair child.ÔÇØ If this is meant as a joke, itÔÇÖs impossible to laugh. As Theo Tait put it in a review for the LRB: ÔÇ£the term ÔÇÿpolitically incorrectÔÇÖ doesnÔÇÖt begin to cover it ÔÇô ÔÇÿpolitically obsceneÔÇÖ is nearer the mark.ÔÇØ Moreover, itÔÇÖs a coarse betrayal of NaipaulÔÇÖs natural comic gifts.

Four years later, Patrick FrenchÔÇÖs authorized biography The World Is What It Is drew on candid interviews with Naipaul as well as his first wife Patricia HaleÔÇÖs diaries, and caused scandal with its revelations of his abusive relationships with Hale and his sadomasochistic affair of decades with his mistress Margaret Gooding. Norman Rush put it this way: ÔÇ£the sympathy elicited by his heroic overcoming of the obstacles facing a poor ÔÇÿTrinidadian of Hindu descentÔÇÖ in racist London and its literary world of the 1950s and 1960s are dissipated by the horrific account of his conduct with the women in his life. This material is so dire that some readers will be tempted to pick up the lens of abnormal psychology in order to interpret much of his work.ÔÇØ As James Wood put it, without diminished sympathy, the wounded man became the inflicter of wounds. Because Naipaul arrived when he did, and with such a grand talent, the wounds were of a global scale.