I think we may have come to a fork in the road where conspiracies are concerned. For many years, conspiracy fiction and conspiracy theories traveled happily together, interacting and keeping each other in check. I grew up in the golden age of conspiracy fiction, which roughly went from, say, Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow in 1973 to Don DeLillo’s Underworld in 1997. During this nearly 25-year period, there was balance and even a sort of harmony. Naturally, the theories came first, and the fiction, in its inimitable, maximalist way, followed, creating space, providing cover, elucidating, explaining. But it no longer works like that. In the age of Donald Trump things have gotten seriously out of kilter. The conspiracy theory as a form has been weaponized, and it is now very hard not to question its function, and its usefulness, in fiction.

For me, this poses something of a dilemma, since all six of my published novels could reasonably be described as conspiracy thrillers. My latest one, Receptor (out next week from Picador), looks back at the CIA’s MK-Ultra program of the 1950s and tracks its influence up to the present day. I blend fact and fiction to create a sort of alternative history, but as a storyteller, what interests me most is finding a core of truth, an essence that pulses beneath the surface of events. So it should hardly be necessary to point out that while the conspiracies in my novels are not real, this doesn’t mean that I’m a liar. And yet, in a time when the word narrative comes with pre-fitted political bump stocks, maybe it is necessary to point this out. Because unlike in the 1970s, when paranoia was often the only sane response to what was going on, paranoia today seems to be more of a political blood sport than anything else.

There have always been conspiracy theories, of course, and the paranoid mind-set in America is not new. Jesse Walker’s 2013 book The United States of Paranoia and Kurt Andersen’s more recent Fantasyland both brilliantly chronicle the perennial American tendency to believe the unbelievable. They also make it clear that what Richard Hofstadter called the “paranoid style in American politics” is not limited to the fringes, but is, in fact, and always has been, about as mainstream as you can get.

When Hofstadter coined his famous phrase (in a lecture delivered just days before JFK was assassinated), his point was that “they” weren’t out to get you at all, that you really were being paranoid. But within ten years this paradigm had pretty much been turned on its head. Now, it seemed, they really were out to get you — whether you knew it or not, and generally you didn’t until it was too late. So what happened? And why did the works of fiction that reflected this paradigm shift resonate so deeply with people — both at the time and ever since?

Hofstadter wrote that American politics was often “an arena for angry minds” and that “much leverage can be got out of the animosities and passions of a small minority.” If that sounds familiar, it’s because the paranoid style has always been both a mind-set and a playbook, something innate, unruly, driven by demons, and at the same time something pliant, actionable, and never without a target or a scapegoat: the Illuminati, international bankers, Catholics, Communists, liberals, immigrants, the Deep State.

But maybe a case can be made that the 1970s were a little different. Is it really so surprising that the collective trauma sustained during Vietnam and Watergate should lead to a national mood of such unrelieved suspicion, disillusionment, and dread? It has often been said that the assassination of JFK marked a loss of innocence for America, or that at the very least it started a slow-burn process that continued with further assassinations, lies and atrocities abroad, and, eventually, the resignation of Richard Nixon.

James Ellroy disagrees. He introduces his great 1995 novel American Tabloid with this bold statement: “America was never innocent. We popped our cherry on the boat over and looked back with no regrets.” He’s right, of course. But he was also right when, in a later interview, he described the period between 1963 and 1968 as “the last gasp of pre-public accountability America.” Ellroy calls his Underworld USA trilogy a “sewer crawl through the private nightmare of public policy,” but not everyone lived in the sewers, and while Ellroy does a good job of taking the pre- out of prelapsarian, the reality is that for most Americans in the late 1960s and early 1970s, finding out that their presidents had lied to them was so profoundly shocking that it did constitute a sort of fall from innocence.

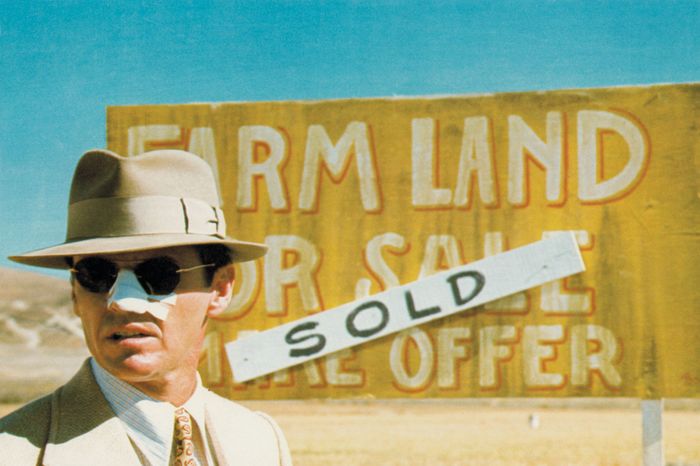

Naturally enough there was some explaining to do, and a good deal of this came in the form of conspiracy thrillers, the best of which included Alan J. Pakula’s Klute (1971), The Parallax View (1974) and All the President’s Men (1976), as well as Polanski’s Chinatown (1974), Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), Pollack’s Three Days of the Condor (1975), and Schlesinger’s Marathon Man (1976). In their different ways, these movies charted the gradual disempowerment of the individual in modern society and basically confirmed our worst fears: that we don’t really know what’s going on and we don’t really know who’s running things.

When J.J. Gittes was handcuffed to a car at the end of Chinatown, rendering him powerless to affect the outcome of events, a strange psychological shift occurred in American cinema, which mirrored the one going on outside. Because here was a familiar character — a private detective, effectively an avatar for rugged American individualism — who no longer had a reliable moral compass and could casually be crushed by malign, unknown forces.

So these conspiracies were a form of public accounting — and it seemed that the paranoia was justified, because with the Watergate, Church and Pike Committee hearings of the mid 70s, the curtain was finally pulled back and the fairly nefarious inner workings of the U.S. government were revealed. The novels and movies of this period were fiction, and mostly popular entertainment, but they packed a considerable punch — and not by stoking unrest or leveraging animosity, but rather by floating the modest idea that corruption and greed can sometimes be exposed to the light.

The conspiracy-theory aesthetic in fiction had a pretty decent half-life, but by the late 1990s it had more or less run out of steam. For one thing, people no longer found it shocking that those in power might be bad actors or that institutions, in the service of their own preservation, might routinely and reflexively work against the interests of individuals. And for another, conspiracy theory itself had become a devalued currency. Thanks mainly to the internet, the paranoid style was now back in force. Information overload led to a sort of heat death of what we know and understand, a point of entropy at which, if a conspiracy theorist believed one theory — chemtrails, say — they would most likely believe all of them: the moon landings, fluoridation, Waco, Lady Diana, the New World Order, WT7, take your pick.

It was then only a short step to the situation we find ourselves in today, where conspiracy theories are customized to achieve desired political outcomes and then injected into the news stream via social media. (This itself may sound like a conspiracy theory, but only if you’ve forgotten what an inveterate and transparent fabricator today’s theorist-in-chief is). No, with swiftboating, birtherism, voter fraud, anti-vaxxing, Pizzagate, crisis actors, false flags, and alternative facts, the conspiracy theory has clearly been weaponized in the most cynical and partisan way.

So where does this leave conspiracy fiction? Well, sort of in the lurch. But that’s okay, because really, we’ve moved on. It’s not that people don’t conspire anymore. We take it for granted that they do. The new challenge is to catch them at it — to identify the truth of any given situation, to back it up with evidence, and to inoculate that evidence against the twin viruses of perception management and narrative bias. A tall order. But that’s just what lots of investigative reporters are now doing, many of them inspired to become journalists in the first place by the work of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. A seminal text of the paranoid style was John Stormer’s self-published best seller None Dare Call It Treason (1964). This was followed some years later by Gary Allen and Larry Abraham’s even bigger hit None Dare Call It Conspiracy (1971). Perhaps now it’s time to round off the trilogy with None Dare Call It Truth.

On the fiction side, it’s a bit less clear what the exact labels or subgenres should be, or even if these are necessary anymore. Is Tony Gilroy’s movie Michael Clayton (2007) a conspiracy thriller? Is Peter Temple’s novel Truth (2008)? In both, the focus is less on the fact of corporate corruption being uncovered than on the toxic moral fallout it generates for those caught up in it. And more recently we’ve had Amazon’s Homecoming, an exquisite paean to ’70s paranoia but with a very up-to-date and genre-curious twist. Fiction is good at speculating, and interrogating, and perhaps the current vogue for dystopian fiction — Emily St John Mandel’s superb Station Eleven (2014), for example — is where that energy has come to rest. In my own work, paranoid dread is an ever-present dynamic, but the source of it is constantly shifting: from the smoking gun to the Cigarette Smoking Man, from the will to power to the power of artificial intelligence. It’s a valuable resource, and not one that will be running out anytime soon.