“After December 14, we will live in a world where everyone knows Peter Porker,” says comics writer Dan Slott. “Laymen on the street. Kids with their lunch boxes and onesies. Everyone is gonna know who Spider-Ham is.” He pauses. He laughs at the ridiculousness of it all. “What a world.”

No, those aren’t typos. Slott is not talking about Peter Parker, the Spectacular Spider-Man. He’s talking about Peter Porker, the Spectacular Spider-Ham. The former is one of the best-known characters ever to appear in fiction, a man granted amazing powers after being bitten by a radioactive spider. The latter is a relentlessly bizarre offshoot, a spider who gains his own abilities after being bitten by a radioactive pig. For decades, he slung webs in obscurity as a Z-list Marvel Comics character. That’s all about to change. This Friday, Spider-Ham makes his improbable big-screen debut in the critically acclaimed animated feature Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, in which various alternate-dimension versions of Spidey team up to fight for justice. Porker is easily the strangest of the group, and the story of his rise to prominence is just as strange.

Unsurprisingly, Spider-Ham began as a joke. The year was 1983 and the comics industry was in a state of upheaval. After five decades of relying on sales at newsstands and drug stores, publishers had recently started using an innovative method of pushing their wares: the so-called direct market. Its ins and outs aren’t worth belaboring, so suffice it to say that the new approach was based on selling in specialty stores primarily designed to sell comics and comics-adjacent products. It was anyone’s guess where the direct market would go next, and a particularly nerve-racking rumor had just started to spread, one involving the venerable publishing house Marvel Comics, home of Spider-Man.

“Around that period of time, for some reason, the direct-market retailers, who are a superstitious and cowardly lot, were convinced that Marvel was gonna start opening up a chain of comic-book stores to compete with them,” recalls Tom DeFalco, who was, at the time, one of Marvel’s most prized writers and editors. He theorizes that people were thinking about the Disney stores at Disneyland and Disneyworld and figuring Marvel would create something like that for the comics market. But there was a problem with that rumor. “Marvel, at that time, was not in [those] leagues,” DeFalco says with a laugh. “We were a big company in terms of the comic-book market, but a very small company in terms of the company market.”

This topic came up during a routine bullshitting session between DeFalco and fellow Marvel writer and editor Larry Hama. “Larry and I were just laughing about this whole concept of Marvel opening up its own chain of stores,” DeFalco says. “We were like, ‘Haven’t these guys walked into a Disney or a Warner Bros. store? What those stores sell are apparel and plush toys. There were some Marvel T-shirts in those days, and that’s all we had in terms of apparel. And Larry and I were saying, ‘There’s no way we’re gonna have a plush toy. Plush is where the real money is, in terms of licensing, but we don’t have the capability for plush.’” Hama entertained a hypothetical, remembers DeFalco: “Larry said, ‘The only way we can do plush is if we had funny animal versions of our characters.”

One never knows where inspiration will strike, and in that moment, it shot directly into the Marvel offices. Quoth DeFalco: “And I said, ‘Like what? Peter Porker, Spider-Ham?’”

The pair laughed at the sheer ridiculousness of the notion, and Hama wanted to one-up his friend. “Larry came up with some other goofball name and I came up with a goofball name — it’s always dangerous to have me and Larry in an office together,” DeFalco says. Soon, they were anthropomorphizing Marvel icons like Captain America and Ghost Rider, too. “I’m saying, ‘Captain Americat!’ and he’s going, ‘Goose Rider!’ Just back and forth with this stupid stuff.” Jokes always carry with them the risk of coming true, and a chance encounter brought this one out of the realm of fantasy. “Somebody comes in and listens to our nonsense for a few minutes and says, ‘What is this? Is this a book you guys are gonna do?’” DeFalco recalls. “Larry or I go, ‘Yeah, we’re coming up with a funny animal book featuring — what was it? — Peter Porker, Spider-Ham! Yeah!’ The guy’s going, ‘That sounds ridiculous.’ But Larry and I, the more we laughed about it, the more we were like, ‘This is really not a bad idea.’”

There was a long tradition of so-called “funny animal” comics stretching back to the 19th century and wending through masterpieces like Carl Barks’s take on Donald Duck and George Herriman’s iconic “Krazy Kat” strips. That said, the genre had largely gone extinct long before the ’80s, meaning a Peter Porker book might be a hard sell. On the other hand, Marvel was in an experimental mode in those days: Eternal rival DC had found success with the Superman films, whereas Marvel had been so cavalier with its licensing arrangements that it was powerless to get its own adaptations off the ground. “There was all this talk at Marvel at the time about, ‘Maybe we should create new stuff that isn’t already mortgaged,’” recalls Hama, who had a great deal of experience with humor comics, having been editor of Marvel’s Mad magazine knockoff Crazy. “There was a renaissance of new stuff all of a sudden. It was easy to do a two-issue or four-issue mini-series. That was your trial balloon.” Emboldened, the pair went to speak with Marvel editor-in-chief Jim Shooter.

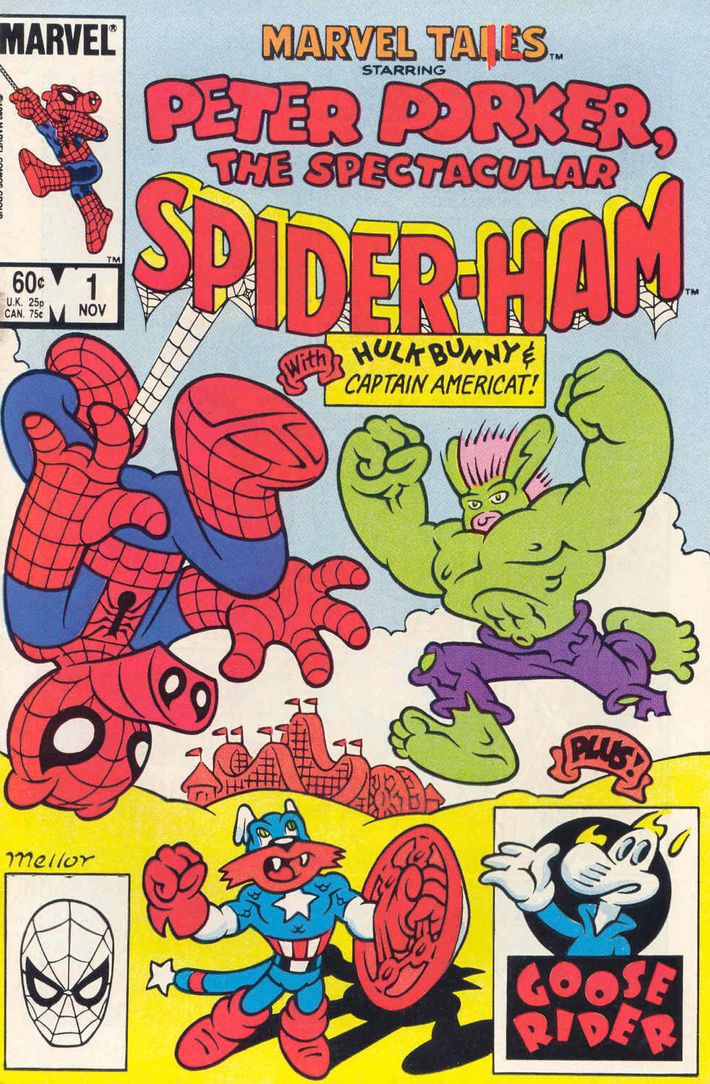

“We walked into Jim Shooter’s office and said, ‘We wanna come out with a one-shot comic book,’” DeFalco says. “We proposed [Spider-Ham] to Shooter, who was used to us coming to him with all sorts of nonsense. Jim, true to form, was like, ‘If I say yes, will you get out of my office?’ We said, ‘Yeah!’ He signed off on it and we started work on the comic book.” The plan was to have DeFalco write the one-shot and for a talented but virtually unknown artist named Mark Armstrong to draw it. They hashed out what they wanted the character to look like and even had a friend of Hama’s who made dolls to produce a prototype plush toy of it. As for the comic, it was called Marvel Tails — a play on the long-running reprint series Marvel Tales — and it was adorable.

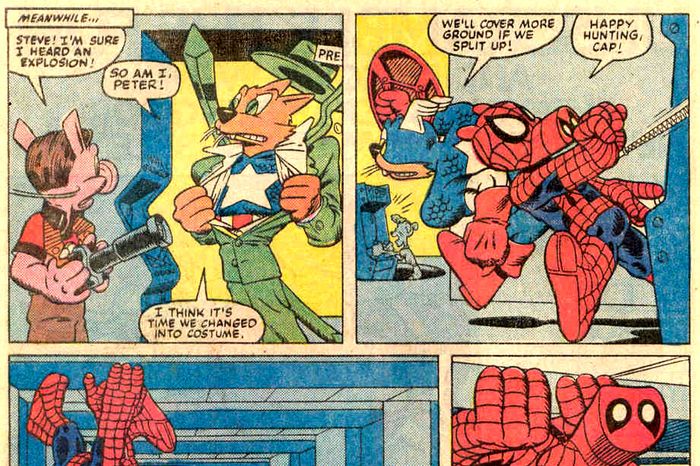

“Yawn! I need some action!” So begins the first line of dialogue in the comic, placed in a thought bubble above the head of a pig-headed, midget-bodied figure in a Spider-Man costume. This is Peter Porker, a character whose backstory is never once explained throughout the entire issue. All we learn about him is that he works as a photographer for The Daily Beagle (run by J. Jonah Jackal, of course) and is pals with Steve Mouser, a.k.a. Captain Americat. There’s a weird narrative involving a scheme to destroy a video arcade, and the adventure is just gag after gag. A game designer named Dr. Bruce Bunny gets transformed into Hulk Bunny (not exactly a pun, but we’ll let it slide), chaos ensues, Banner is returned to his original state, the arcade plot unravels, and the story thing ends on an incongruously pathos-filled note: “But what of Bruce Bunny?” the narration reads. “Is he destined to live the rest of his life under the monstrous shadow of the Hulk-Bunny? Will he — can he — ever again know peace? Only time will tell.” Luckily, there was a five-page backup story about Goose Rider to leaven the whole experience out.

Marvel Tails No. 1 hit stores in September 1983. Initially, DeFalco and Hama regarded it as a failure for one key reason: It didn’t nab them their coveted stuffed-animal contract. “We grabbed the plush doll, went to licensing, and said, ‘We have this great idea you can license!’” says DeFalco. “And they looked at it and went, ‘We can’t even get Spider-Man dolls! How the hell are we gonna get Peter Porker dolls?’ So we thought, We had fun doing the comic book, at least. We went on with our lives.”

This is where the story gets complicated. DeFalco has a dramatic version of what happened next. “A few months later, I get a call to come to Shooter’s office,” he recalls. “He looks up at me and says, ‘Galton wants to see you.’” Jim Galton was, at the time, the president of the company and a notoriously bottom-line-oriented cutthroat. “I said, ‘About what?’ And Shooter said, ‘It’s your mess, go up and fix it. Now go up to Mr. Galton’s office.’” In DeFalco’s recollection, he did as he was told and found Galton and Jim Walsh, the man in charge of Marvel’s distributor. “Jim [Galton]’s got these sales reports in front of him and he says, ‘Jim has a question to ask you.’ I’m thinking, Our distributor has a question to ask me? He says, ‘You ever hear of a title called Marvel Tails?’ I say, ‘Yeah, it’s reprints.’ And he says, ‘No, no, I’m talking about Tails — T-A-I-L-S.’ And suddenly, my heart stops. I’m thinking, What the hell did we do?”

As DeFalco tells it, the situation grew even more tense and confusing. “I said, ‘Oh, yeah, um, that was a comic that featured a character called Peter Porker, Spider-Ham,’” he says. “Galton just stares at me. I go, ‘It was a one-shot.’ Galton said, ‘And you had something to do with this?’ I said, ‘Uhhh, yessir.’ I’m thinking, Whatever it is, I’ll take the heat. I’m just assuming we’ll be yelled at. But Jim Walsh says — I don’t remember the exact number, but it was something like, ‘It sold 65 percent on the newsstand.’” Don’t worry about the exact meaning of that statistic — just know that it was very good. “Galton turns to me and goes, ‘When’s the next issue coming out?’ I said, ‘It was a one-shot.’ Walsh repeats, ‘It sold 65 percent on the newsstand.’ Galton says, ‘When’s the next issue coming out?’ I say, ‘It was a one-shot.’ Galton says, ‘You’re not listening to me, Tom. When’s the next issue coming out?’” DeFalco laughs in the retelling. “I said, ‘Oh! In about three months, sir!’ Walsh stands up, shakes my hand, and says, ‘It’s a pleasure doing business with ya, son.’” He rushed downstairs, told Hama, and they set out in a panic to produce a monthly Peter Porker series.

The only trouble with that story is that Shooter says it’s complete bullshit. “Galton never had any meetings with DeFalco,” Shooter tells me. “That’s total baloney.” In Shooter’s retelling, Galton wanted to transition Marvel out of comics and into children’s books, and felt that kids’ comics might be a good next step in that direction. Thus came the advent of Star Comics, a new line of comics targeted at children, which was launched in 1984. Shooter’s version of the story is that he himself commissioned a Peter Porker series because the one-shot had sold well and he needed content for Star. Galton, he says, couldn’t have cared less about the specifics. As he puts it, “Galton wouldn’t know a comic if it bit him on the throat.”

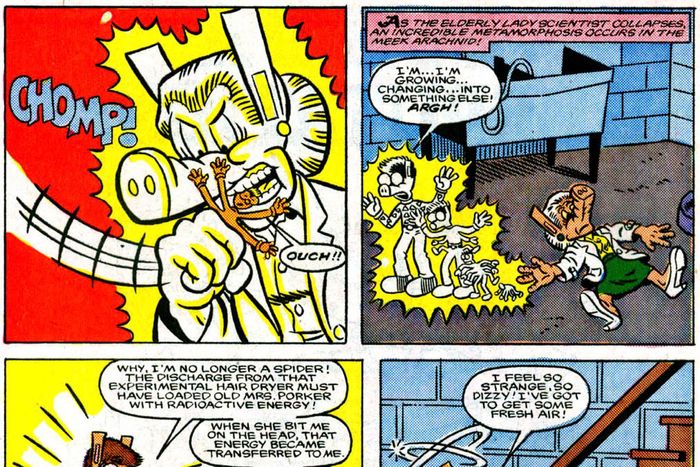

Whatever its origins may have been, Peter Porker, The Spectacular Spider-Ham No. 1 arrived in March of 1985. Armstrong returned, but DeFalco and Hama passed writing duties on to a scribe named Steve Skeates. The resulting series was somehow even weirder than the original one-shot. The stories saw Doctor Doom reimagined as Ducktor Doom, Doctor Strange as Croctor Strange, Sub-Mariner as Sub-Marsupial, and — best of all — Ant-Man as Ant-Ant. Only in issue 15, written by Steve Mellor, did we learn Porker’s origin story: a super-genius pig named May Porker created “the world’s first atomic powered hair dryer,” irradiated herself, and, for reasons not explained, bit a spider that was on her wall. The spider morphed into the shape of an anthropomorphized pig who retained its spider abilities (wall-crawling, etc.) and was taken in by May, whose radiation experience warped her brain into thinking this new creature was her nephew. Got all that?

Alas, quirky absurdity can only get you so far in this world. Sales declined, and after 17 issues, the series was canceled. Hama blames a changing entertainment landscape. “The market and the end user were mutating,” he says. “In the late ’70s and early ’80s, I used to go to comics signings and there would be 10- and 11-year-old kids lined up around the block.” Then came the mass popularization of video games. “The kids were less likely to use their quarters for comics. They were more likely to drop them into slots,” Hama says. The remaining comics readers tended to be older and more self-serious. “So that was the problem: Peter Porker had a stigma as a kiddie book.” It seemed that Spider-Ham had had his run and was bound for eternal consignment to the discount pile.

But the porcine powerhouse left a mark on one particularly influential reader: Slott. As a child, he was a Spidey obsessive and he adored Peter Porker. “I read those when they were first coming out and I was like, This is insane,” the writer recalls. “This is gonna sound silly, but my favorite thing was that the nostrils in his snout were the Spider-Man eyes. That’s just insane.” Flash-forward to the late aughts, when Slott was firmly ensconced as the lead Spider-Man writer at Marvel. He got a side gig writing for an Activision video game called Spider-Man: Shattered Dimensions, in which the player plays as a handful of different Spider-Men from different alternate universes. The opportunity opened up by that conceit led Slott to propose a gag. There’s a scene early on where the player sees a web of different Earths, displayed by the mystical Madame Web, and he got the creators to identify one of them onscreen as the home of Spider-Ham. It was a brief nod, but Slott was emboldened and requested something unreasonable.

“I wanted to do a post-credits gag,” he recalls. “I wanted you to be back in Madame Web’s lair and Spider-Ham pops out and goes, ‘What’d I miss?’ And they were like, ‘You want us to build a new model for a new character that’ll only appear after the credits?’ And I was like, ‘It’ll be funny!’ And they were like, ‘No!’” He was undeterred. “It was the one thing where I stuck to my guns,” he says. “I was like, ‘You hired me because I know Spider-Man and I know the fans, and I’m saying this’ll make the fans happy.’ They eventually gave in to me.” The game came out in 2010 and, sure enough, if a player stuck around, they’d see young Peter Porker make a seconds-long cameo. Before its release, Slott was vindicated. “We did a panel at WonderCon to show how it was going, and they showed the opening cinematic with the Spider-Ham reference,” he says. “And afterward, all these fans came up and were like, ‘Is Spider-Ham in the game? Will we see him?’ They’re hugging me and the video-game guys are like, ‘Okay, okay, you do know these people.’”

And yet, it still wasn’t enough for Slott, and his creative insatiability led in no small part to the film in which Porker is making his debut. While working on Shattered Dimensions, Slott realized he wanted to take the core idea of alternate Spider-People crossing over with one another and put it on steroids. “I called [Spider-Man editor] Steve Wacker from the video-game company in Quebec, and I went, ‘We should do this as a comic, but we should bring in every Spider-Man ever,” he says. “We should do what they can’t do.” Wacker was receptive but the then-EIC of Marvel, Axel Alonso, had them hold off on it for a few years. Finally, he got the green light and dubbed the subsequent 2014 comics story “Spider-Verse.” He swears up and down that that term, now the core of the title of the new film, is his creation, and his alone. “‘Spider-Verse’: That’s me, and every time it’s said, I get a nickel,” he jokes. “For me, the cool thing is seeing the word Spider-Verse everywhere and the idea of throwing all these Spider-Men together, and I’m like, ‘I’ll take it!’”

“Spider-Verse” put Spider-Ham back in the spotlight as one of the dozens and dozens of Spider-Folks who come together to fight a multiversal threat. So beloved was his portrayal within the walls of Marvel that he was brought back to be the co-star of a monthly series, Spider-Verse, in 2015, a subsequent monthly called Web Warriors, and a currently ongoing crossover event called “Spider-Geddon.”

But more notably, he appears prominently in the new movie, where he’s voiced with pitch-perfect aplomb by comedian John Mulaney. Spider-Ham has been part of the movie since its initial treatment by Phil Lord and Christopher Miller, and the directors have fought to keep him. “Every time we were struggling with something, the pig was the first thing to put a target on,” says co-director Peter Ramsey. “You sit down at a conference table after a screening and that’s where the conversation goes first: ‘Do we cut the talking pig? Is that a bridge too far? Is that four bridges too far?’” However, they stuck to their guns and the pig stayed in the picture. He now graces posters and trailers across the planet.

In short, Peter Porker’s future is brighter than it’s ever been. When I mention to DeFalco and Hama that Spider-Ham will be on the big screen, both of them confess that they hadn’t been informed of that development and had no idea it was happening. (Ah, the superhero industry. Always putting characters’ creators first and foremost.) Nevertheless, they both seem amused that this offhand idea they concocted as a stupid joke 35 years ago has somehow managed to dig its hooves into the ground and hold on for dear life. Hama credits Porker’s unlikely success to his sheer idiosyncrasy. “If you’re doing a formula, nobody cares,” he muses. “It comes down to that: No matter how wacky or crazy it is, if people can sense the sincerity and the fun in it, they’ll go for it.”