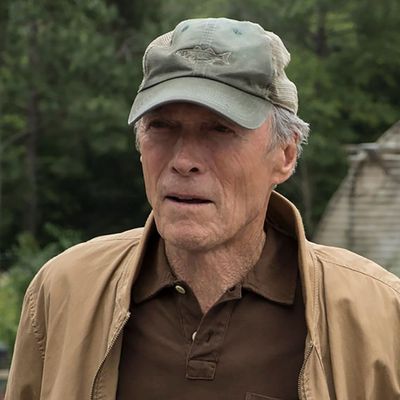

Slipped into theaters with few advance screenings or the usual ballyhoo for a Clint Eastwood film (this one featuring what might be the 88-year-old’s last leading performance), The Mule turns out to be a modest but reasonably suspenseful and abidingly eerie portrait of the aged white American male trying vainly to forestall rejection and irrelevance. The solution that this particular aged white male stumbles on is going to work for a murderous Mexican drug cartel, which gives him, wouldn’t you know, the money to make America great again. His America, anyway.

Eastwood plays 90-year-old Earl Stone, a passionate, lifelong horticulturalist, and if you can get past the image of Eastwood circa Dirty Harry (1971) squatting over flowers rather than bullet-ridden corpses, you’ll begin to feel the resonances. In the tidy screenplay by Nick Schenk (Gran Torino), a horticulturalist is defined as someone who nurtures things that bloom and live for a day — as opposed to Earl’s ex-wife, Mary (Dianne Wiest), and estranged daughter, Iris (Alison Eastwood), whom he effectively abandoned for demanding too much day after day after day.

A charmer, a horndog, a wiseacre, Earl took advantage of the privileges that society once gave him, but that society is gone with his youth. The dang internet has killed his nursery business. The bank has foreclosed on his house — and will soon take back the VFW center in which he and his fellow vets (Earl served in Korea) drink and dance the polka with the tootsies and reminisce about the days when people like him were respected. The only people who can bail him out — give him the money to save his house and help his granddaughter, Ginny (Taissa Farmiga), get through school — are snarling, tattoo-covered narcos who cross back and forth over the border, making America a hell on Earth. Earl takes the money, of course. He loves being flush, respected, at the wheel. He doesn’t know that the DEA (led by Colin Bates, played by Bradley Cooper) has an informer in the mix and is on the tail of the vaunted drug mule called “Tata.” That means “grandpa” in Spanish, but Bates doesn’t know to look for a skinny old white guy.

The Mule was inspired by Sam Dolnick’s New York Times Magazine article, “The Sinaloa Cartel’s 90-Year-Old Drug Mule,” and you should know that despite the commercials, it never crosses the line into action-movie mayhem. That might disappoint some people, and Eastwood means it to. For nearly half a century, his alter-egos did not take emasculation lightly: He’d rasp some variation of, “You don’t listen, do ya’ asshole?” and pull back his fist or pull out his big gun. But the nonagenarian Earl Stone isn’t Harry Callahan or Bill Munny or even the once-militant Walt Kowalski of Gran Torino. Early on, before he understands how easily they could kill him, Earl sasses his Mexican handlers. He says, “Ya vol, mein herr,” with a silly German accent. But when they start to rough him up and hiss cabron in his face, he does nothing, nada. He’s not a fighter. He only wants to sniff flowers. Clint Eastwood has aged into Ferdinand the Bull.

Which is fascinating. Although the crudeness of Eastwood’s political thinking was on display at the 2012 Republican convention, he’s a canny caretaker of his own myth, and he’s much more evolved than the last comparable Republican action hero, John Wayne — who in the soggy, self-conscious Western The Shootist (directed by Eastwood’s old mentor, Don Siegal) succumbed to the “Big C” but made sure to take a lot of scummy thugs with him. The Mule isn’t meant to lionize this old American icon, but to acknowledge his limitations and note — with sadness — his passing from the scene, along with all the other neglected veterans and failing small business owners.

The thing is, Earl wants to evolve, even if that evolution is opportunistic. He strives to be there for his ex — when she gets sick. He risks his Mexican handlers’ wrath by pulling off the road with his pick-up full of cocaine to help a black couple change a tire; and while the woman’s face freezes in anger when he says he likes “helpin’ the Negro folks out,” Eastwood wants to be clear that Earl is not a racist, just a wee bit out of touch. (Although Earl must really have had his head in the loam.) You don’t always know where Eastwood’s sympathies lie. Is he making fun of a guy pulled off the road by DEA agents who cries, “Don’t shoot me!” and reels off statistics about his chances of being killed at that moment, or is he acknowledging the spike in shootings of innocent motorists? Whichever, it’s a bracing scene.

As usual, Eastwood’s direction is lean, brisk, and pointedly unfussy. The casting is spot-on. Andy Garcia has a nice turn as a relatively civilized kingpin who develops a tender affection toward his nonagenarian mule. The pensive Ignacio Serricchio has a few good moments as a cartel enforcer who wants to shoot Earl and then, in spite of himself, begins to like the gringo. Cooper and Richard Pena as another DEA agent get some tricky, funny rhythms going when they bully a potential informer into helping them, and Cooper has a wonderful scene with Eastwood in a diner when he half-listens to the old man — whom he doesn’t know to be the infamous “Tata” — hold forth on the importance of being there for one’s family.

However graceful, The Mule would be a small potatoes without the lift it gets from Eastwood’s mythic persona. He has few expressions, but the ones he has are riveting, and age has been unusually kind to his features. Although he’s stooped now and thin-shouldered, he’s every inch Sergio Leone’s Man With No Name. It’s just that at 88, the Man With No Name wants something to put on his tombstone and for his family to cry when he’s gone.