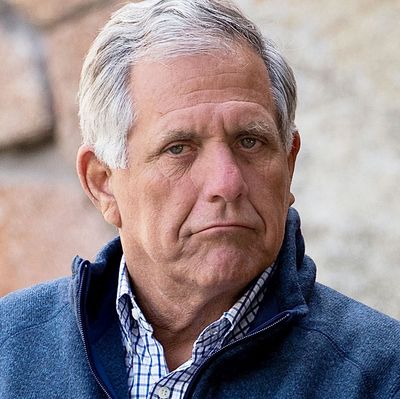

Leslie Moonves wasn’t the most powerful executive in Hollywood prior to being forced out of his role at CBS late Sunday, but he was very much one of the town’s giants. As the one-time head of the Warner Bros. TV studio, he developed the biggest comedy (Friends) and drama (ER) of the ’90s. At the turn of the century, he moved on to transform CBS — which had been struggling for years following the passing of founder William S. Paley — into the successful modern media company it is today. Moonves’s fall after three decades in the showbiz stratosphere is unquestionably a milestone moment. It also, obviously, sends a message that bad behavior has consequences in the #MeToo era, even if there will be debate over whether CBS’s board of directors acted quickly enough. But will it make much of a difference to the financial or creative landscape at CBS? At least in the near-term, probably not.

It’s not that Moonves had become irrelevant or a figurehead. Just the opposite: By all accounts, he was still an integral part of daily life at the CBS broadcast network, major assets such as Showtime, and the nascent CBS All Access streaming service. When planning for the fall season was in high gear last spring, Moonves helped determine which pilots got picked up to series or where they landed on the network’s primetime schedule. He was also the public face of the company, selling the virtues of CBS Corp. to Wall Street investors and Madison Avenue advertising agencies. These are not unimportant roles, and losing Moonves — however necessary given his actions — means losing his decades of experience and expertise.

But industry insiders I’ve spoken to in recent weeks also agree that, unlike the Weinstein Company — which completely crumbled in the wake of founder Harvey Weinstein’s unmasking — the infrastructure of CBS is strong enough to easily survive any aftershocks produced by Moonves’s departure. “Life will go on at CBS,” says Preston Beckman, a longtime programmer who competed against Moonves for years during stints at NBC and Fox. Noting the Eye Network’s “track record of stability,” he says the staffers left behind won’t have much difficulty carrying on in the absence of their long-time leader. “He’s surrounded himself with executives who’ve been around him for a long period of time,” Beckman explained. Any professional expertise Moonves “had to impart I have to believe has been absorbed [by] the executives there.” That said, Beckman also says he thinks the Moonves exit, and the self-examination it will prompt at CBS, will lead to changes not related to programming or ratings. “I have to believe that this will have a profound impact on the culture at CBS for years to come,” he said.

That’s certainly true of most of the top executives Moonves leaves behind. Joe Ianniello, who has been named interim CEO of CBS Corp., has worked at the company for nearly two decades and was Moonves’s hand-picked successor. CBS Entertainment president Kelly Kahl has spent almost his entire professional career working for Moonves, and a few of the key strategic moves often credited to Moonves — like shifting CSI to Thursdays behind Survivor — were actually the brainchild of Kahl and his team. CBS Studios chief David Stapf worked in the Warner Bros. TV PR department when Moonves ran the studio and followed him to the Eye in 1999 for a gig in programming. While all of these execs have their own brains and individual styles, they’ve worked with Moonves for so long, their tastes and creative instincts are very much in line with his. “I told someone the other day that Les could be hit by a bus … and it would be about ten years before we noticed he was gone,” one agent joked.

Of course, this scenario assumes execs such as Ianniello, Kahl, Stapf, CBS chief digital officer Jim Lanzone, Showtime president/CEO David Nevins, and CBS development chief Thom Sherman don’t follow Moonves out the door. The TV industry consensus seems to be that most of them will stay put — at least in the near-term. After all, while CBS is hardly immune to the struggles facing all traditional media companies right now, the company is doing reasonably well. The CBS network draws more regular season viewers than any other broadcast or cable outlet, and Showtime is adding subscribers and making more original programs than ever. CBS All Access is also off to a decent start, though it needs to add a lot more subscribers soon to be a viable money-maker. Moonves’s exit by itself probably won’t be reason enough for other execs to bolt. (Most are also under long-term contracts which would make it difficult for them to quit.)

It’s also worth remembering that for all of his abilities as a programmer and executive, part of Moonves’s power derived from the mythology which built up around him. He was the master salesman during the upfront advertising season, the unofficial spokesman for the power of broadcasting, the man with the golden gut when it came to picking shows and stars — or so the legend of Moonves insisted. And to a degree, Moonves was all of those things (along with, per mounting allegations, a sexual predator). But much the way we in the media overhyped the late, great NBC exec Brandon Tartikoff, Moonves has benefited from the tendency (by both reporters and corporate boards) to put too much value in the Great Man theory of history. In fact, whatever success CBS has had the past two decades was not the result of a single designer suit-clad superhero picking hit shows and negotiating the right talent deals. A small army of Eye execs past and present were instrumental in shaping the network, both for good (Everybody Loves Raymond, NCIS, The Big Bang Theory) and ill (Kevin Can Wait). Plus, as with any network or streaming service, the real drivers of success at CBS have been the show creators and stars who make hit programs. CBS won’t be the same place without Moonves, but like Apple after Steve Jobs, it won’t collapse either. It’s telling that late last week, as multiple news outlets reported Moonves was in settlement talks, CBS’s stock price actually went up.

Still, there are a few wildcards that could disrupt the Eye’s post-Moonves stability. It’s possible that, without Moonves around, the chemistry inside CBS Corp. could shift. Most of the top managers at the company seem to get along fine, but it would be naïve to assume the power vacuum created by Moonves’s exit won’t have any consequences. Execs who now seem likely to stay put could try to walk if, for example, Ianniello began micromanaging a particular division or otherwise rankled his new underlings. (This is not to suggest such an outcome is likely: By all accounts, Ianniello is well-liked and respected within CBS Corp.) It’s also quite possible the CBS board will decide to make a clean break from the Moonves era and bring in someone other than Ianniello to serve as permanent CEO, prompting further departures. What’s more, we don’t know yet what the independent investigations into the workplace culture at CBS will yield, or if any other senior execs will be found to have engaged in abuse, assault, or other inappropriate behavior. As it is, 60 Minutes executive producer Jeff Fager, also named in the New Yorker’s two stories about the company, seems a prime candidate to resign or be fired.

Finally, while the settlement announced Sunday says that CBS and Viacom will remain separate for at least two years, that doesn’t mean other mergers might not happen. Indeed, it’s quite possible that over the next year or two, CBS will end up buying (or being absorbed by) another major company as it seeks the scale necessary to take on rivals such as Netflix, Amazon, Comcast, and the soon-to-be-merged Disney/20th Century Fox. Depending on who buys whom, big changes could yet be coming to CBS. And like all companies whose main income source is linear television, there are plenty of plausible scenarios under which things at CBS go south, and quickly. But if they do, it won’t be because the CBS board of directors got rid of Leslie Moonves.