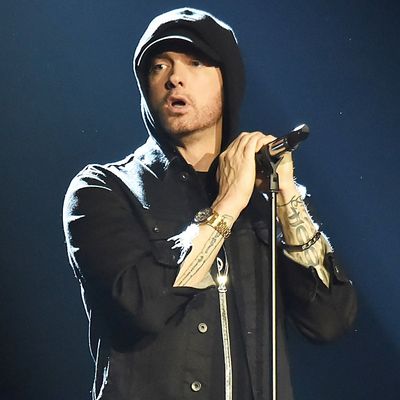

To a certain brand of existential crank, Eminem albums were once affirmations that it was okay to be angry and defiant. For a time, as the cool-but-not-that-cool ’90s bucked to the culturally and politically conservative strictures of the Bush administration, the outlook felt vital. Squeaky clean, cookie-cutter pop acts personified the homogenization of the American teenager, the logic went. In the beginning, Eminem was defined as much by the irony of a scrawny midwestern latchkey kid’s unprecedented success in rap as he was by the row it created to have a razor-sharp battle rapper holding court with the pop elder statesmen and well-groomed, media-trained former child stars dominating the charts at the end of the century. If you were a smart-ass, Em was your man on the inside. He made the machinery of celebrity look slipshod and silly. His craft was a fruit of a decade of practice, but on television, he never seemed very rehearsed. The records took like wildfires, an ecosystem’s natural act of destructive course correction. The ascendant rap god, born Marshall Mathers, was destroying and rebuilding pop as we knew it.

Nearly 20 years after the Slim Shady LP, Eminem has come to embody the very Establishment he once worked to overthrow. Rap fans who came of age during the crunk, snap, and trap eras that flourished during the Detroit MC’s five-year sobriety journey and musical hiatus post-Encore don’t subscribe to the idea that a rapper needs to be the sharpest rhymer to sell a song. As southern rap and SoundCloud rap get more established on the charts, Eminem gets more pedantic about why he believes those artists are doing their jobs wrong. He’s painting himself into a corner not because there isn’t ample space for lurid, technical raps in the garden of hip-hop microgenres presently coexisting in the culture (there’s plenty!), or because he’s closer to 50 than to 40 now (consider the 47-year-old Jay-Z’s beloved 4:44, or the enduring appreciation of Diddy, Will Smith, and Missy Elliott), but because he has planted himself resolutely on the side of an age gap that always loses. You can’t unring a bell; Eminem won’t un-“mumble” rap. What he will eventually do is pick enough one-sided fights with enough young and unbothered stars to sour the case for himself, and from the title to the lyrics, his new album Kamikaze makes this its express purpose.

In the twilight of the world-beating trilogy of Slim Shady LP, Marshall Mathers LP, and The Eminem Show, are two kinds of Eminem albums: the ones where he resists the formulaic insolence of his albums and tries something different, and the ones where he realizes the changes didn’t stick and returns to form. Encore begat Relapse. Relapse begat Recovery. Recovery begat Marshall Mathers LP 2. December’s Revival was a risky gesture, a political line in the sand where the rapper made a public show of inviting the Trump supporters in his fan base to scram. It was a bold gesture for a rapper with a lot of fans who seem to only dabble in rap when he’s selling them something new. Peppering Revival with vocals from popular singers seemed like a conscious decision to offset the album’s political overtures with hooks that would buoy the singles at radio. This choice was a matter of some consternation among fans, who took one look at the Ed Sheeran, Alicia Keys, Pink, and Skylar Grey guest spots in the track listing and floated a conspiracy theory that Revival was the R&B half of a double album whose forthcoming second half would call in all of the hip-hop heavyweights Revival appeared to lack. In its first seven days, the album pulled in less than half of what Marshall Mathers LP 2 did in the same space. It is the first Eminem studio album since his 1996 independent debut album Infinite to fail to reach platinum sales certification.

Kamikaze reckons all of this is our fault. From the first verse of the opener “The Ringer,” the new album is a flurry of daggers for critics he swears don’t get it, fans he accuses of forsaking real talent for vapid drug rap, and younger rappers he believes are selling substance without style. It’s Macbeth, pursuit of power through a hail of bloodshed utterly lacking in considerations for the consequences. He’s sharp. The rhymes are never less than dizzyingly dense. “Like a wedding band, you gotta be diamond to even climb in the ring,” he blurts out in “The Greatest.” “An anomaly, I’m Muhammad Ali.” But virtuosity can be soulless. Em is an assassin with flows and cadences, but over the last few albums, his choice of subject matter sometimes left much to be desired. There’s no glory in copping to hating everything on the radio. Realizing you could have worked a little harder on the job last year isn’t an epiphany. People everywhere do both every day. Eminem is so prideful he mistakes simple candor for depth; “Stepping Stones,” Kamikaze’s heaviest song, apologizes to his old Detroit clique D12 for not doing more for their careers.

It’s telling that most of Kamikaze’s biggest drama dates back years and decades. “Not Alike” antagonizes the Cleveland rapper Machine Gun Kelly for tweeting that Em’s daughter Hailie Jade was “hot as fuck” in 2012. (She was 17 at the time.) “Fall” snaps at Earl Sweatshirt for telling Spin, “If you still follow Eminem, you drink way too much Mountain Dew and probably need to, like, come home from the army” in 2015 and sends a censored gay slur on Tyler, the Creator for insinuating that “Walk on Water” sucked last year. The lateness of these quips suggests that retribution is Kamikaze’s entire mission statement, but like the doomed fighter jets that gave the album its name, Em is hurting himself with every collision. Bleeping the slur against Tyler suggests that he knows he shouldn’t be doing it, and even Bon Iver, who sings the song’s chorus, hates it. It’s embarrassing behavior, both using Tyler’s raps about same-sex relationships against him and trying to soften the blow through edits, like he’s aware of a cultural mandate he can’t be bothered to honor. Shit or get off the pot. Kicking up a fuss about Earl, MGK, and the laundry list of young artists who catch hell in “The Ringer” is tacit admission that Eminem believed he was too big of a name to respond to those attacks last album, but he isn’t now.

Eminem’s crabby criticisms of other artists are unfortunate this year because what the guy needs most right now is a jolt of energy from someone who approaches words differently. His albums have always been a little too insular for their own good, but since at least MMLP2, his verses have grown too dense and cerebral to breathe and swing, and his hooks are often too jerky, rhythmically or melodically, to be catchy. Em has addressed the latter issue by calling in triumphant vocals from Pink, Rihanna, Beyoncé, and others, but that created its own problem, because now, a rapper who made his name skewering all the big pop singers knows better than to try it with them, since in the last four years, he has rarely scored a hit single without them. In excellent collaborations with other rappers, like Big Sean’s “No Favors” and the Busta Rhymes tête-à-tête “Calm Down,” Eminem has proven he’s still a vital sparring partner. When Kamikaze invites the Massachusetts rapper Joyner Lucas to guest on “Lucky You,” it scores its first earworm. The methodical Jessie Reyez raps on “Nice Guy” nudge the marquee artist toward pointed story raps that revisit his old glory, when songs gripped with emotion and honesty, not just a barrage of internal rhymes. The melodic relationship raps on the back end of “Normal” pose the question of how much better this half of Eminem’s decade could’ve gone had he poured himself into collaborations with guys like Drake and Future instead of writing their entire wing of rap off as heralds of some coming real hip-hop apocalypse.

Kamikaze’s concern with counteracting the major faults of the last Eminem album makes for less of a like-minded companion album than a fussy, defiant little brother to the (comparatively, somewhat) more straight-laced Revival. It’s 30 minutes shorter, for starters, and its collaborations don’t feel like cash grabs. There is 100 percent less Ed Sheeran. It’s not trying to force woke political Eminem on us or straining to juggle its civic mindfulness alongside a desire to cram all of George Carlin’s seven dirty words into every song. It’s a better, leaner album, but it could’ve been better and leaner without embarrassing moments like stopping “The Greatest” to yell “Revival didn’t go viral!” or quipping “Let’s sleep on it like they did Revival” in “Normal.” Blaming the failure of a shaky album on the fans, the critics, the teens, and the current state of hip-hop — anyone but yourself — isn’t growth. First week sales aren’t progress reports. You can be great without being ubiquitous.

But does Eminem really hate playing ball in the modern rap mainstream? He runs a satellite radio station and a record label populated by young, hungry rhymers like Boogie, Conway, and Westside Gunn. He has relationships with wizened beatmakers like Alchemist and Scram Jones. Great rappers still love sparring with him. Imagine Eminem doing intricate buddy caper raps with Roc Marciano or geeking out about exotic snacks with Action Bronson. He’s rich and connected enough to disappear into the wigged-out corners of his mind, as rap elders like Raekwon and Prodigy did on post-peak back-to-basics albums like Only Built 4 Cuban Linx 2 and Return of the Mac. What Eminem really wants to keep selling us is essentially the same product and enjoying the same sales and accolades, and it’s just too far into the game to believe this is how careers work, to be this confused about why people aren’t scooping up your albums. What happens if Kamikaze doesn’t outsell Revival? Who’ll be to blame then?