In high school, Michael Urie used to do an exaggerated “gay voice” as a joke. It was sibilant and effeminate, but in suburban Plano, Texas, in the early ’90s, where nobody would admit to knowing anyone who was gay, it got laughs. Urie was good at the gay voice — it was “really an extension of myself, I realize now” — and he liked the attention it got him, until one popular girl laughed too hard and told him, “You’re too good at that.” “It wasn’t an insult,” Urie remembers, but a sort of warning: “You can do that, and you can be really good at that, as long as you’re straight.”

Urie, now 38 and in rehearsals for the Broadway revival of the landmark gay drama Torch Song, tells me the story over a pitcher of Blue Moon at a beer garden in Astoria. He has an upbeat energy that recalls a silent-film star and an ability to make things funny even when they’re not. We’d made plans to dance at the so-called silent disco the beer garden will host later, where music is played only through headphones. But first we’re here to discuss a character who never would have listened to that girl in class.

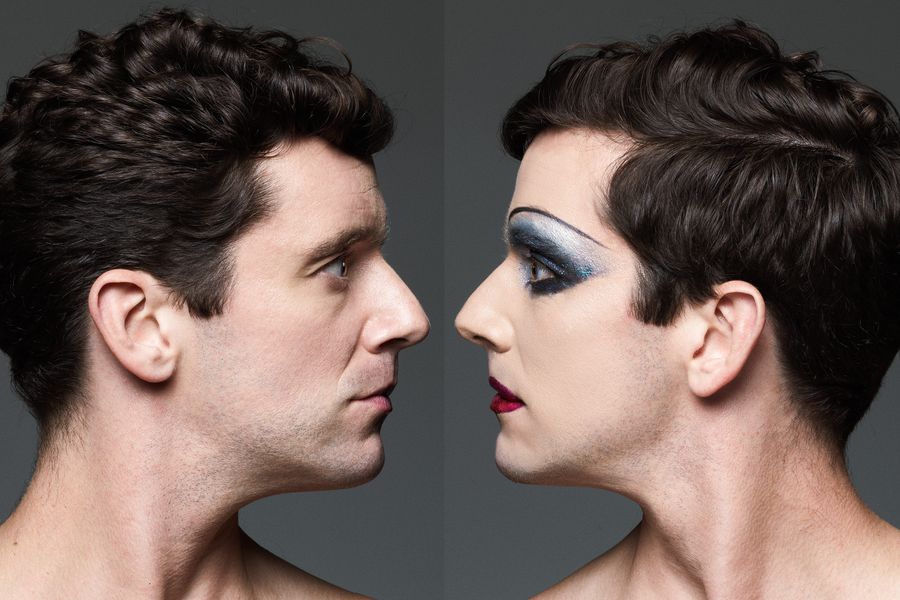

Torch Song is a condensed version of Harvey Fierstein’s trilogy about a down-on-his-luck drag queen named Arnold (originally played by Fierstein) that first opened on Broadway in 1982. Arnold is effeminate and unapologetic — he demands to be loved, to have his own family, to wear bunny slippers whenever he likes. Written before the AIDS crisis came into view, Torch Song is both a memory of a time gone by and a vision of an alternate future, where the kind of love Arnold imagines might be possible. “There’s something very therapeutic for me playing Arnold, who has very little shame,” Urie says.

Though he’s made his career playing gay men, Urie admits he still contends with that kind of shame. When he tested for the role of the bitchy assistant Marc St. James on ABC’s Ugly Betty a few years out of Juilliard, “I didn’t walk into the audition as a known gay person,” he says. (That is, he was out to his friends but without a name of any kind in the industry.) “So I went for it and played effeminate and camp. I wonder if I had been known as gay, if I would have felt so comfortable.”

For his first few years on Ugly Betty, Urie stayed in a sort of glass closet, avoiding direct questions about his sexuality but never denying it and appearing on red carpets with girls who were friends. “There was this idea that when the show was over, you wanted to be able to get something different,” Urie says. But while he’d worried that he’d be stuck playing campy gay villains, he’d forgotten there weren’t many of those on TV in the first place. After Ugly Betty was canceled in 2010, he didn’t get many offers. If a show was looking for someone like Marc St. James, it didn’t want Urie; it wanted “the next me,” he says.

Urie’s perspective on coming out had already changed when he booked a role in The Temperamentals, a play about the proto–gay rights Mattachine Society in the 1950s. He got good reviews, and Urie realized that playing gay parts wasn’t going to pigeonhole him as much as he’d thought. “I’m playing a totally different gay guy,” he says, which convinced him he was “going to be all right letting people in on the truth of who I am.”

Post-Betty, apart from a few sporadic TV appearances — he pops up on Younger and starred in a 2012 sitcom, Partners, that was canceled halfway through its first season — Urie has focused mainly on theater. He workshopped the 2011 revival of How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying but lost his part before the show moved to Broadway when a rights owner decided he was the wrong fit. “At the time, it was totally devastating,” he says, but with his schedule cleared, he booked a role in the 2011 Off Broadway revival of Angels in America; directed a film, He’s Way More Famous Than You, starring his partner, Ryan Spahn; and eventually joined the same production of How to Succeed as a replacement.

Soon after was the one-man show Buyer & Cellar, written by Jonathan Tolins, in which Urie played a struggling actor hired to organize the mall in Barbra Streisand’s basement. The play made him a theater star, winning him awards in New York. He toured the country with Buyer & Cellar, and says he felt sticking with it through its run “gave me credibility.” The fact Urie could do an accurate impersonation of Streisand helped, too. “I don’t think they ever would have let me be Harvey Fierstein,” Urie says, “if I hadn’t been Barbra Streisand.”

Torch Song is the first time Urie’s opened a show on Broadway. “It’s an emotional play, a gay play, a language play, a comedy, a drama,” Urie says. “It feels like everything that I’ve learned up till now, I need.” The show has Fierstein’s cred, and an Oscar and Tony winner, Mercedes Ruehl, as Arnold’s mother, but Urie knows it’s still a gamble. “It is pretty exciting that they picked a guy from the theater,” he says, “who’s been hoofing it onstage and in television but is not a movie star.”

Urie also recently directed his friend Drew Droege’s one-man show, Bright Colors and Bold Patterns. In that, Droege plays Gerry, a bitter single gay man at a friend’s gay wedding, resentful of their cheerful adoption of conventional straight life. In Urie’s mind, “this guy might be Arnold on another path,” facing the same questions with different answers. They’re questions Urie is still considering. He and Spahn have dated for a decade, but marriage isn’t in the cards. “When it became possible, it wasn’t something we were eager to do,” he says, though he leaves open the possibility that the pair might race to the courthouse at any moment.

At this point, the beer garden is full of people lining up for the dance party. Urie’s invited a few friends along, including Spahn, and we go to pick up our headphones. Urie’s wearing a Beto O’Rourke T-shirt, and as he pours his friends beers, he catches them up on the night’s Texas Senate debate.

As we all take to the dance floor, singing to N’Sync and Earth, Wind & Fire, I think about something Urie said earlier, about wishing he could sit Gerry from Bright Colors down with Arnold from Torch Song, along with his characters from the plays Homos and The Temperamentals — you could throw in the ones from Ugly Betty and Buyer & Cellar, too — and “tell them that somebody was told, ‘You’ll be typecast as gay.’ As if there’s only one kind of gay person?”

*This article appears in the October 1, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!