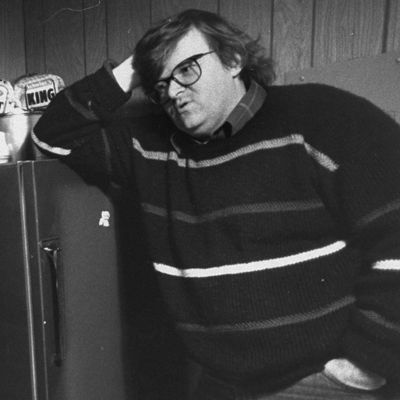

“One of the mosquito-bite irritations of being on the left is finding your ideals represented in public by Michael Moore.” That quote from Vogue film critic John Powers, written about Moore’s Oscar-winning Bowling for Columbine, encapsulates all that’s great and troublesome about the celebrated, divisive filmmaker. More often than not, Moore makes movies that speak to our personal political leanings — and yet, more often that not, we find ourselves arguing with them anyway, lamenting the easy jokes and cheap grandstanding that often substitute for incisive commentary. And even in his finest films, Moore’s presence proves to be a double-edged sword: Too often, he allows his own ego to influence creative decisions, putting himself above the stories he’s telling. Like Bill Maher, his toxic smugness can be repellent, even if you agree with every word.

But what remains Moore’s saving grace is his big, messy sentimentality — his unabashedly sincere belief in America as a nation striving for greatness. That belief can be quite moving, and it elevates his weaker efforts while electrifying his most epochal films. You can argue with his technique or his lack of subtlety, but you can’t dispute how much he cares. Michael Moore may be a fool, but he’s our fool.

With that in mind, ranking his ten films (including one fiction feature) can be a bit agonizing. There are so many good intentions here — but also so many bum notes and misfires. But let’s be honest: We’d miss his rambunctiously undisciplined, impassioned works if he stopped making them. He may be an irritation, but we need his bulldozer spirit — if only because he’s even more of an irritant to the people his righteous movies target.

10. The Big One (1997)

Moore’s third film, and second documentary, isn’t much of an investigative piece at all: It’s instead like a band tour film, except the band is Michael Moore and the tour is Moore being driven around the country promoting his book Downsize This. The movie is as slapdash as it sounds, with only a few highlights, mostly of Moore talking to downtrodden people he sees on his travels — but there are many, many scenes of Moore complaining about all the people whose job it is to help him on his book tour. In a nice bit of Roger & Me symmetry, he does end up getting an interview with a big CEO, Nike’s Phil Knight, but Knight sort of dominates the interview and inadvertently makes you wonder what would have happened if Moore had caught up with Roger Smith.

9. Where to Invade Next (2015)

Moore is a filmmaker and pundit who, from the very beginning, has needed a worthy adversary, whether it’s Roger Smith, Donald Trump or, his most infamous quarry, George W. Bush. When he doesn’t have one — or if he’s just trying to hold the feet of Barack Obama, someone he otherwise admires, to the fire — he’s a bit adrift. The conceit of this documentary is that every time the United States wants something from a country, they invade it, which leads to a series of stilted scenes where Moore goes to another country and praises it for what the United States doesn’t have. It’s hardly a high concept — it takes a long time to explain, and even the title is awkward — and Moore is sort of just idling in his shtick here. Don’t worry: The real villain was coming.

8. Canadian Bacon (1995)

Moore’s one fiction film has a rather obvious conceit: A U.S. president (Alan Alda, funny as always) who’s looking for an enemy to go to war with to boost his poll numbers decides to invade … Canada. Madness ensues! The first half of this is light years better than the second half; Moore knows how to set up his story more than he knows how to finish it off. There’s a funny scene in which several characters sing along to Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” without understanding what it means, and it’s nice to see John Candy (in his last film), but this thing completely falls apart and barely staggers to the end of its 90-minute running time. It should not be considered a surprise that Moore never made another fictional film. Somewhat amazingly, the cinematographer on this film was the great Haskell Wexler, the Oscar-winner responsible for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Bound for Glory.

7. Michael Moore in Trumpland (2016)

As a general rule, with a few exceptions, the less a Michael Moore movie has of Michael Moore, the better. So we’re already behind the eight-ball here with Moore’s one-man show, filmed on the eve of the election, imploring Americans to vote for Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump. As usual, you admire the cause over the execution, and with his long hair and increasingly desk-pounding demeanor, he feels less like a man of the people than he ever has. Still, he has evolved into a relatively skilled performer, and he gives appropriate warnings about the coming Trump storm with working-class families in the Rust Belt. If only Moore could have gotten more of them to listen.

6. Capitalism: A Love Story (2009)

Released in the wake of the financial crisis, Capitalism: A Love Story is an unfocused but appropriately angry jeremiad against the corporate structure that led to the collapse. Moore sprays venom in all directions, from usual enemies like George W. Bush and his Republican allies to the whole political system and how it is run by banks and Big Money. He’s right, and the movie is compelling in Moore’s usual way, but it’s a little too close to the topic at hand to do much more than shake righteous fists. (The Big Short would make the furious case so much better six years later.) He does get points for showcasing both Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders before either was a mainstream figure. We’d be seeing plenty of both of them soon enough.

5. Fahrenheit 11/9 (2018)

There’s a heartbreaking documentary about the Flint water crisis folded into the middle of this scattershot critique of Donald Trump’s 2016 election. Fahrenheit 11/9 is best when it finds Moore digging into the government negligence that paved the way for the poisoning of a Michigan community, and you can sense the Oscar-winning filmmaker’s anger over what’s happened to his neighbors. In other words, it’s the Moore we knew from Roger & Me — relatable, restrained, powered by his righteous fury. As for the rest of 11/9, it’s too much like his other recent works, balancing good points with dopey grandstanding, telling you what you already know and then occasionally hitting you right between the eyes with the passion of his assault. 11/9 reaches a sobering conclusion — maybe the better America we dream of will never come true, and is in fact already a lost cause — but the movie doesn’t quite feel like the bracing, definitive portrait of life in Trumpland that advocates would have preferred.

4. Sicko (2007)

Moore’s secret talent, when he gets out of the way, is getting Ordinary Americans to sit down and tell their stories, plainly and often devastatingly. So a whole film of frustrated, defeated Americans sharing their health-care horror stories works extremely well, almost start to finish; the stories are enraging. Moore has a few of his usual gimmicks, including a confusing scene in which he uses a megaphone outside Guantanamo Bay to demand that Americans get the care the prisoners are getting (does he want them to get less? Or more?). And a scene where he pays the medical bills of the webmaster of a site that hates him feels particularly self-aggrandizing. But when this thing focuses on the pain the American health-care system has caused, it is searing. Particularly when many of the same problems exist more than a decade later.

3. Bowling for Columbine (2002)

Moore won his Oscar for this study of America’s fascination with guns, a topic that has lost none of its potency in the subsequent two decades. Bowling for Columbine doesn’t provide many answers, but it does good work in explaining the culture of fear and violence that allows such an obsession to fester. Moore’s lack of focus has often been his weak spot as a filmmaker, but here everything he touches feels connected — there’s something primal about our gun lust, woven into the fabric of the nation, and the documentarian pulls at those threads, wondering why we’ve lost our minds. There are still jokes, but Columbine might be the moment where Moore consciously pivoted away from satire. After this film, anger and frustration would come to overwhelm his sense of humor about the nation’s ills.

2. Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004)

The highest-grossing nonfiction film ever. One of the few documentaries to win the prestigious Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. Fourteen years later, it’s hard to explain precisely what a big deal Fahrenheit 9/11 was at the time — a major artistic swing for the fences from a significant filmmaker taking on the most meaningful issue of the day. The current political documentary landscape is unthinkable without 9/11, which was an unapologetic polemic meant to sweep George W. Bush out of office during the 2004 presidential election. Spoiler alert: Moore failed in his task, but for all its shortcomings and cheap shots, 9/11 remains a time capsule of what it felt like to be living in America in the wake of the contested 2000 presidential campaign and the Iraq War. Moore doesn’t synthesize the era so much as he stirs up those feelings, calling on his viewers to get angry and mobilize. 9/11 was a balm, if not an effective political tool.

1. Roger & Me (1989)

It is important to remember the context of Roger & Me. Right as the Reagan ’80s, and all the Greed Is Good that came with that, were ending, here was a schlumpy alt-weekly editor with a beaten-up old baseball cap showing us, in unassuming and fiendishly funny terms, the result of all that excess. Closed auto plants, abandoned workers, and once-great cities in decline: If anything, Roger & Me saw the future. Moore is, for perhaps the only time in his career, an immensely likable Everyman, a guy just trying to get a basic answer to a basic question: Why did General Motors do this to my town? The movie did feel a little Mark Twain-ish — wit and rough charm for a greater, satirical purpose, and a funny, sad look at a town whose residents are now selling rabbits as pets or meat. Is it manipulative? Of course. But it plays it much straighter than later Moore films, and with good reason: It has a clear bad guy, who stands in for all the other ills … but is monstrous enough on his own. Moore may have only been the little guy once, but what a little guy he was.

Grierson & Leitch write about the movies regularly and host a podcast on film. Follow them on Twitter or visit their site.