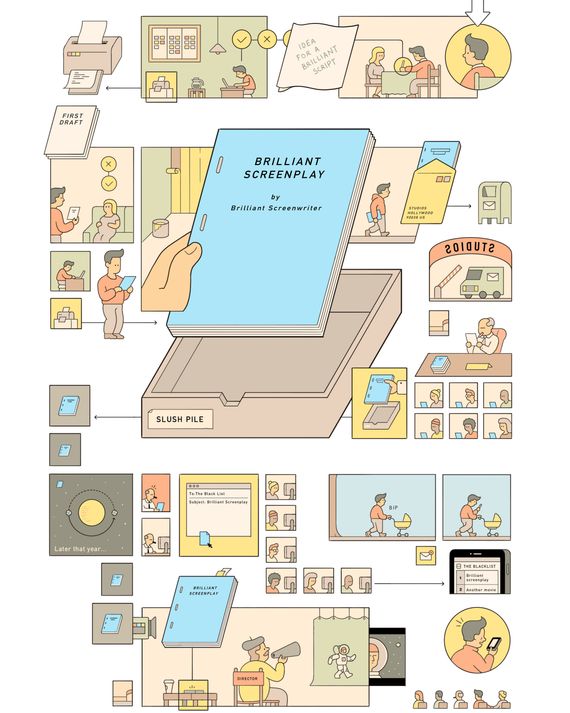

This week marks the release of the 14th edition of the Black List ÔÇö the annual rundown of the most-liked unproduced screenplays to make the rounds in Hollywood as voted on by 300 studio and production-company executives. Over the past decade, the list has become not only an index of hot properties but a kind of super-early Oscars preview ÔÇö these are the movies weÔÇÖll see getting trophies sometime between 2020 and 2030. ThatÔÇÖs not hype: Ten of the last 20 Best Screenplay Oscar winners first showed up on the Black List, which was founded and is overseen by Franklin Leonard, a development exec who has worked with, among others, Will Smith and Leonardo DiCaprio. American Hustle, Argo, Arrival, Hell or High Water, The Imitation Game, Juno, Manchester By the Sea, Michael Clayton, Spotlight, and Whiplash were all Black List scripts; so is this weekÔÇÖs new arrival Bird Box.

The roster of Black List screenplays that have gone on to be produced and distributed runs to 300 ÔÇö almost as impressive a number as the 700 that (so far) havenÔÇÖt. That would be a great batting average in baseball and is an astonishing one for film development, especially since a significant number of Black List scripts are not really meant to be produced. TheyÔÇÖre biopics of people who havenÔÇÖt sold their life rights, or based-on-a-true-story accounts that would never clear any studioÔÇÖs legal department but still serve as effective calling cards for their authors ÔÇö showy work that can put them on the map, demonstrate their skill at dialogue, character, and/or structure, and improve their chances to be hired for a project a film company wants to make.

But the Black List serves another purpose: ItÔÇÖs a yearly glimpse of the state of the art by the artÔÇÖs next great group of creators. Critics often speak approvingly of movies that feel ÔÇ£of the moment,ÔÇØ but because of the vagaries and challenges of production, that moment can be maddeningly long in coming. The Ruth Bader Ginsburg biopic On the Basis of Sex, which opens this week, was a Black List selection ÔÇö in 2014. How It Ends, an action film that arrived earlier this year, made the list way back in 2010. And the Best Picture nominees Nebraska and The Revenant took eight years to move from script to screen. Any yearÔÇÖs most-acclaimed movies usually started as glimmers in a writerÔÇÖs eye between two and ten years earlier. Those perfect Trump-era takes? They were probably written during the Obama era.

But the arrival of the Black List allows us to look at Hollywood in a different way: What are writers most eager to pursue right now? There are 73 class-of-2018 Black List scripts (it took at least seven votes to make the list, and this yearÔÇÖs winner, Elissa KarasikÔÇÖs Frat Boy Genius, received 36). Together, they constitute a kind of group show of writers at or near the beginning of their careers (the typical Black List scribe can be found somewhere on IMDB, often under ÔÇ£miscellaneous crewÔÇØ); their work collectively showcases unmistakable themes, frustrations, and obsessions that are indeed of this moment.

This yearÔÇÖs scripts include at least two with central roles for trans protagonists, and the roster of up-to-the-minute villains, according to the listÔÇÖs loglines, includes ÔÇ£Gamergate trollsÔÇØ and a ÔÇ£social-media influencer.ÔÇØ One theme, though, announces itself louder than any other (no, not that one). A good writer knows to avoid anything too on-the-nose, which is why there appear to be zero scripts about you know who. But one Trump-adjacent plotline ÔÇö how did [assholeÔÇÖs name here] ever get so much power? ÔÇö is pervasive. Frat Boy Genius is about Snapchat co-founder Evan Spiegel. Cody BrotterÔÇÖs Drudge, about Matt DrudgeÔÇÖs rise during the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal, also made this yearÔÇÖs top four, and other scripts on the list include takes on (if not takedowns of) Rupert MurdochÔÇÖs ex-wife Wendi Deng, former Gawker editor A.ÔÇàJ. Daulerio, and Chris Wylie and Cambridge Analytica. (Almost a decade later, The Social Network, a 2009 Black List selection, clearly casts a long shadow.) Biopics or episode-in-the-life-of stories are pervasive: Sally Ride, Bill Gates, Vanilla Ice, and a high-school-age Samuel L. Jackson all have scripts devoted to them, as do Richard Williams (Venus and SerenaÔÇÖs father), Tiger Woods, and Kobe Bryant (Mike SchneiderÔÇÖs Mamba focuses on the sexual-assault case against him).

Given its yearlong ubiquity in headlines, #MeToo is, perhaps, the most striking omission from the current list ÔÇö though an understandable one given the likelihood of almost any screenplay reaching the desk of at least one offender. Race, however, proved an irresistible subject. In Sascha PennÔÇÖs CI-34, a black agent teams with a Mafia hit man to solve the 1966 murder of a civil-rights activist in Mississippi. A 1964 murder involving white supremacists is the subject of Michele AtkinsÔÇÖs One Night in Mississippi; the title character of Nicholas MarianiÔÇÖs The Defender is a black defense lawyer in the Jim Crow South; and in Chris Kekaniokalani BrightÔÇÖs Conviction, Clarence Darrow finds himself defending the white murderers of a native Hawaiian who had been falsely accused of rape. Some scripts offer more contemporary perspectives: Meredith DawsonÔÇÖs Spark is about an African-American woman encountering Silicon Valley VC bro culture, and Queen & Slim (by Master of None Emmy winner Lena Waithe, one of the listÔÇÖs few recognizable names) depicts a black couple on a first date who go on the run after killing a cop in self-defense.

As ever, thereÔÇÖs a lot of sci-fi, with heavy emphasis on altered consciousness, timestream do-overs, and loss. Young writers have evidently been watching Groundhog Day as well as a lot of Black Mirror; they also seem to have spent a good deal of time staring at screens while thinking, ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm losing my mind,ÔÇØ which feels very fin-de-2018. The overall theme is one of intense melancholy. The logline for Mattson TomlinÔÇÖs Little Fish reads, in part, ÔÇ£a couple fights to hold their relationship together as a memory-loss virus spreads.ÔÇØ In Alanna BrownÔÇÖs The 29th Accident, a man loses his wife on their wedding day only to wake up next to her four years later. The consciousness of a dead man is implanted in a new body 20 years later in Matt Kic and Mike SorceÔÇÖs The Second Life of Ben Haskins. In Naked Is the Best Disguise (by The Imitation GameÔÇÖs Graham Moore, the only Oscar winner on this yearÔÇÖs list), ÔÇ£a woman who deals in black-market memories is accused of murdering a man she does not remember knowing.ÔÇØ Meet Cute, by Noga Pnueli, is a time-travel comedy about a woman trying to repeat and thus fix a first date. And In Retrospect, by Brett Treacy and Dan Woodward, portrays a man trying to dive into his estranged wifeÔÇÖs subconscious to retrieve her after ÔÇ£an experimental procedure.ÔÇØ

A couple of categories are Black List perennials: The killer high-concept sell will never go out of style. Who could resist the logline for Chris Thomas DevlinÔÇÖs Cobweb (ÔÇ£Peter has always been told the voice he hears at night is only in his head, but when he suspects his parents have been lying, he conspires to free the girl within the walls of his houseÔÇØ)? Sold! In this case, literally: Lionsgate is putting up the money. The Black List is not an unknown-talent contest; more than two-thirds of the films on the list already have producers attached, and more than a quarter have financing. But a great five-second pitch never hurts, and youÔÇÖd have to be profoundly incurious not to want to know at least a little more about Jason RostovskyÔÇÖs Hare (ÔÇ£What starts as a fun day for a group of friends in the woods turns into a living nightmare for one rabbitÔÇØ) or Jason KesslerÔÇÖs Escher, in which the artist uses ÔÇ£his unique view of the worldÔÇØ to battle Nazis as part of the Dutch Resistance during World War II. Even screenplays the descriptions for which are so low concept they could seemingly appear on any yearÔÇÖs list ÔÇö like Greg KalleresÔÇÖs Our Condolences, about a couple reevaluating their relationship after their friends lose a child, or Covers, by Flora Greeson, about a woman trying to become a music producer ÔÇö are intriguing precisely because itÔÇÖs clear that their power must be in the execution, not the concept.

Not all of these scripts will become movies, and not all that do will be any good; Dan FogelmanÔÇÖs Life Itself, which finished second among all scripts on the 2016 Black List, became one of 2018ÔÇÖs most critically reviled movies. And inevitably, since Hollywood never met a list it didnÔÇÖt try to game, some titles may have been boosted by the clubbiness or horse-trading (ÔÇ£IÔÇÖll vote for your guy if you vote for mineÔÇØ) to which any enterprise like this is susceptible. Still, itÔÇÖs hard not to feel that if this list resulted in 73 immediate green lights, the next two years at the movies ÔÇö including the misfires ÔÇö would be infinitely more interesting. ÔÇö Mark Harris

Since weÔÇÖre impatient and couldnÔÇÖt wait for HollywoodÔÇÖs green light, we asked comic artists to draw pivotal scenes from five of the screenplays on this yearÔÇÖs Black List, including Elissa KarasikÔÇÖs┬áFrat Boy Genius┬á(which received 36 votes); Harry TarreÔÇÖs┬áQueen┬á(8); Michael WaldronÔÇÖs┬áThe Worst Guy of All Time, and the Girl Who Came to Kill Him┬á(26); Amanda IdokoÔÇÖs┬áDead Dads Club┬á(11); and Jason KesslerÔÇÖs┬áEscher┬á(8).

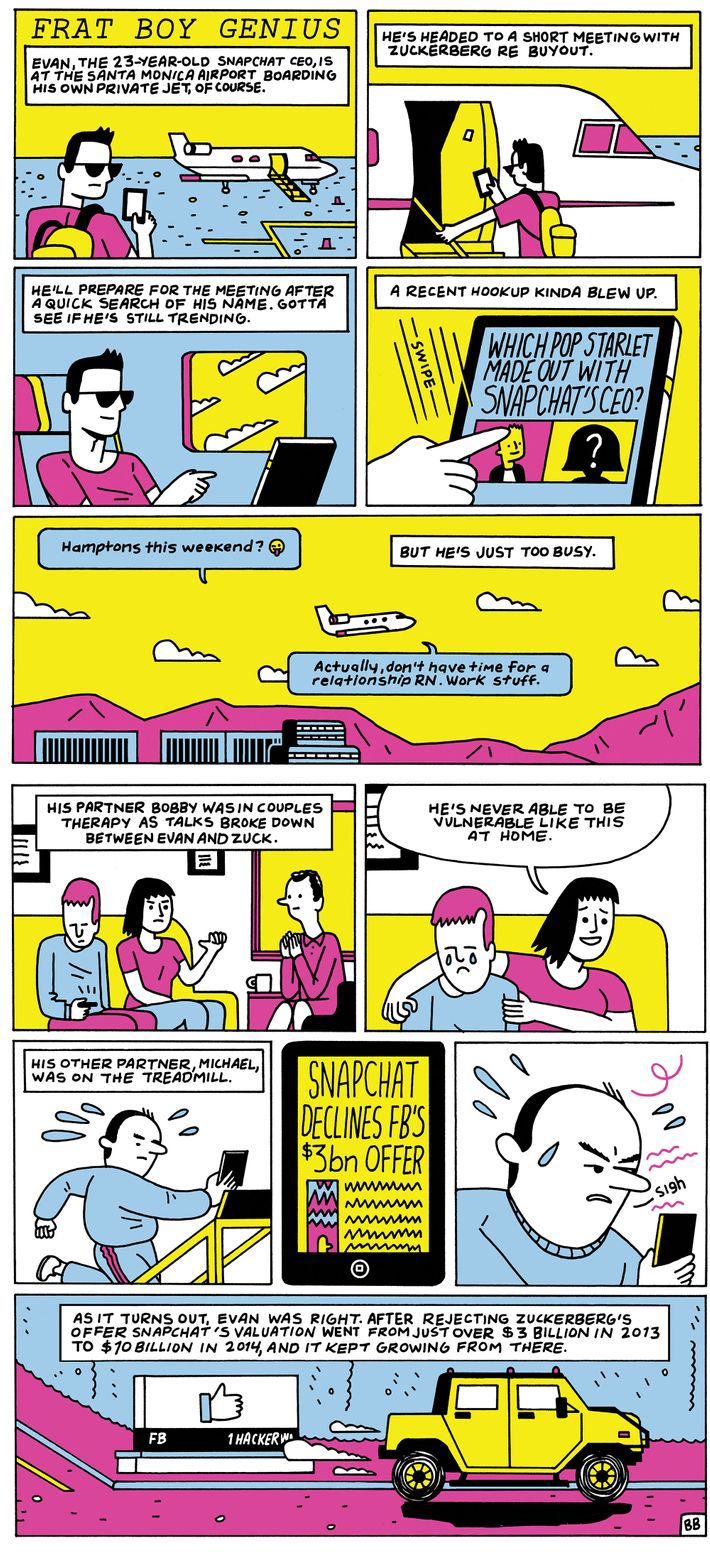

Frat Boy Genius

Screenwriter: Elissa Karasik

Illustration: Box Brown

Logline*: A disgruntled Snapchat employee narrates the rise of her former Stanford classmate and current boss Evan Spiegel.

The Plot: In this docudrama, Spiegel, a listless, hard-partying Stanford student, has the bright idea to create a photo-messaging app in which all pics disappear a few seconds after the recipient views them. Working closely with his best friends, he gets the product, first called Picaboo, off the ground. Nobody seems interested, though, until he markets it to teenagers and changes its name to Snapchat. In this fictionalized scene, Karasik imagines that Facebook calls, and Spiegel jets off to a meeting with Mark Zuckerberg ÔÇö but leaves his partners in the dark.

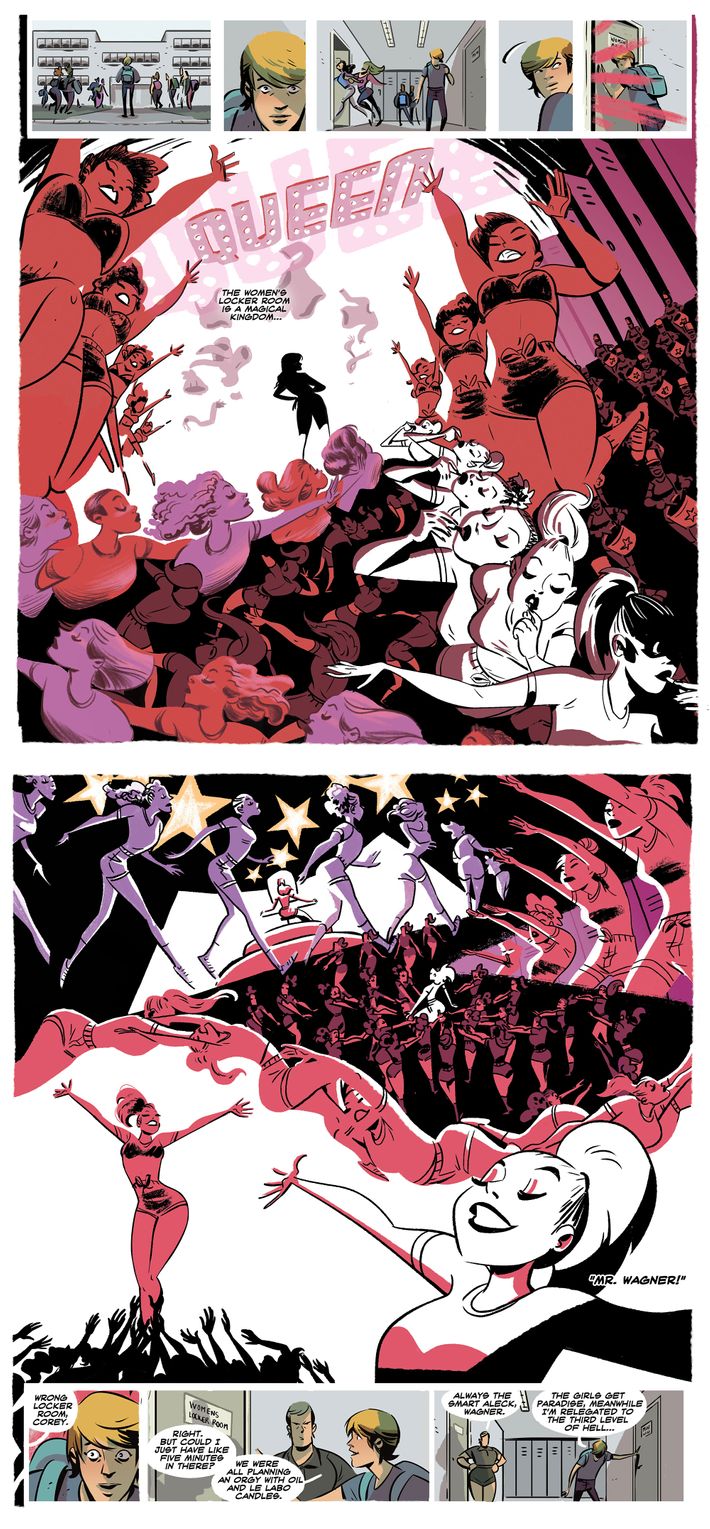

Queen

Screenwriter: Harry Tarre

Illustration: Elsa Charretier

Logline: Based on the inspirational true story of the worldÔÇÖs first openly transgender high-school prom queen, Corey Rae.

The Plot: Corey Wagner is a transgender girl living in suburban New Jersey, but she hasnÔÇÖt come out yet. Even though she has a mostly supportive family, Corey has to wrestle with her identity and with rumors that sheÔÇÖs gay, as well as the ordinary challenges high-schoolers have to deal with. Among her many goals is one day to be able to use the womenÔÇÖs locker room ÔÇö a place that, in her daydreams, she imagines to be ÔÇ£a magical kingdomÔÇØ of Busby BerkeleyÔÇôstyle dance routines. As Corey eventually starts to open up about who she is, the school is thrown into disarray and she discovers who her real friends are.

The Worst Guy of All Time, and the Girl Who Came to Kill Him

Screenwriter: Michael Waldron

Illustration: Jorge Corona

Logline: Barret is a social-media influencer, the worst guy ever, and the eventual president of the United States. Dixie is a badass freedom fighter, sent back from 2076 to kill him before he takes over the world and ruins the future. They fucking hate each other. Then they accidentally fall in love.

The Plot: Lights up on a postapocalyptic hellscape in what was once Atlanta. As the film opens, a group of badass, menacing soldiers, who work for a tyrannical warlord called the Duke, are set upon and killed by a freedom fighter in a velociraptor helmet ÔÇö our wisecracking, 20-something heroine, Dixie. She has been tasked with traveling back to 2018 to kill the DukeÔÇÖs younger self, a ÔÇ£millennial shitheadÔÇØ and ÔÇ£social-media influencerÔÇØ named Barret. One of BarretÔÇÖs followers, Miller, also races back to stop her, and the trio get wrapped up in all manner of chrono-illogical high jinks.

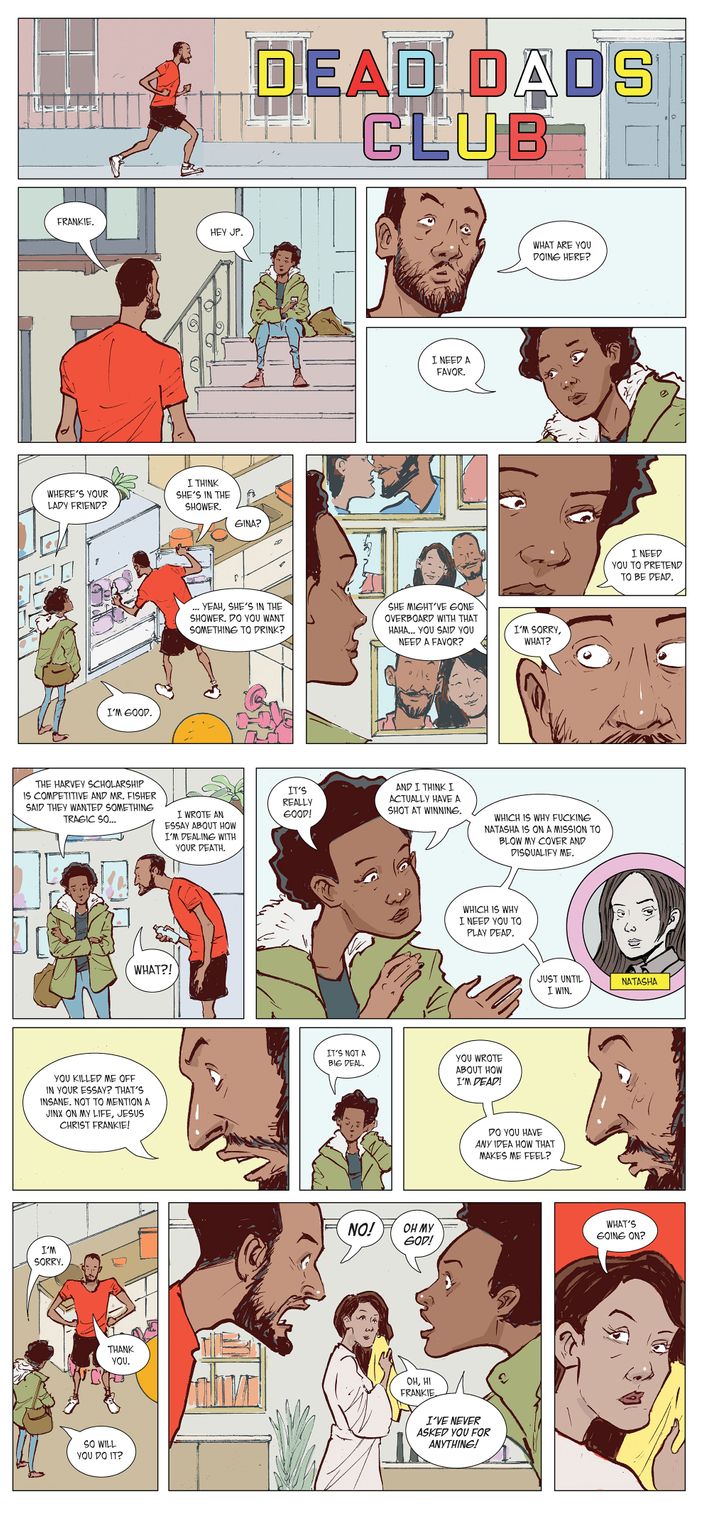

Dead Dads Club

Screenwriter: Amanda Idoko

Illustration: Sonny Liew

Logline: In an effort to find a more interesting story for her college-scholarship application, a high-schooler lies about her fathers recent death. But when the father tries to take advantage of the lie by faking his own death, the high-schoolers nemesis investigates, and bodies start piling up 

The Plot: After struggling to find an appropriately tragic angle for her scholarship-contest essay, 17-year-old Frankie Wilson makes up a story about coping with her fatherÔÇÖs death. The trouble is, her father, J.P., is not dead. Having recently separated from FrankieÔÇÖs mom, he is living with his girlfriend, Gina, dreaming about starting a fitness empire. But FrankieÔÇÖs hypercompetitive, Harvard-bound classmate Natasha is already onto her ruse, so Frankie realizes that she needs things to be a little more convincing. Which means asking her father if heÔÇÖll pretend to be dead. Needless to say, heÔÇÖs shocked. With an assist from Gina, Frankie finally persuades her dad to fake his own death.

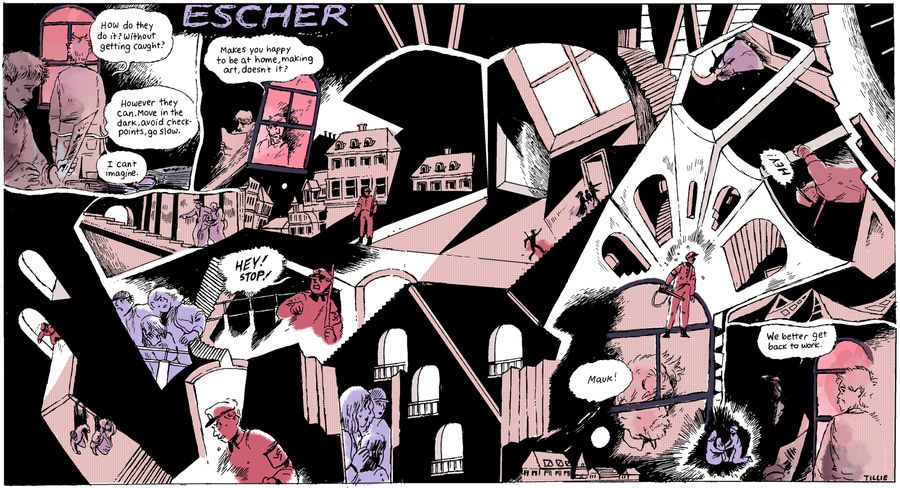

Escher

Screenwriter: Jason Kessler

Illustration: Tillie Walden

Logline: Famed artist M.ÔÇàC. Escher reluctantly uses his unique view of the world to help the Dutch Resistance fight Nazi occupation during WWII. Inspired by the life and art of M.C. Escher.

The Plot: The story follows 46-year-old M.ÔÇàC. Escher in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands in 1944. In his efforts to save a 9-year-old Jewish girl named Rebecca from a Nazi work camp, Escher becomes involved with the Resistance, making elaborate maps for the good guys. In this scene, Escher ÔÇö referred to by his nickname, Mauk ÔÇö is in the middle of making map prints when he falls into a surreal daydream about a Resistance fighter helping a mother and daughter escape a Nazi soldier using the wending and impossible stairways that made the artist famous.

*Loglines courtesy of the screenwriters.

*This article appears in the December 24, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!