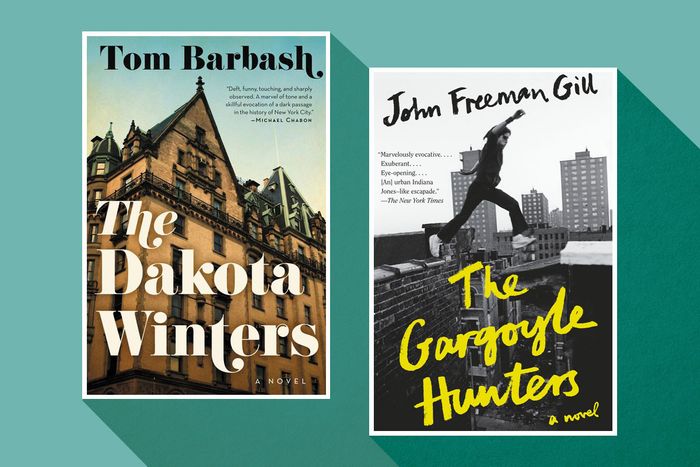

Tom Barbash’s novel The Dakota Winters (out this week from Ecco) and John Freeman Gill’s The Gargoyle Hunters (published last year, now out in paperback from Vintage) almost seem to run on parallel tracks. Both writers grew up on the Upper West Side in the 1970s, and both their books are full of atmospheric details about that particular grimy time and place. Both are also narrated by young men with problematic dads. Vulture asked Gill to speak with Barbash, and they wound up interviewing each other — about the always-creepy Dakota, vanishing New York places, and the incredible true stories (a building façade stolen and sold for scrap; John Lennon’s Bermuda Triangle sailing adventure) that wound up in their fiction.

John Freeman Gill: Anton Winter, the 23-year-old protagonist of The Dakota Winters, lives in the Dakota — the building that, in my favorite New York City novel, Jack Finney’s Time and Again, serves as a portal to 1882 New York. For me, your evocative descriptions of life in the Dakota served as a portal to 1979 New York, when I lived on the Upper West Side. So I’m wondering, what did the Dakota signify for you when you were growing up in the neighborhood?

Tom Barbash: It was like a huge, slightly frightening, and gorgeous castle. And it was soot-covered back then. I guess they’ve cleaned it up. But back then, it was —

J.F.G.: It was gloomy.

T.B.: Yeah. Looming over the neighborhood. And you heard about all the famous people who lived there, and saw some of them in the neighborhood. But the building always seemed a little haunted to me. And then came Rosemary’s Baby, where you saw an actual corpse on the sidewalk, and where there were Satanists living within. That seemed to confirm it.

J.F.G.: I lived on 81st and Riverside, and you did have the sense that the Dakota was this castle on a hill where all the special people lived. The uncle of one of my friends was Carroll O’Connor.

T.B.: Archie Bunker!

J.F.G.: Archie Bunker lived in the Dakota. At what point did you decide that this was going to be where you would set your novel?

T.B.: Well, I became interested in the idea of John Lennon living there in that final year of his life, and wanted to write from the perspective of someone who knew him less as a celebrity and more as a neighbor — and also what it would be like to live in this kind of small town, where people who were famous, who got hassled in other areas, could sort of feel at ease.

J.F.G.: I love how you describe it as being like a European village.

T.B.: And your book is so much about what makes New York beautiful and individual: The architectural life of New York is so vividly described. So I’m wondering what kind of interest you had in the gargoyles of the Dakota?

J.F.G.: I never got interested in architecture until I was an adult, but my interest in the constantly evolving streetscape of New York came early because my mother was a painter who would go around painting streetscapes just as buildings that she loved were being destroyed. She started doing this in 1954. So when I was growing up, lost New York was still alive on the walls of my home. The 57th Street Automat was still serving cheesecake from our kitchen, and the Third Avenue El was still clattering down the front hall. I only became interested in the buildings per se after that. I think we took it all for granted, where we lived.

T.B.: I certainly did.

J.F.G.: It really doesn’t exist anymore. Near the end of the book, you say, “Where did the old people go? The crazy people, the drunks and the prostitutes, the chess-playing socialists go? The Upper West Side of our growing up had the whole world within, not just the pretty parts.” Are there aspects of New York that you felt died along with John Lennon in 1980?

T.B.: I do. It was almost right then that things changed. Columbus Avenue, which was my thoroughfare, really changed in the eighties, and it became this beacon for tourists and people from other parts of the city. It transitioned first to these kind of trendy cafés, and later to clothing stores. And then it was unrecognizable.

J.F.G.: I had a job at one of the first trendy spots on Columbus Avenue. I was a busboy at Lucy’s Retired Surfers Bar & Restaurant on 84th and Columbus. I’d come home at one o’clock in the morning and walk through this rather frightening dead zone.

T.B.: I remember that place.

J.F.G.: People lined up down the block to get in. It was probably very much how people experienced the Odeon in that Bright Lights, Big City era.

T.B.: There’s a section in your book that’s also something I tell people: “Go back and look at the 1970s movies like Dog Day Afternoon, or Death Wish, or The Taking of Pelham One Two Three.” You see how grimy the city was.

J.F.G.: Right, because the stories may be fiction, but it was the real New York City they were shooting in.

T.B.: And — as you know — you got accustomed to it, and you had your strategies for getting home at night.

J.F.G.: We both have “mug money” in our books — the few bucks you would stick in your pocket to give to muggers so they wouldn’t beat the crap out of you.

T.B.: And I’ll ask you, John, about the real-life heist that was an inspiration for you. Can you talk a little bit about how you took this incident that was intriguing and made it a centerpiece of your book?

J.F.G.: The incident you’re mentioning is this astounding, really larger-than-life architectural heist that took place in 1974. That year, an entire cast-iron façade of a landmark 1849 building was literally stolen over a period of weeks by thieves and sold to a scrapyard in the Bronx for a couple hundred bucks. The theft was a huge scandal — it made the front page of the New York Times after the head of the landmarks commission ran into the City Hall press room, all aflutter, and cried, “Someone has stolen one of my buildings!” And that’s a true story. To this day, no one actually knows who stole the final pieces, and I wanted to solve that mystery, so I put 13-year-old Griffin and his historic-preservationist father with somewhat lax morals at the heart of that heist. And for you, Tom, what event or events did you uncover in your research that made you say, “My God, I’ve got to weave this into my story”?

T.B.: I got very excited about John Lennon‚Äôs mission to learn how to sail in the spring of 1980. He bought a sailboat that spring and learned how to sail, and then he chartered a boat, a 43-foot Hinckley sloop, and was going to sail to Bermuda from Newport, Rhode Island. But the boat went through a storm over the Bermuda Triangle, and everybody got sick on the boat except for John because of his macrobiotic diet, which spared him. And at some point the captain, a man named Hank Halstead, was just too exhausted. He‚Äôd been sailing for 30 hours, and he went below and turned the ship over to novice sailor John Lennon. And John sailed for, the story goes, around seven hours through gale winds and high seas, singing. He claimed later that he channeled his Viking ancestors, and he sang filthy Liverpool shanties at the top of his lungs. He saved everybody‚Äôs life, and¬Ýat the end of it, he genuinely felt immortal.

J.F.G.: That’s a remarkable story.

T.B.: This was a man who’d had a creative drought for around five years, and when he arrived in Bermuda, he wrote most of the songs in “Double Fantasy” in the next couple weeks. He just had a tremendous breakthrough. So, in the same way that you brought father and son onto this mission to steal those artifacts, I contrived to have Anton, my narrator, take part in this trip.

J.F.G.: And Anton is having some struggles with his relationship with his own father, Buddy the talk-show host. But meanwhile, this episode in which John Lennon navigates through a deadly storm must have been awfully cathartic for John because his own father was a deadbeat merchant seaman back in England, wasn’t he?

T.B.: Yes. John‚Äôs father had left him when he was 2, and was away for most of the next three or four years. And when he returned, he kidnapped John and took him to Blackpool for three weeks. Eventually,¬ÝJohn had to choose between his mother and father, and ended up going back home with his mother. I think he had a great longing for his father, and there were lots of thoughts of what his father might be doing out on the sea, and I think it formed a big part of his desire to take this kind of a voyage.

J.F.G.: He went in search of his father and instead found himself.