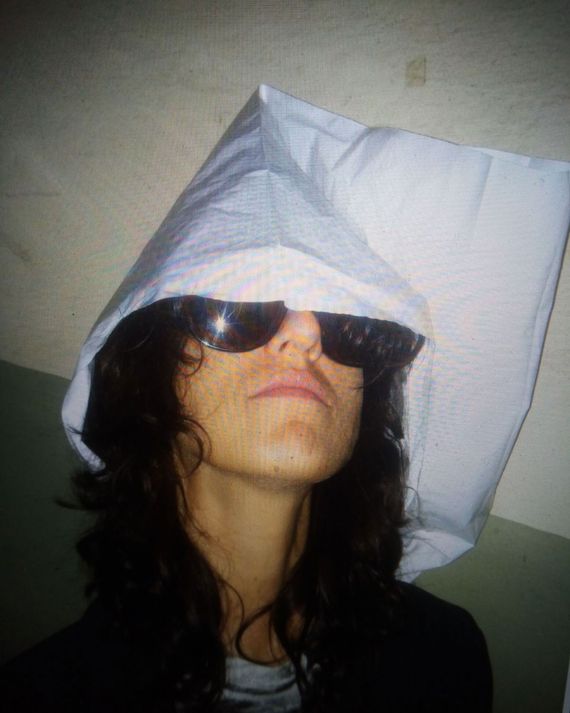

Banu Cennetoğlu was born in Ankara, Turkey, and lived in Paris, New York, and Amsterdam before settling in Istanbul, her home since 2005. She’s best known for the List, an ongoing project to widely disseminate a list of names of the tens of thousands of migrants and refugees who’ve died trying to make a new life in Europe since 1993. That project, to say the least, has struck a chord: it was repeatedly vandalized when it was exhibited in Liverpool. After representing Turkey in various global art extravaganzas, including the Venice Biennale, documenta, Gwangju Biennale, and Manifesta, Cennetoğlu prepares to return to the U.S., where she lived between 1996 and 2001, with a solo exhibition at the SculptureCenter in January. It centers on a 128-hour-long film she composed with painstaking diligence from the distaff digital record she’s made of her life in the years since she returned to Turkey.

In Cennetoğlu’s multidisciplinary practice , she mixes documentation of her personal life — photos and home videos — with ephemera recording its larger cultural context — newspaper and the TV news clips. She is 48, which means she can remember life before this smartphone era’s digital ubiquity, and has already lived through several rounds of technological obsolescence, all of which inform her work and her sense of memory. Like other artists of her generation, her work refracts other transitions too, the rise of political Islam, the end of the Cold War, and the stalled courtship between Turkey and the European Union.

Turkey is a land of competing identities, and competing senses of its own history. After the ’90s — an era described as a “lost decade” due to unstable politics, a lagging economy, and out of control urbanization, came Recep Tayyip Erdoğan with his socially conservative AK Parti (Justice and Development Party) which has ruled the country since 2002. What was at first sold to the world and his people as a globalist and economically liberal pro-European solution full of optimism has since evolved into autocracy. Turkey hasn’t left the global headlines since, starting with 2013’s blood-drenched Gezi Park protests against his administration, and the failed coup three years later. Erdoğan has firmed up his grip on power, despite concerns about how he runs the economy. The once rollicking press has been systematically tamed. Occasional shut-downs of Twitter or YouTube have since become the ordinary. Wikipedia is still inaccessible in the country to this day. Maybe not surprisingly in this context of oppression, Turkey is rarely the central subject in Cennetoğlu’s work but a faint specter haunting her treatment of trauma, either collective or personal.

Cennetoğlu’s 128-hour and 22-minute film has a title to match its running time: 1 January 1970 – 21 March 2018 · H O W B E I T · Guilty feet have got no rhythm · Keçiboynuzu · AS IS · MurMur · I measure every grief I meet · Taq u Raq · A piercing Comfort it affords · Stitch · Made in Fall · Yes. But. We had a golden heart. · One day soon I’m gonna tell the moon about the crying game. The tour-de-force documents the artist’s life these last 12 years, since the year after she moved back to Turkey, comprising sequences of images and occasional videos solely culled from electronic devices Cennetoğlu has owned since June 2006. Throughout the film, the artist and the many people she crossed paths with appear in formative, trivial, mundane, or humdrum moments. We see the Gezi protests and gatherings for Hrant Dink (Turkish-Armenian journalist and editor shot to death in 2007 by a nationalist in front of his newspaper) alongside Cennetoğlu visiting her mother in the hospital for her mother or cooking in her kitchen.

I spoke to Cennetoğlu from her Harbiye apartment. The conversation started in Turkish but switched to English while occasionally returning to our shared mother tongue.

Let’s start with the exhibition. How did the works come together?

The exhibition presents four existing works in a novel and site specific constellation. Curator Sohrab Mohebbi was interested in the film while I was working on it last winter for my Chisenhale Gallery exhibition in London. After the film’s premiere, he invited me to show it at the Sculpture Center. And after my site visit in August, we decided to show it together with three other pieces from the last eight years.

The second large work is the daily newspaper archives that I have been working on since 2010. I’ve collected daily national and local papers, printed a single day, and bound them on black hard covers with the content alphabetically ordered. The work conceptually, also formally, deals with politics and hierarchy of “news” dissemination while generating a portrait of different geographies in this particular point in time. Hence we are showing six compilations: Turkey, Switzerland, Arabic-speaking countries, Cyprus, U.K., and Germany. The work is about newspapers being a public space about collective memory. I am interested in the ways ads are juxtaposed next to news, how news is broken on a local and national outlet, or even the quality of the paper used for print. The Arab Spring had just happened while I was working on the Arabic version, and it was interesting to trace ways different Arab countries reported on it.

OffDuty stems from my documenta 14 project. Nine aluminum letters were borrowed from the Museum Fridericianum’s façade and six missing letters were cast in brass imitating the existing ones to read BEINGSAFEISCARY, which was a graffiti I had seen in Polytechnico in Athens. Once d14 was over, we returned the “originals” to Fridericianum and six new casts became OffDuty. I am interested in creating a new constellation with existing works — each work is like a word and each new configuration has a different capacity. Here is an unusual juxtaposition in terms of politics of memory since two works cover almost the same period and offers an entanglement of what is considered public and private. Also, my other pieces’ creation processes are in 1 January 1970 – 21 March 2018…

1 January 1970 – 21 March 2018 … is a very ambitious undertaking. Could you explain the idea behind the work?

The resource for the film’s content comes from all the electronic devices including hard disks, smartphones, digital cameras, as well as materials I downloaded, PDF attachments I received, and images I was hashtagged in. Digital devices use a unix time system, which marks undateable digital photos with January 1, 1970 or January 1, 1980, and this caused the first two-hours 15-minutes and 12-seconds of the film to follow a non-chronological order. In this section, the sequence jumps from my daughter’s fifth birthday party to her second, and then fast-forwards to the present due to inaccurate dates. The rest follows a chronological order based on dates the images entered my devices, starting from June 2006.

Dates are crucial for the film — you were also born in 1970, for example. Why did you choose June 2006 to start from?

The fact that I was born in 1970 is totally coincidental. I chose June 2006, because it is one year before I conceived my daughter and the first dissemination of the List in Amsterdam.

You don’t call the List an artwork, but rather a growing public database. How does the film respond to the List, which you’re widely known for in global arena?

On the public level, both works respond to my frustration of trying to keep the record of people losing their lives because of political instability. When I ask if I have the right to do something about this situation, I can at least have a historical archive and document the possibility of having a life and family outside turmoil. I want to look into the contrast between daily life and practice. I live in Istanbul, you live in New York, both in messed up situations.

I have been involved with the List on different levels for many years. The situation is worse than 2002 when the change of policies was already urgent. When we look at last decade, it is one of the worse one in the world history, not only in Turkey and Europe, we are in an undeclared ongoing World War III. Hard to put in concrete words, but the work departs from this contrast. I needed to look at what I have accumulated. I did not want to weed out, choosing one over the other for any reason. It is a circle with hundreds of tangents.

What are some of the stories behind the work’s long title?

Titles are an integral part of my work. I tried but it was impossible to reduce 12 years and 46,685 files to one line. As a big Clarice Lispector fan, I am totally inspired by The Hour of the Star, which had 13 subtitles, separated with ors. Mine are with ands. One of my favorites is keçiboynuzu (meaning carob in Turkish), for the particular effort it requires to eat. You have to constantly chew it just to get little flavor. My mother who used to love it; she always told me I was similar to keçiboynuzu — always investing so much effort to gain little in the end. In terms of Guilty feet have got no rhythm, I love Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou [George Michael]! Also, this was the title of my Kunsthalle Basel exhibition in 2011 and I wanted to recycle it.

You avoid a narrative or hierarchy between the images. How did you maintain the rawness of your reality without being too personal?

Well, it is personal but also it is collective. Obviously I am the common denominator, or carrier, but it is also collective and collected history. Because the majority was not shot to be shown, there is not one dominant narrative or construction. You see me with my mom at a hospital, marching at a Gezi Park protest, and then cooking at my kitchen. Putting the images together was a challenge, because I had to revisit moments with certain emotional charges and I had to bear the boredom of going through trivial images I barely remember. Bearing both on my and the audience’s end is the strongest part of this work.

Are there moments or people you hesitated to include?

There were moments I was skeptical about showing, but the work is a confrontation to myself. The only way to achieve this was to show everything despite their reasons, whether this is boredom, embarrassment, or anguish. Separations, reunions, funerals, hospitals, openings, demonstrations with many trials and errors are all in there.

How do you document divorce, for example?

My ex-husband starts to disappear from the photos and you see me with a new partner.

What kind of relationship do you expect the audience to build with such a personal and time-requiring work?

This is the periphery of the reality without a peak or climax, because during the climax, our cameras are usually off. The images I present give them the material to build their version of a story. With patience, they realize their story starts to grow. At that point, the images are not mine, but then the audience’s.