Vulture’s new regular feature, Lit Parade, has been homing in on books that are getting an array of critical attention and sorting out what the reviewers have had to say. The literary terrain has been shifting under our feet for some time. The last two decades have seen a dwindling of regional newspapers and their books pages. The influence of the New York Times has perhaps never been greater. At the same time, numerous online publications have joined venerable outfits like The New York Review of Books and Bookforum with a commitment to longform literary criticism. Profiles and author interviews abound, as does that distinctly contemporary phenomenon, the self-promotional essay penned by the author of a new book. There’s a lot going on both at the center and on the periphery. It can be hard to separate scrutiny from publicity, insight from hype. Lit Parade aims to bring it all together and make some sense of it.

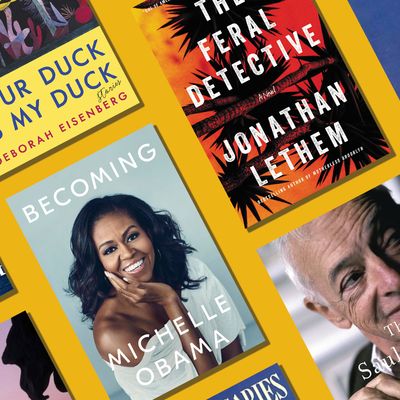

What should we expect to be hearing about in the next few months? September has already seen vigorous conversations about Lisa Brennan-Jobs’s memoir Small Fry, Merve Emre’s biographical history of the Myers-Briggs test, The Personality Brokers, and the final volume of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s autofiction extravaganza My Struggle. Discussion of Francis Fukuyama’s Identity has been accompanied by much fretting about the fate of liberal democracy, the form of government he once argued was bringing about the end of history. Still to come are Brian Dillon’s Essayism, a meditation on the essay form, and Deborah Eisenberg’s short story collection Your Duck Is My Duck. In recent years, we’ve often heard that we’re living in a golden age of the essay, so Dillon’s book provides an opportunity to measure our recent stars against the likes of Montaigne and Virginia Woolf. The short story, meanwhile, can sometimes seem like a form left over from another time, but Eisenberg is one of our acknowledged masters of the form. A new collection of hers is an invitation to look at the life of the form itself.

In October, Haruki Murakami returns with his first novel in four years, Killing Commendatore. At a glance, all the elements of a big Murakami production are present: a middle-aged man who finds himself alone and ends up on an existential quest; a reckoning with the legacy of World War II; a journey into a literal and metaphorical underworld; and an intertextual engagement with a classic work from the West — this time, Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Murakami readers tend to fall into three camps: the enchanted, the unenchanted, and the formerly enchanted but currently disenchanted. The Times has tended to be friendly to Murakami over the years, and critics more skeptical of his work, like Tim Parks, have had their say in the pages of the New York Review. With the Nobel Prize in Literature suspended for a year — Murakami is a perennial favorite with the bookies —the new novel will be a test of how strong his spell remains, of whether he can re-enchant his former admirers.

Just short of 700 pages, Killing Commendatore isn’t the longest epic on offer in October. Uwe Johnson’s Anniversaries, translated from the German by Damion Searls, arrives in two volumes, totaling nearly 1,700 pages. First published in Germany in the early 1970s, Anniversaries is a novel of New York City in the form of diary entries by a German woman living in Manhattan, obsessively following the Vietnam War and American politics through the lens of the New York Times between August 1967 and August 1968. The novel is also informed by the experience of the Second World War in Germany. It will be interesting to watch whether it’s welcomed as a classic novel of New York as it long has been considered one in Germany.

Jonathan Lethem’s The Feral Detective, his 11th novel, marks his return to detective fiction for the first time since 1999’s Motherless Brooklyn. Again Lethem has turned out a postmodern sort-of detective novel, forsaking his native Brooklyn for the desert of California. Set in 2017, it’s one of the first forays by a major American novelist into the timezone of the Trump administration: the narrator worked for the New York Times Op-Ed page before resigning over its election coverage and fleeing New York. Trump has fueled her latent existential rage, much in the way toxic waste sites increase cancer rates. Lethem has a loyal readership, but it’s been a few books since his last critical smash, The Fortress of Solitude. Whatever it says about its author, this book figures to be a bellwether of the way the fiction of the Trump era will be written and received.

Zachary Leader’s two-volume The Life of Saul Bellow comes to a close in November, in a book spanning from 1965, after the publication of his (second) masterpiece Herzog, to his death in 2005. Bellow was the subject of a controversial biography during his lifetime; many thought James Atlas’s 2000 effort gave the Nobelist short shrift, including the subject. Leader is a master of the second-time-around life of the writer: he also performed the task for Kingsley Amis. He’s a great collector of receipts (in Amis’s case, bar bills). Bellow’s legacy has been in flux since his death, and the completion of this life study will surely bring his loyalists (like James Wood and Martin Amis) out for one last tribute. Critics like Vivian Gornick and a younger generation of readers have been ready to dismiss him as another “midcentury misogynist,” in the words of Emily Gould.

A legacy of a different kind will be on display in Michelle Obama’s memoir Becoming, timed to arrive just after the midterm elections, perhaps not to distract Democratic voters from the urgent task at hand. At this point in history it’s hard to expect more from the former First Lady than a high-quality celebrity memoir, but critics can be forgiven if they feel inclined to enhance a politically airbrushed book with their own thoughts on the Obama era and how far the country’s governance has sunk since. A more intriguing question is whether Michelle Obama will use the book to launch her own career in electoral politics.

One author unlikely to use the November publication of his new book to campaign for office is Jonathan Franzen. The novelist’s essays and interviews tend to be greeted on social media — that modern phenomenon he loathes — with gleeful disrespect. Critics haven’t exactly warmed to him as an essayist as they have to his novels. His fiction tends to deliver a broad narrative sweep, while the books of essays gather the piecemeal gripes of a morally committed but committedly cranky guy who you sense might rather be writing fiction. One thing is certain: He deserves better than the hypercranky misreadings he usually gets on the Procrustean bed of Twitter.