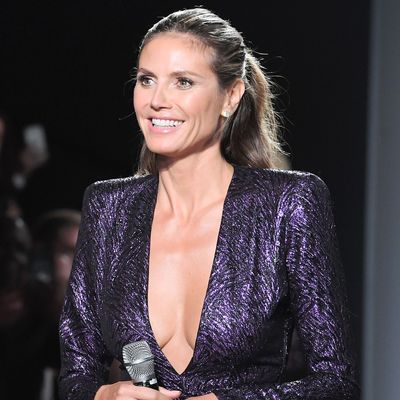

The heart has been ripped from the chest of Project Runway: Tim Gunn is departing, and so has the fashion competition’s soul. I’m done! No more Project Runway for me! cried the internet when the news broke that Tim and Heidi Klum would not return.

What’s left of the show has slumped to the ground, but Bravo is convinced that everything is just fine: “The series will continue its iconic impact with Bravo’s reboot for the next generation of designers and fans,” the network said in a statement. “We are excited to announce our new host and mentor very soon.”

What is there to be excited about? Project Runway without Tim Gunn is Project Runway All Stars, and no one wants that. Swapping out the other judges and keeping Tim Gunn as the nucleus around which everything swirls, like on Project Runway Junior, works. But this is too much of a loss.

Or is it? Maybe Project Runway is a strong enough format to survive a drastic transplant. After all, The Great British Bake-Off survived being desiccated when it lost its beloved judge, Mary Berry, and pun-factory hosts Sue Perkins and Mel Giedroyc.

When they announced their exit two years ago, I wrote that The Great British Baking Show’s production company and new network were “delusional” to insist “the show [viewers] love will remain wholly familiar.” The house had burned down, I declared, and even if the frame is still up, it’s still destroyed. Time to dump it in the bin.

But the house was still standing, and not damaged at all. Season eight, which just premiered for U.S. viewers on Netflix, is still fundamentally the same show, and it’s just as entertaining, perhaps an A- instead of an A+.

Bake-Off offers a fascinating example of how resilient formats can be. In the U.S., we’ve now had four different versions of The Great British Bake-Off: a CBS adaptation that aired in 2013; the original BBC version, which PBS started airing in 2015; an ABC adaptation that started as The Great Holiday Baking Show and became The Great American Baking Show; and now the Channel 4 version on Netflix.

Of those, only the CBS incarnation didn’t work, with Jeff Foxworthy’s hosting and CBS’s insecurity turning a competition for a trophy plate into a more dramatic (cymbal-crash!) game for $250,000.

ABC’s Baking Show retained the U.K. magic because it kept Mary Berry and even the U.K. location. But then she left, and Paul Hollywood took her place for season three, and it still felt warm and familiar. All the while, the GBBO format was there, like a sturdy tent in the English countryside, keeping things contained.

Does a show just need to keep one or more consistent cast members in order to not fall apart? Housewives come and go on the Real Housewives franchise, but it’s never a complete changeover, so there’s discomfort wrapped in the familiar blanket of rich people sniping at each other. Once a format becomes familiar or beloved to viewers, it’s much less unsettling for there to be cast changes.

Yet doing that didn’t work for CBS’s Baking Competition, which had Paul Hollywood as one of its judges, because CBS also Americanized GBBO’s format instead of embracing the original.

If the competition doesn’t waver from its original design, and keeps at least one well-known person, is that enough consistency? If Nina Garcia stays with Project Runway, is that enough? Runway has strong, beloved personalities, but it’s certainly distinct from reality shows that are synonymous with a person.

America’s Next Top Model didn’t work without Tyra Banks as its host, head judge, and divine presence worshipped by the young model contestants, so she returned after just one season away. Idol started to fall apart before Simon Cowell left, but his exit collapsed the Jenga tower. Donald Trump’s Apprentice is the only one that worked, creatively and in the ratings — though even the force of his personality, with a big assist from the editors shaping his television persona, wasn’t enough to keep its ratings from deteriorating rapidly.

Formats driven by a single person are rare, though. And a name or talent isn’t enough to bring viewers to a show. Hollywood was obsessed for years with attaching celebrities to reality TV shows, even though the evidence was clear that this didn’t have any effect on ratings. John Cena was an excellent host on his well-produced Fox competition series American Grit, yet its ratings stayed around 2 million viewers, compared to the 8 million who followed Cena on Twitter back then.

What works best are sturdy formats that can also flex. If the show isn’t molded to one person’s personality and style, a host can settle in comfortably, but also be replaced by someone who can find another comfy spot.

The Real World, the first modern reality show and the template for all that followed, died several years ago when, after suffering from MTV’s neglect, it underwent several seasons of invasive surgery that tried to transform it into a violence-saturated show like The Challenge.

But in its influential early years, The Real World established that a solid structure provided consistency enough. Every season brought a new cast, a new city, a new loft, new Ikea furniture. All that remained was the format, and those words: “seven strangers, picked to live in a house and have their lives taped — to find out what happens when people stop being polite and start getting real.”

Providing a space for people — hosts, judges, contestants, cast members — to be real: that’s enough.