Adventure Time was never at a loss for memorable characters. The Cartoon Network show — which airs its final episode Monday night — got a lot of mileage out of its central duo of Finn and Jake, of course, but one of its central strengths was the way that it didn’t really need them to keep things moving. Episodes focused on everyone from the too-cool Marceline the Vampire Queen and the scientifically gifted, ethically confused Princess Bubblegum, to largely one-off goof characters, like aspiring mystery writer Root Beer Guy and unlucky criminal Princess Cookies. But Adventure Time’s best character was the one who seemingly had the least depth, at least at first: Ice King.

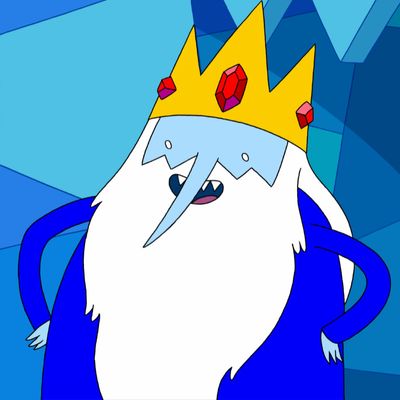

When the show began in 2010, Ice King was a comically exaggerated kids’ TV antagonist. An old, blue-skinned man with a magic crown and a mean streak, he spent most of his time flying around the Land of Ooo trying to kidnap one of the other main characters, Candy Kingdom ruler Princess Bubblegum — or failing that, any of the many, many other princesses in the show’s world. As a recurring villain, Ice King could be menacing when he tried, but there was never any doubt that Finn and Jake would take him down. Even Ice King’s organs were evil: After a failed experiment, his heart gained sentience, left his body, and became a villain of its own known as Ricardio the Heart Guy, voiced by George Takei. In those early episodes, Finn and Jake were trying their hardest to be adventurers, righting wrongs and saving princesses. They were living in a cartoonish version of a Dungeons & Dragons campaign, so there had to be an evil wizard. But as Adventure Time went on, it became clear that Ice King wasn’t just, or even mostly, malicious. He was sad.

In season two’s “The Eyes,” Finn and Jake spend a sleepless night haunted by a creepy-looking horse staring into their souls — only to discover that the observer is actually Ice King in an inflatable horse costume. The reason? Because Ice King is miserable and Finn and Jake always seem to be so effortlessly happy. Ice King’s creepy spying was a sort of rudimentary attempt at self-help, at learning the secret of happiness. In this episode and many others, Ice King’s bumbling largely stems from the way he feels slightly out of sync with the rest of the world. He gets angry that no one invited him to a party, but it turns out he just didn’t open the invitation. He accidentally rebrands as the Nice King after shaving and putting on a sweater, until his beard (and his rage) eventually get the better of him. He builds a Frankenstein-esque princess out of body parts from other princesses, and then tries to act as a supportive, loving husband, but when Princess Monster Wife decides to return her stolen body parts, he complains about her selfishness.

Each time, Ice King comes thisclose to real compassion, like a prestige TV antihero designed to keep the viewer dangling on the edge of their seat. But unlike those characters, Ice King tries to put his heart — George Takei and all — in the right place. (Especially as it becomes clearer that he really thinks of himself as being best bros with Finn and Jake.) More importantly, he really doesn’t understand why what he’s doing is wrong. As Adventure Time progressed, the show delved into Ice King’s tragic backstory as the suave archaeologist Simon Petrikov, a human cursed by the magic crown to an eternity of insane rambling. Ice King’s desire for “princesses” stems from half-remembered echoes of Simon’s old girlfriend, Betty. Even his insanity was a conscious decision, a sacrifice he made after putting on the crown to save a young Marceline.

These layers awkwardly stack on top of each other, making it easy for viewers to latch on to different parts of Ice King. The writer Lev Grossman compared watching Adventure Time to the experience of watching his father suffer from Alzheimer’s disease, but he also described watching the show with his young daughter, who perhaps responded more strongly to Ice King’s schlemiel nature and his unfortunate tendency to get his “hams” (that is, legs) smacked around. More than anything, what makes Ice King such a great character is the way his different modes and different personalities became a stand-in for a wide variety of problems, ranging from the intense (Alzheimer’s disease and depression) to the unfortunately relatable (being so awkward no one wants to hang out with you). He’s got a giant psychic itch, and he’s constantly scratching it in ways that make the problem worse. For people who frequently deal with anxiety and stress through goofy humor, Ice King is a years-long “I felt that” meme. But even though he’s such a relatable character, there’s no risk of him ever becoming the protagonist or sucking up all of the oxygen the way a similarly complex, tragic character might on another series. He’s George Costanza, not Jerry Seinfeld.

By the end of the series, Ice King has become a sort of grotesque sitcom neighbor, always showing up when he isn’t wanted while coming through exactly when he’s needed. He goes on magical road trips with his wizard friends. He lives with Finn and Jake for a while. He’s even made decent progress navigating what Simon calls the “labyrinth” in his brain. Throughout, voice acting legend Tom Kenny imbues Ice King with equal parts pathos and insane, pathetic comedy. But there’s a dangerous lesson in Ice King’s appeal as a character. His magic crown is a powerful metaphor precisely because it allows him to give up personal responsibility. The prospect of pawning off your actions and decisions is as powerful and tempting as ice magic itself, even when you haven’t had to make a tragic bargain. In one episode, Finn watches Ice King accidentally ruin a party and ponders, “It’s like some part of him wants to be a sad wong lord,” a feeling that will resonate with anyone who’s had that friend whose life is constantly in crisis for reasons everyone else can plainly see.

The same thing that make Ice King’s problems so “relatable” — the way his backstory gives him license to wallow in his own pain — feels like its own sort of cautionary tale. What makes Ice King so heartbreaking is that he doesn’t want to engage in most of those behaviors, and only does so because he can’t quite understand the effects of his own actions. Deep down, there’s a part of himself that doesn’t want to be sad. In Ice King’s perfect world, he would be in a stable and happy relationship with a princess and spend most of his time hanging out with his best buds Finn and Jake. The problem is just that he doesn’t know how to get there — at least not without help, which is perhaps Adventure Time’s most important message of all. If we forget it, we run the risk of taking on one of Ice King’s worst, most unfortunate attributes: remaining frozen.