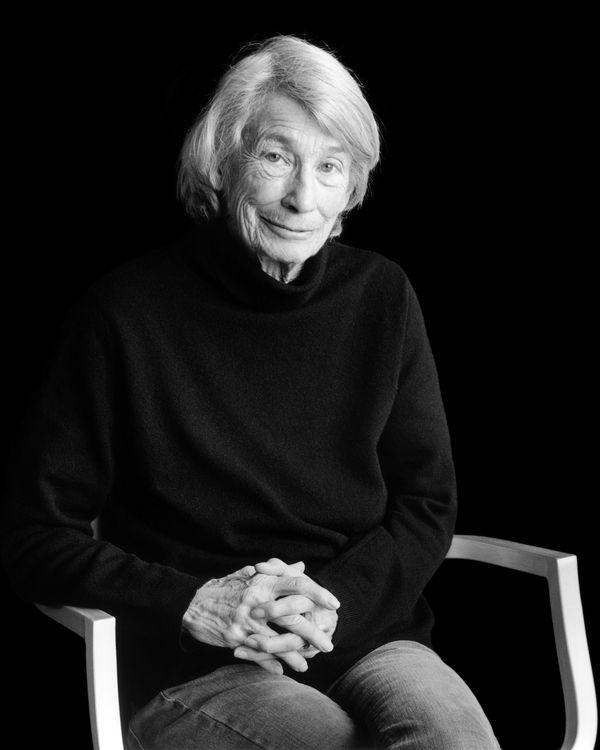

The acclaimed and wildly popular poet Mary Oliver died yesterday. Lindsay Whalen, whose authorized biography of Oliver is forthcoming from Penguin Press, remembers her subject, and the importance to Oliver of meeting fellow writers and poets ÔÇ£on the page.ÔÇØ

Mary Oliver wrote the poet James Wright for the first time in 1963.

She was 28 years old and unknown, and she had never met Wright. But she had taken his two collections with her when she left Ohio for the U.K. the previous year, and they saw her through a lonely, difficult period.

In London, Mary lived in a series of guest rooms and boarding houses during one of the cityÔÇÖs coldest winters, the same year Sylvia Plath ended her life. Her first book, No Voyage and Other Poems, had been accepted by J.M. Dent & Sons, and was published in September to little notice.

Her future was uncertain when she picked up her special-ordered copy of WrightÔÇÖs most recent collection, The Branch Will Not Break, from Foyles bookstore in November. She read the poems immediately and wrote to Wright that evening: ÔÇ£Tonight, in a room the size of a cupboard, I am broke, I am getting a cold, intermittently I am thinking of someone who never comes anymore, and nothing really matters. I am radiant with happiness because James Wright exists.ÔÇØ

So much of what I know of Mary Oliver is reflected in that simple page to Wright ÔÇö the willingness to be direct, the understanding of despair, and the insistence on joy. So, too, the instinct to look for a friend between the pages of a book. ÔÇ£I never met any of my friends, of course, in a usual way ÔÇö they were strangers, and lived only in their writings,ÔÇØ she wrote, in an essay about her insufficient childhood and its consolations. ÔÇ£Whitman was the brother I did not have.ÔÇØ

I had been reading Mary OliverÔÇÖs books closely for years when I wrote her a letter in the spring of 2016. I was not in the habit of writing to authors I admired, but I had a reason: I believed that the time to tell her story was now, and I was the one to do so.

To my surprise, she agreed to meet, and I flew to Florida to visit her some weeks later.

As arranged, I called from the airport, but when Mary came to the phone she sounded surprised to hear from me. It would no longer be possible for us to see each other. The reason had nothing to do with me, she said, but that was difficult to believe.

I spent the next four days in Florida, hoping my luck would change. I called as often as I had the courage, and made sandwiches from peanut-butter packets left out in the hotelÔÇÖs breakfast buffet. During the day, I distracted myself with driving, walking, and reading, over and over again, the same ubiquitous signage about the areaÔÇÖs nesting sea turtles.

Back home in New York I prepared to move on, and I almost had, when Mary asked to see my writing. I sent her the biography proposal I had taken over a year to research and write, and I waited.

Mary knew something about waiting. It took James Wright almost two years to respond to her first letter. By then Mary had returned from London, and settled in Provincetown. Finding an American publisher for No Voyage was a struggle, but the book was released by Houghton Mifflin in 1965.

ÔÇ£I have loved your poems for a long time, but until I found and read your book I hadnÔÇÖt realized how much they had come to mean to me,ÔÇØ James Wright wrote Mary that summer. ÔÇ£It is an extraordinarily beautiful book that youÔÇÖve written, and it haunts me in some secretly desolated place in myself where I had not hoped to see anything green come alive again.ÔÇØ

The week after I sent her my proposal, Mary left me a voice-mail inviting me to return to Florida in the coming weeks. ÔÇ£What I was interested in is your writing,ÔÇØ she said. ÔÇ£And youÔÇÖre wonderful.ÔÇØ Our interviews began soon after, but by then I knew we had already met in the way that mattered most: on the page.

MaryÔÇÖs correspondence with James Wright would continue until his death, in 1980. They would never meet in life, but Mary would dedicate her collection American Primitive to him, in memory. It won the 1984 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.

There is a beauty, and a purity, to that kind of connection, but I wouldnÔÇÖt trade it for the chance to know Mary Oliver as I have, in person and in earthly time.

On one of my last visits to Florida, in December, we sat in her bedroom talking, and I noticed that there was a page in her typewriter. By then illness had made life in the body difficult, and when I moved closer to the desk I saw that the page was hammered with letters, not all of them decipherable. In the center were the words on the page that I believe are her message to all of us: ÔÇ£Keep trying.ÔÇØ