Like everyone in Baltimore, I have a John Waters story. I’m 15 and my parents think I’m at a girlfriend’s house, not with an older boy, riding on the back of his motorcycle. Seeing giant spotlights and choreographed dancing in the middle of nowhere, we stop for a closer look. We crawl under chain-link fences, staying for hours to watch a camera crew film take after take. Only later did I realize we had stumbled onto the set of Cry-Baby, Waters’s eighth feature film, starring Johnny Depp, Ricki Lake, Iggy Pop, and Traci Lords. For me, the memory represents the sense of dramatic possibility that continues to permeate Baltimore; I never know what magical spectacle awaits me and whether a 27-year-old Depp might, at least in theory, be lurking around the corner.

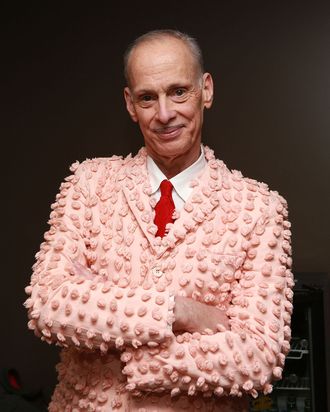

John Waters is one of Baltimore’s greatest cultural exports. If you know next to nothing about Baltimore, you probably learned it from watching one of his films — all of which have been set in the city in which he grew up, and still lives. Whether intentionally or as a byproduct of his films, the Prince of Puke has become a pillar of the city’s creative community, inspiring lawns full of plastic pink flamingos as well as a certain clever insouciance.

What many Hairspray fans don’t realize is, over the past few decades, Waters has transitioned his creative energies from filmmaking into live performances, writing books, and making visual art. In 1992, he took a grainy still from his early film, Multiple Maniacs, of its deceased star, Divine, and titled it Divine in Ecstacy. Since then, he has mined the history of film and popular culture into photography, video, sculpture, and sound works that veer from the absurd to reverent. He shows with Marianne Boesky in New York, and is a discerning collector and supporter of young artists as well.

At 72, Waters remains an enigmatic force in Baltimore. Even as the city which inspired him has its ups and downs (the city’s other defining cultural export, after all, is The Wire), he’s inspired generations of creative insurgents to envision Baltimore as the perfect setting to realize their DIY dreams. And since, as he put it recently, it remains “still cheap enough to have a Bohemia,” artists can afford to live and work here, and it sustains a lively art scene. The Baltimore Museum of Art is currently staging a retrospective of the Pope of Trash’s artwork titled “Indecent Exposure,” which puts a range of his transgressive daring on display. On the occasion of the exhibition, I asked six Baltimore-based artists to consider the ways he has influenced their work.

Joyce J. Scott

“John’s audacity to make his own rules and succeed continues to inspire me,” says artist and West Baltimore native Joyce J. Scott. The city boasts just a handful of MacArthur geniuses and none is as badass as Scott, who employs traditional craftwork like beading, blown glass, and weaving to depict racial and sexual violence, pairing trauma with humor and stunning visual beauty. Her subversive approach, combined with impressive technical prowess, results in a visual complexity that pops with the shock of a punch in the face. “When they look at my work, I always want people to say, ‘What the fuck, Joyce?’” says Scott. “I want people to always be like, ‘Daaaaaaam’ with all of the As.” You can see her bold sculptures at the solo exhibition “What Next and Why Not” at Peter Blum’s lower Manhattan gallery on view through November 10.

TT the Artist

“I love the way John Waters took race and gender and put it into a form everyone could understand,” says rapper TT the Artist, citing Waters’s 1988 film Hairspray as an inspiration. The Baltimore transplant moved from Florida in 2002 to attend the Maryland Institute for College of Art (MICA). Coming from a strict religious upbringing, Baltimore was a whole new world, and here TT discovered an unabashedly sexual persona. Her lyrics like, “Don’t want no car/ Don’t want no cash / Don’t want no date / I just want my pussy ate” have found her fans in Diplo, J.Lo, and Issae Rae, who’s used the artist’s songs in every season of her HBO show Insecure. Now, TT’s expanding her practice to include filmmaking, with a documentary about Baltimore club music due out in spring 2019. “As a filmmaker,” TT explains, “I love Waters’s color palette because it’s whimsical and surreal. I want my films and music videos to toggle between real life and role playing, [realizing that] combination of fantasy and reality.”

Wickerham & Lomax (Dan Wickerham and Malcolm Lomax)

“I’m still shocked how often people identify with the anarchy of Waters’s characters, but not their morality,” says Dan Wickerham, of Wickerham & Lomax, a creative partnership whose work mines Baltimore’s unique history of queer club culture through spectacle-driven installations. For the past decade, Wickerham & Lomax have consistently puzzled audiences with over-the-top, media-savvy projects. For instance, Girth Proof cast participants from Craigslist and rendered them as CGI bulked-up event planners while BOY’Dega set a television series inside a traditional hair salon merged with a CIA office and Vogue fashion closet. “Baltimore has had a huge influence on our work because we think of the whole city as material,” says Wickerham. “We are specifically interested in how the idea of Baltimore has been exported, which John had a huge part in. We insert ourselves into the city’s myths in hopes of stretching them into a more complicated rendering of how we experience it.” Currently the duo is busy preparing for a 2019 exhibit at the New York gallery American Medium and running Diskobar, an actual bar in Baltimore open six nights a week.

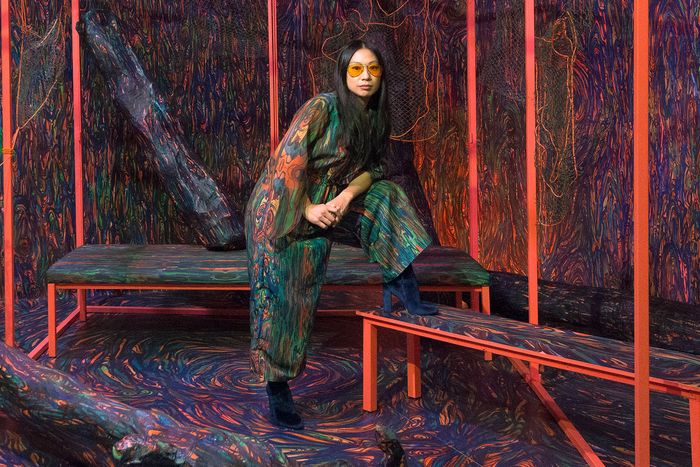

Phaan Howng

“Hairspray (the original, not the remake, never the remake) is my favorite JW movie,” says Phaan Howng, the installation artist who just finished “The Succession of Nature,” a yearlong exhibition at the BMA, which envisioned a future Earth where plants have triumphed over humans while functioning like a dystopian dance party. Howng hypothesizes that Hairspray might be partly responsible for this thread of dance in her work. The artist moved to Baltimore in 2013 to attend MICA for graduate school and cites the city’s social and environmental issues, including the decay of the built environment, as inspiration for her work. Coincidentally, Howng’s exhibition at the BMA ended the same weekend that Waters’s retrospective opened. She recounts that she was channeling Waters with her bombastic closing act, the “End of Days Spectacular Spectacular,” featuring a parade, marching band, traditional Chinese dragon dancers, hecklers, and a dance party on the front museum steps. “I was surprised he wasn’t planning a similar spectacle,” says Howng. “Since he wasn’t, I figured I’d better fucking bring it, à la Hairspray dance competition drama.”

Michael Farley

“I distinctly remember seeing Female Trouble as a teenager and how much it changed my life,” says artist Michael Farley who grew up in Baltimore’s suburbs. “At the time, I was going to a godawful conservative Catholic school, so discovering John Waters was life-changing. Here were these angry queer people with Baltimore accents who hated the suburbs and wore whatever the fuck they wanted! At the time, it felt like I had discovered this secret alternate universe made just for me.” Today Farley’s wide-reaching body of work is knit together by a camp sensibility, from his drag persona Ellen Degenerate to a faux-Scandinavian pavilion, like the kind you’d find at the World’s Fair, referencing both Ikea and Norwegian black metal through furniture dyed with real blood. Farley, who currently splits his time between Baltimore and Mexico City, recently completed a “Waters-esque” music video for Mexican electronic musician, the TBD, full of sex shops and cruising leather daddies.

Labbodies (Ada Pinkston and Hoesy Corona)

“John Waters made me realize that it’s possible to make a body of work that is simultaneously liberating and uncomfortable to look at,” says Ada Pinkston, who co-founded Labbodies with fellow artist Hoesy Corona back in 2014. A performance and curatorial project focused around championing women and queer artists of color in museums, galleries, and public spaces, their activities include hosting an annual performance review, which brings together local and visiting artists for a weekend where you’re just as likely to attend a séance as participate in a punk-rock dance party. Labbodies, which had its humble beginnings at the infamous live-work loft, the Copycat Building, embraces a DIY ethos that is pervasive across Baltimore’s creative landscape, channeling Waters’s “fuck permission” mentality. Pinkston loves running into Waters at events and bars in Baltimore. “It’s fun to party with a legend in such a relaxed way,” she says, “to be able to talk to him, to get a head nod, which I read as, ‘It’s good to see that the next generation is fucking shit up!’”