“There aren’t that many times in life when you’re absolutely free” is how Studio 54 co-founder Ian Schrager describes the notorious nightclub he ran for 33 hedonistic and controversial months in the late 1970s. The venue was legendary even in its own time — New York Magazine, for one, couldn’t stop running cover stories about it — but now it’s passed into the realm of myth. And depending on who’s doing the mythologizing, it’s either a cautionary tale of excess and criminality, or a dream vision of a fleeting moment when you could be anybody (and do anything) you wanted.

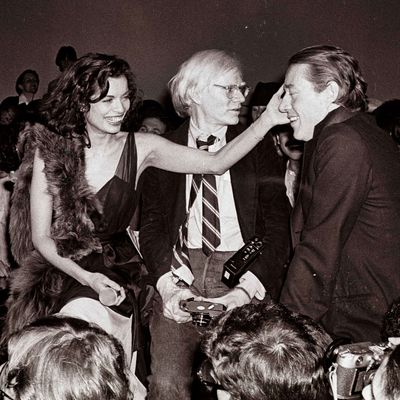

Matt Tyrnauer’s swift, entertaining documentary largely belongs to the latter camp. It has the benefit of access to Schrager himself, who founded the club alongside the late Steve Rubell, who died of complications from AIDS in 1989. As Schrager and other surviving regulars tell their stories, the screen lights up with iconic archival photos and footage from the club itself. And it does seem like a fantastical dream, all flashing lights and throbbing bodies — a whirlwind of color and motion and sensuality, with a regular parade of familiar faces: Liza and Cher and Warhol and Capote and Baryshnikov and multiple Jaggers. Forget the cocaine, the real drug Studio 54 peddled may have been celebrity: a chance to be next to, and one of, the beautiful people. And you watch Studio 54 wanting very much to be a part of this world. It looks like the greatest party you weren’t invited to.

As the film makes clear, the club was also an oasis for many who were outcasts elsewhere. Once within Studio 54’s well-guarded gates, partygoers found themselves in a world where anything was possible, maybe even encouraged: Men could kiss men, women could kiss women, and trans people could be themselves — all this at a time when the streets outside were boiling over with homophobia and violence. “When you dance here, you’re free,” we see a fresh-faced Michael Jackson say in a TV interview from the time. “You just dance with whoever you want.”

But most of New York couldn’t get into the club. They weren’t good-looking, or fashionable, or famous enough. For all that it may have meant to the regulars, Studio 54’s true power lay in what it projected to the rest of the world. And its downfall coincided with a growing resentment in the country at large, one that led to a backlash against disco itself. As musician Nile Rodgers puts it eloquently and chillingly in one interview, over images of the 1979 Disco Demolition at Comiskey Park, where a local DJ blew up crates of disco records: “Imagine what Studio 54 and disco life looked like to somebody in the Midwest who’d lost their job, which was never coming back. You blame it on other people — on gay people, black people, and women.”

Of course, Studio 54’s owners admitted that they themselves probably couldn’t have gotten in either. Two lower-middle-class kids from Brooklyn, Schrager and Rubell made for a complementary team: The former was introverted and businesslike, while the latter was an outgoing party animal. A third, “silent partner,” Jack Dushey, handled much of the financing for the club, and it’s interesting to hear him speak in this film, talking about the various hustles involved in the venue’s creation and success. Schrager and Rubell would eventually be imprisoned for tax evasion. The film, to its credit, makes clear that they didn’t just skim a little off the top like most crooked bosses; they stashed away something like $2 to 3 million in a very short period of time, almost as if they knew their operation wasn’t long for this world. (One of the film’s more animated interviewees is Peter Sudler, the prosecutor in the Studio 54 case, who still expresses bewilderment at the brazenness of this grift.)

But Tyrnauer isn’t interested in going over old misdeeds. He’s more focused on the friendship between the club’s creators. Despite their differences of personality, Rubell and Schrager were extremely close, and continued to partner together after they left prison, as they eventually got into the luxury hotel business. While the depiction of these two men’s relationship — their love and loyalty for one another — is touching, Tyrnauer finds himself in awkward territory when later scenes wind up dutifully cataloguing all the great hotels that Schrager has opened in the ensuing years. At some point, you may wonder if you’ve been watching branded content from Ian Schrager’s Public Hotels all along.

Maybe the point here is that the spirit of Studio 54 has somehow mutated and made it into these slickly designed guest-room experiences all around the world; Schrager himself certainly seems to think so. But what does that say about the times we live in, that a supposed beacon of freedom and possibility, of unruly and joyful transgression, has become, ultimately, just another brand of luxury product?