The world of young-adult fiction is no stranger to controversy, whether itÔÇÖs a weeks-long war against a problematic book or a whisper network accusing a badly behaved male author. But even against this backdrop of continually percolating dramas, the saga surrounding Am├®lie Wen ZhaoÔÇÖs Blood Heir was unusually dramatic: a scattering of small, apparently disconnected fires started by persons unknown, all abruptly extinguished by the author herself yesterday when she called for her own book to be canceled.

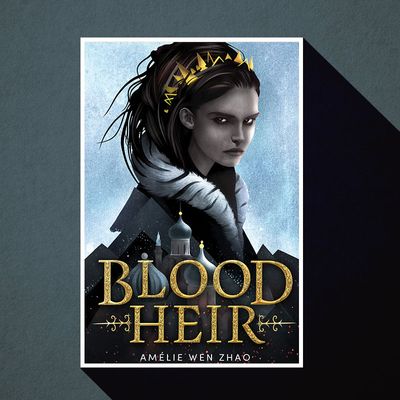

Blood Heir, the first in a planned three-book series, began as the ultimate social mediaÔÇômeetsÔÇôpublishing success story. Zhao matched with her agent, Park LiteraryÔÇÖs Peter Knapp, during a Twitter pitching event for marginalized creators (Zhao immigrated from China to the U.S. at the age of 18). Her fantasy series, a loose retelling of Anastasia with a diverse cast of characters and a hefty dose of blood magic, sold at auction in a high six-figure deal with Delacorte. And over the course of the past year, Zhao emerged as an active and outspoken participant in the YA community ÔÇö not just the author of a buzzworthy debut but an enthusiastic, effective communicator who was deeply engaged with issues of diversity and knew how to make herself heard.

ÔÇ£Set out with good intentions,ÔÇØ Zhao wrote in March 2018, in a post advising other writers on how to navigate social media. ÔÇ£Be enthusiastic, be positive, be supportive, cheer people on ÔÇö all those things youÔÇÖd want to find in a real-life friend, be those things online and in the writing community, too.ÔÇØ

A scroll through her Twitter history shows that Zhao generally followed her own advice in the year after she sold her book, boosting fellow authors and writing about the issues she faced as part of YAÔÇÖs nonwhite minority. (In one tweet, she mused: ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve been asked several times why I didnÔÇÖt write a Chinese #ownvoices novel. I donÔÇÖt want to be boxed into the permanent ÔÇÿOther;ÔÇÖ I want diverse books written by PoC to become part of the mainstream.ÔÇØ)

Early last week, however, influencers within the YA community began tweeting vaguely about an unnamed person engaged in bad authorial behavior: targeting book bloggers for harassment over negative reviews, ÔÇ£shit talking other authors of color.ÔÇØ The villainÔÇÖs identity was initially a mystery and source of fascination, but elsewhere, a woman who tweets under the handle @LegallyPaige wasnÔÇÖt being so cagey about naming names: ÔÇ£IÔÇÖll tell you which 2019 debut author, according to the whisper network, has been gathering screenshots of people who donÔÇÖt/didnÔÇÖt like her book and giving off Kathleen Hale vibes: Amelie Wen Zhao.ÔÇØ

Although LegallyPaige declined to offer proof of ZhaoÔÇÖs alleged screenshotting-with-intent, her thread now looks a bit like the opening salvo in a larger campaign to sabotage the debut author. A flurry of additional accusations followed: that Zhao had plagiarized a death scene from The Hunger Games, lifted a line from Tolkien, gotten the conventions wrong on her Russian-inspired charactersÔÇÖ names, and indulged in problematic world-building by putting a slave auction scene in her book ÔÇö in which a black character was ignominiously killed off.

Whether Zhao was guilty of any of the above is still up for debate, particularly in the absence of a finished book. (Blood Heir was not slated to publish until June; some reviewers had advance copies.) But unless we want to eliminate the Death Song trope from fiction or ding TolkienÔÇÖs own use of paraphrased Bible passages, the plagiarism allegations are shaky at best ÔÇö and the charge of racism, led by a series of caustic tweets from YA fantasy author L.L. McKinney, relies on both a subjective interpretation of the word ÔÇ£bronzeÔÇØ and an exclusively American reading of scenes involving slavery. Nevertheless, the latter allegations caught the attention of social-justice-minded readers, and the controversy began to balloon. A smattering of one-star reviews cropped up on ZhaoÔÇÖs Goodreads page. Book bloggers began announcing that they no longer intended to read Blood Heir. In a tweet thread that did not name or tag Zhao but was clearly about her, well-known author Ellen Oh wrote, ÔÇ£Dear POC writers, You are not immune to charges of racism just because you are POC.ÔÇØ

ItÔÇÖs worth noting here that the role of Asian women within YAÔÇÖs writers of color contingent has been a flashpoint for conflict before ÔÇö one that led Zhao to butt heads with YA queen bee Justina Ireland in May 2018. After Ireland wrote a (since deleted) tweet that some readers interpreted as exclusionary gatekeeping of the ÔÇ£POCÔÇØ label, Zhao launched a long thread asserting that Asian women are, indeed, women of color, including some pointed language about those who would suggest otherwise.

ÔÇ£You can delete your tweets, and weÔÇÖre not going to come into your mentions, but ask yourselves why you wrote those/agreed with those in the first place, and why there is such an outcry. While weÔÇÖre on the valid issue of anti-POC within POC groups, examine your own beliefs, too.ÔÇØ (She did not tag Ireland, but needless to say, everyone knew whom she was talking about.)

ItÔÇÖs impossible to say whether this eight-month-old beef helped spark a retaliatory campaign by IrelandÔÇÖs supporters, or perhaps primed critics to focus on ZhaoÔÇÖs alleged insensitivity to the history of African-American slavery. What is clear is that the current controversy speaks to a larger, ongoing debate in YA about marginalized identities, ÔÇ£own voices,ÔÇØ and who is and isnÔÇÖt entitled to tell certain kinds of stories.

In the past, this sort of grumbling over imperfectly woke books has sometimes grown into a five-alarm social-media fire replete with vote brigading, form-letter writing, and petitions to cancel publication. But whether Blood Heir might have eventually become a target of animus on the order of The Black Witch, American Heart, or The Continent, weÔÇÖll never know. Just as Twitter was beginning to fan the flames of the controversy, Am├®lie Wen Zhao ÔÇö who had been silent since before @LegallyPaige first accused her of plotting against book bloggers ÔÇö gave her first and (for now) last statement on the matter. She had not intended to evoke an offensive analogy to American slavery, she said, but she had nevertheless asked Delacorte not to publish her book.

ÔÇ£The issues around┬áAffinite indenturement┬áin the story represent a specific critique of the epidemic of indentured labor and human trafficking prevalent in many industries across Asia, including in my own home country,ÔÇØ Zhao wrote. ÔÇ£The narrative and history of slavery in the United States is not something I can, would, or intended to write, but I recognize that I am not writing in merely my own cultural context.ÔÇØ The statement continued: ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt wish to clarify, defend, or have anyone defend me. This is not that; this is an apology.ÔÇØ

Unsurprisingly, the response was wide-ranging and intense. Some (including Ellen Oh) lauded Zhao for her bravery, others derided her for cowardice, and many wondered aloud if the author had self-censored voluntarily out of fear┬áof a mob that would hound her until publication and beyond. For now, the future of┬áBlood Heir┬áremains uncertain ÔÇö and the Twittersphere rages on.