Hypothetical scenario: You’re an unsigned and decidedly underdog band that’s been picked up by a major record label. It’s taking a chance on you, offering to roll the dice with the hopes of making you the next big thing. After a couple of solid albums and modest-but-sustainable sales, you’re set to release your career-defining masterpiece — one of the best records of the decade. Despite talking a big game promotion-wise, your label drops the ball at the 11th hour, the album peaks at 140 on the Billboard charts, and a year later you’re off its roster. The ironic M. Night Shyamalan twist: It appears this whole time you were the one rolling the dice.

Welcome to the 20th anniversary of this hypothetical scenario becoming demonstrably non-hypothetical for Illinois alt-rockers Local H. And after a couple decades of hindsight, the lesson to be learned is that talent, grit, and a big ol’ record deal aren’t always enough to make the rock and roll dream a reality. Let’s allow the band to count the ways.

First a quick remedial session. If you’re not familiar with Local H, it’s because you’re wrong about not being familiar with Local H. You’ve likely heard their 1996 single “Eddie Vedder,” which poses the age-old relationship question, “If I was Eddie Vedder, would you like me any better?” If not, you’ve definitely heard the angst-riddled “Bound for the Floor,” casually known to many listeners at “The Copacetic Song.” Otherwise, there’s still a decent chance you’ve come across one of Local H’s myriad tunes over the past 23 years, including their most recent single, “Innocents,” which features one Mr. Michael Shannon in the music video.

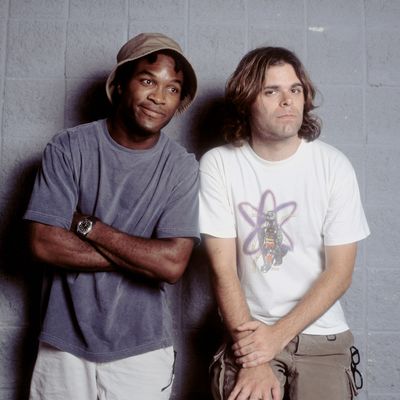

In 1994, Local H put out a bunch of feelers in search of a record deal. They were a two-piece band, having long foregone the need for a bassist by adding customized low-register pickups to a bevy of six-string guitars. Drummer Joe Daniels was an absolute monster on the drums, and front man Scott Lucas was no slouch on guitar, had a hell of a voice, and rocked harder by 9 a.m. than most of us rocked all day, but their demo was noisy, aggressive, and pretty unpolished. And they were biracial (one white guy, one black dude), which made them difficult to categorize back in the reductive ’90s.

Nonetheless, harder-edged alt-rock was flying high in ’94, with many labels seeking out the next Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Stone Temple Pilots, or Soundgarden. Polydor A&R rep Joe Bosso took a shine to the Local H boys and saw their potential. Coincidentally, Polydor was in the process of merging with Island Records. Soon afterward, Lucas and Daniels found themselves sharing a label with U2, the biggest rock band in the world. Unlike U2, Local H still had a few ladder rungs to climb to reach superstardom. Their debut, Ham Fisted, hit stores in January 1995. Island released “Cynic” and “Mayonnaise and Malaise” as singles, and as catchy as they were, the album failed to chart.

Lucas wasn’t shocked by the lack of fanfare. “For the most part, we were trying to scream and bang our instruments as much as we could,” he tells Vulture. “That was our sound at the time, so it would have been almost impossible for us to make a record that would have sold a lot of copies, if Island had expected something like that.”

Bosso, who served not just as an A&R rep but as the band’s mentor, quickly pushed Local H back into the studio to record their next album. Lucas took this as a positive: Island committing to their long-term development courtesy of a sophomore release. “I don’t think we realized how precarious our position was at the time,” he says. “We thought, Yeah, these guys are going to give us time to grow. But from things I later heard behind the scenes, everyone was pressuring [Bosso] to drop us.” As it turns out, Bosso’s goal was to record the next album and get it out before Island could drop the hammer.

By the time album No. 2, As Good As Dead, was set to be released in April 1996, Lucas was confronted with the reality of being on a major label. “That was the first time somebody [at Island] told me, ‘You’ve got to sell 100,000 copies or else you’re gone.’” Fortunately, radio and MTV were more than copacetic with the album’s second single, “Bound for the Floor,” and within a few months the band blew past the 100,000 mark. These unit-shifting metrics renewed Island’s faith in Local H. The label green-lit album No. 3, thereby retracting the sword of Damocles hanging above Lucas’s and Daniels’s heads.

Which brings us to the heretofore unnamed Pack Up the Cats, Local H’s watershed album that in several parallel universes is afforded the same “Best of the 1990s” reverence as Radiohead’s OK Computer, Spiritualized’s Ladies and Gentlemen We Are Floating in Space, Nirvana’s Nevermind, Pearl Jam’s Ten, and Neutral Milk Hotel’s In the Aeroplane Over the Sea. “I wanted to make a record that 13-year-old me would have fucking loved,” Lucas says. “And here, I finally had access to all the materials to do that. I had this idea in my head and knew exactly what I wanted to do; the label was onboard, and they were ready to take things to the next level.”

Lucas was listening to a truckload of classic rock at the time, and felt determined to bring in somebody with the experience to produce something with a timeless sound. “I knew we were going to make this concept record, which automatically sends you back to the ’70s,” he says. “And one day I heard Killer Queen on the radio and thought, We’ve gotta get this guy.”

The “this guy” in question was Roy Thomas Baker, the legendary producer who gave the world not just a ton of Queen albums, but seminal classics from the Cars, Journey, Devo, Yes, and Cheap Trick. Excited by Local H’s fully formed demos, Island brought Baker in, ramped up the recording budget, and left the band to do their thing. No interference, no second-guessing. At long last, Local H was exactly where they wanted to be. And they weren’t about to squander the opportunity.

It’s easy to assume concept albums were exclusively a prog-rock affair before Green Day’s American Idiot drop-kicked them into the alt-rock mainstream. The truth is, Local H beat Green Day to the punch by a good six years. Pack Up the Cats spins a heck of an album-long yarn, musically and lyrically chronicles the rise and fall of a rock band, from the blistering opening track “All-Right (Oh, Yeah)” to the melancholy-yet-hopeful closer “Lucky Time.” Songs creatively segue from one to another, with callbacks sprinkled in like finely ground Adderall. The lyrics alternate from earnest and hopeful to world-weary cynical and back again. And unlike much of Local H’s earlier, more aggressive work, melody, hooks, and earworm-riddled riffs are unabashedly front and center. Each track stands confidently on its own merits, from the “Day Tripper”–esque “She Hates My Job” to the seamlessly blended triple threat of “Hit the Skids,” “500,000 Scovilles,” and “What Can I Tell You?” And yet the 15 songs become all the more powerful in each others’ company. Pack Up the Cats’ only known kryptonite is your media player’s shuffle feature.

Island knew it had something special on its hands with Pack Up the Cats, and was primed to promote the living hell out of it, as well as its catchy leadoff single, “All the Kids Are Right.” “The wind was at our back and everybody at Island was marshaling the troops,” Lucas says.

And then the merger happened.

This was not akin to that time Polydor fused into Island Records — a.k.a. the “good for Local H” merger. In fact, this was anything but good news. In May of 1998, while the band was in studio finishing off Pack Up the Cats, Polygram — Island Records’ parent company — joined forces with Universal Music Group. Lucas describes the so-called friendly takeover as a “bloodbath.” In the weeks that followed, countless Island employees — including the band’s biggest supporter, A&R guru Bosso — were laid off. Others jumped ship. When the smoke cleared, Lucas and Daniels couldn’t track a familiar face at their own label. And just like that, Local H and their pending masterpiece went from high-priority to “Who are these guys?”

Universal’s priority in the wake of the merger was ensuring that U2 didn’t defect to another label. “All of their energy was focused on making sure the cash cow wasn’t going to go away,” Lucas recalls. “And I get that. Everybody’s got families and they’ve got to keep their jobs, and if U2 goes away, that’s it.”

As a result, the giant push Island pledged for Pack Up the Cats was watered down to a soft launch under Universal. The album hit stores on September 1, 1998, spent a mere two weeks on the charts, and, as noted in this article’s opening hypothetical, never climbed higher than 140. Moderate airplay and decent MTV rotation for “All the Kids Are Right” wasn’t enough, despite the single’s abject catchiness and a rather cutting-edge-looking music video by 1998 standards. Adding to the speculation that Universal was simply phoning it in: The label never got around to releasing a second single. With this, any lingering momentum was dialed down to zero.

Pack Up the Cats did manage to garner some critical praise by year’s end. Spin called it one of the best releases of 1998. And the Chicago Tribune upped the ante, declaring it the second-best album of the year. Unfortunately, the album was now beyond commercial resuscitation.

Although the Universal merger derailed Pack Up the Cats’ success, the changing musical climate may have played a role as well. Unlike the alt-rock heaviness that rang in the decade, things had skewed far more commercial by 1998, with artists like Semisonic, Harvey Danger, Ben Folds Five, Barenaked Ladies, and the Goo Goo Dolls finding their way onto alternative radio. Meanwhile, the harder-edged fare began leaning into a far more Limp Bizkit–y direction. Local H may have created their magnum opus, but it dropped at a time when nu metal and rap rock were staking their claim in the industry. “We tried to make a timeless record, but sometimes people want timely records — ones that are of the moment,” Lucas says. “It’s like, ‘All right, I’ll play that 20 years from now, but right now I wanna listen to this other thing.’”

In 1997, Local H was happily performing at festivals alongside Beck, Blur, and other artists they deeply respected. In 1998, the Pack Up the Cats’ touring schedule saw them sharing bills with rapping white guys in shorts. With anemic record sales leading to dwindling crowd sizes, the Local H sheen had worn off for Lucas and Daniels. The fun was gone. One of the album’s more memorable lyrics prophesied this very situation: “I’m in love with rock n’ roll, but that’ll change eventually.” A few months later, Daniels left the band, further mirroring the album’s “rise and fall of a rock and roll band” thematic arc.

Still signed with Universal, Lucas eventually chose to soldier on, recruiting former Triple Fast Action drummer Brian St. Clair to take over behind the kit. They set to work on a new collection of songs for what would be their fourth major-label release. But the label’s confidence in the band — if not basic awareness — was low. Universal made Local H play showcases for label executives, the kinds of live performances typically relegated to unproven newcomers. Lucas felt he was being asked to justify his existence. Further dismayed by the process, he took a fatalistic approach to pitching the new album to his label. He submitted the demos and invited Universal to drop them if they weren’t onboard. Universal wasn’t, and did exactly that.

Aside from the uncertainty that comes with closing out your major-label tenure, Lucas felt a sense of relief: “We were in a place where nobody knew what was going on, and we were able to get out of there on our own terms.” The band jumped over to the independent label, Palm Pictures, and released Pack Up the Cats’ follow-up, Here Comes the Zoo, in 2002. Since then, Local H have put out several studio albums on a slew of independent labels. Although Lucas describes Pack Up the Cats as the album that almost permanently broke his band, he remains fiercely proud of his creation, which has built sufficient cult status over the years to warrant a recent 20th anniversary U.S. tour. And despite feeling more comfortable with the move to boutique record labels, he doesn’t regret having signed with the majors. “I was never forced to make a record that I hated, or represent myself in any way other than how I wanted to be represented,” he explains. “So signing with Island was the right thing to do. And when we decided to leave when we did, that felt like the right thing to do as well.”