Every generation gets the stars it deserves. The ’60s sprouted psychedelic stoners and mystics in direct correlation to the G-rated wholesomeness of mainstream culture at the time. The coked-up lawyers and accountants of the ’80s felt a kinship to normie pop kings like Lionel Richie, Huey Lewis, and Phil Collins. This decade is spawning wild boys with terrible court cases, I think, because of a faulty idea that floated in the twilight of the Obama years that culture had gotten too considerate and politically correct for comfort and because the sociopolitical response to that lie has been to redistribute power and influence to a rogue’s gallery of Earth’s most pigheaded, ghoulish characters. Rudeness, egotism, and bottomless irony are threaded in the roots of this society. What’s growing as a result should surprise no one.

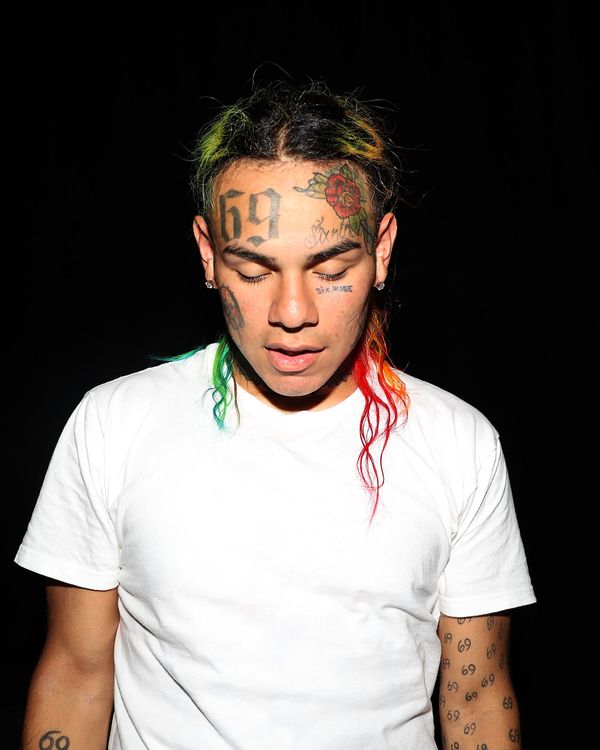

Tekashi 6ix9ine is a natural-born Instagram-generation superstar because he’s crude, brutal, funny, and colorful. Rap is a smart career path for personalities like these because hip-hop fans value cocky, gauche, uncompromising characters. (Rap also has a low barrier of entry, low overhead, and quick turnaround times right now. You can’t up and start acting or painting and have a hit in a week. You can bark your way into internet renown for a verse you wrote in half an hour.) They resonate because they dare to say and do what most of us can’t or won’t. Tekashi’s success as a rapper is more a function of single-minded, limitless arrogance than any natural ability to rhyme words. The music is an extension of the videos. It pops because it’s wild, flagrant, and disrespectful. Really, “Gummo” and the like are cartoonish comedy performances. Like a rap Road Runner, Tekashi spent the year zipping around the country outsmarting his enemies seemingly without consequence, enjoying a reputation as a bully and a badass as he succeeded in landing a series of increasingly worrisome threats, stunts, and insults.

Now that he’s in jail facing a possible life sentence for dealings with gang members that the FBI suggests were itching to take him out, Tekashi, born Daniel Hernandez, wants us to believe that he was just playing a character the whole time, that 6ix9ine is a performance and a fabrication, that Daniel is the good guy handing out money to families and hugs to young fans. It’s eerily close to the statement he gave to police to explain the sexual misconduct with a minor charge he’d accept the blame for after appearing in a video of an underage girl performing sex acts on other men: “I was doing it for my image.” 6ix9ine’s court cases present a very postmodern conundrum. Are we to believe he’s the vindictive, gang-affiliated millionaire bully he plays in his art and on the ‘gram, the one the platter of racketeering charges he was served this month appears to corroborate, or are we supposed to buy the other tune he’s singing about his tough talk being an act of pure provocation, like the “69” tattoos that cover his body? Is it possible to thirst for street cred so hotly that you stumble into the dark power you seek, like Robert Johnson cutting a deal with the devil at a Mississippi crossroads? Does it matter what Tekashi’s thinking is if it instigated real violence?

6ix9ine’s debut studio album Dummy Boy is light on answers. (The only real acknowledgment of things going awry is the big deal made about not shouting out the rapper’s former affiliates in the Tr3yway set.) It’s an insane moment; rap debut albums are usually fanfares trumpeting newly minted stardom, but this one hit the public via a leak while the marquee artist awaits a September 2019 trial where he faces 32 years to life in prison. Turmoil in the wake of getting kidnapped, robbed, and shot at over the last year hasn’t darkened the texture of the music, the way Los Angeles rapper 03 Greedo’s God Level detailed his fears and worries as he prepared to serve hard time for a firearm charge earlier this year. Dummy Boy deals in the same unrepentant goon talk as this past winter’s Day69 mixtape. The difference here is window dressing. A-list guests and forays into R&B duets and Latin trap tunes are meant to showcase Tekashi’s range, but bigger productions and veteran voices have the inverse effect. He gets creamed by a guest on nearly every song, and his singing is so thin and featherweight that it makes you miss the shouting.

There’s a certain evil charm to trap growlers like “Stoopid” and “Tati,” but even those are cannibalizing flows and jokes from older 6ix9ine songs. The sense that the guests are here because this is where the most people’s eyes and ears are going to be this month is hard to shake. The collaborations are never effortless; a guest shows up with a strong contribution, and Tekashi follows the leader. Nicki Minaj packs so much personality into “Fefe” that it’s easy to forget whose single it is. Nicki and Kanye West run off with “Mama.” Puerto Rican rapper, singer, and provocateur Anuel AA shines on “Mala” and “Bebe” — two songs with identical woman-as-demon metaphors situated back to back in Dummy Boy’s track list — while 6ix9ine struggles to match his partner’s command of the notes and timing. Tekashi’s trying to branch out, but too much input from too many stars with a better handle on their voices makes the marquee artist here feel small.

Dummy Boy isn’t a total wash. It is amateurish and two-dimensional. Tekashi does best when he applies himself. The Gunna collaboration “Feefa” gets both rappers thinking about mortality over a beautifully somber guitar lick. “Waka” smartly pairs the jittery energy of a good hook from a Boogie wit da Hoodie with 6ix9ine’s bulldog bark. Dummy Boy would have benefited greatly from more of this and less colossally ill-conceived ideas like “Kanga,” where 6ix9ine does a keen Fatman Scoop impression, and Ye shows up to a song about sex to grouse about the press. But like much of the crop of big-deal rap albums that created more smoke than fire this year, this album is an exercise in self-preservation, not in the advancement of craft. Dummy Boy doesn’t need to be great. It’s snack food. It’s Hot Cheetos, intense and intriguing until it wears you out, and you move on to something else. That’s how we consume rap now. We’re like spectators bottlenecking around a highway accident. Stop, stare, advance. Small wonder that the major-label rap music of the streaming era is going the same route as the listenership. They get away with everything we’re willing to put up with, though. That’s the story here, isn’t it?