Once again, Vulture is speaking to the screenwriters behind the awards season’s most acclaimed movies about the scenes they found most difficult to crack. In Björn Runge’s The Wife, which was adapted for screen by Jane Anderson, Glenn Close makes a brilliant final push for the Best Actress Oscar in the film’s climactic scene. The film has slowly built up the marital tension between Joan (Close) and John Castleman (Jonathan Pryce) for an entire movie when Joan finally an unleashes a lifetime’s worth of resentments for being the uncredited genius behinds his Nobel-prize winning body of literary work. The scene pits two fierce intellectuals against one another, and Anderson had to find the right balance of wit, fury, and tenderness in a marriage-ending confrontation. Here’s how she cracked the scene open and exercised her own pent up frustration with Hollywood misogyny — all with a little help from Pip Close.

Meg Wurlitzer begins her novel in first-person voice through Joan, and at the very top of the novel Joan is pissed and sardonic and angry and saying all these things that movie Joan says at the end. In the early draft I took some of the dialogue from the book — from the actual fight scene — and then I started veering from it, making the anger and the things she says more of a surprise to Joan that she’s finally saying something she felt the entire time. That is the difference between the novel and the film. I wanted it to be a slow, slow burn.

Once Glenn came on board and we started discussing the scene in the rehearsal room before they shot the film, that’s when I did the real rewriting of the scene. Glenn is an incredibly insightful, thoughtful actress. We’ll go through a script literally line by line and analyze whether it makes sense to her character emotionally or on a meta level. We had a lot of discussions about the early version, because it’s a little one-note, just anger and bile and everyone is tossing things back and forth. Jonathan Pryce is another very intelligent actor, and the two of them and our director Björn Runge and I sat in the room and discussed it.

All I can remember is I madly wrote for a couple of hours, got the new pages to Glenn and Jonathon and Björn and watched them read it. And then Glenn saying, “No. No. It’s not there yet.” And I remember riding back to the hotel with Glenn in her car and her little dog Pip, sitting and petting Pip’s little white, furry head and my stomach was all in a knot and I was thinking to myself, “How am I ever in God’s name going to solve this scene and make it right and get it ready for them in the next day?” That feeling of panic as a writer, that deadline panic of “How, how will I ever solve this? I’ll never get it right, and they’ll never be happy.” I remember that, and having a little dog’s head to pat. The goal was to make this fight as real and, more importantly, as intimate as possible. And I really dug down into how a married couple who has been together for decades would tear apart their relationship. Her objective is to break free, and his objective is to keep her. So that week when I was there it took me three tries to get it to that final version. I went back to my room, opened up my computer and just wrestled it till I got the third one right.

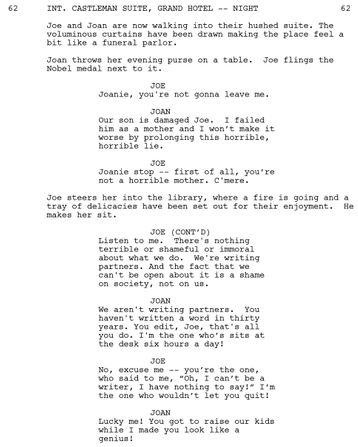

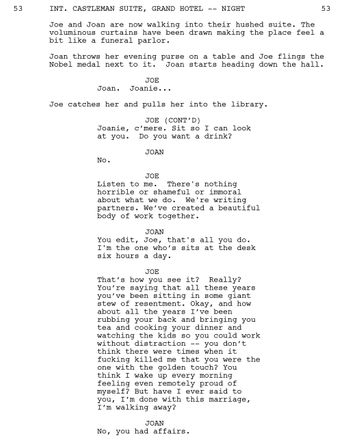

Scroll back and forth between an early and a final version of the scene here:

It was a real challenge, and there were times when I overwrote it. It was too much verbiage and too hard for Glenn and Johnathan to get their mouths around the words. I wanted to empathize with Joe’s character, because in the book he’s much worse. He’s awful, and her contempt for him is legion. But you don’t want to see that on film. The more horrible he would be, the less respect you would have for her. So that section of him justifying and complaining, I thought a lot about Amadeus and how painful it was for Salieri to have an artist’s heart but not to have the talent. That is Joe’s agony and tragedy. He has the heart and soul of a writer, but he doesn’t have the ability, and that section of him talking about “Look how I’ve supported you” is almost a way of saying, “Look what I’ve sacrificed!” That was essential, and Jonathan did such a beautiful job of delivering it.

What you learn when you’re collaborating with actors, and when it’s a piece of dramatic literature, is to cut down to the essential emotional beats. And I had the task of writing a genius, you know? She’s a Nobel Prize-winning writer, so intellectually she has to be incredibly sharp and insightful and precise. You know, it’s hard to write someone who’s brilliant and also to keep them human. I got to swing back and forth between those two elements, the cutting and witty and precise, and then helpless. So, instead of just a relentless screed against each other, I found those moments of backing up, of vulnerability, of Joan suddenly feeling helpless and saying, “I just want to take this dress off.” Then I wrote in that he starts unzipping her like any married man would, and that was essential to the scene, because really the film is not about victimhood. It’s about the agreements we make in a long-term marriage and how those agreements and arrangements work until they don’t anymore, until someone finally says, “I can’t.” What was really wonderful about the way Björn and Glenn and Jonathan approached this is they understood throughout the film to build a couple who really do love each other and have a long history together, so that the tearing apart is all the more impossible and painful.

Scroll back and forth between an early and a final version of the scene here:

That whole scene where she was flinging the books, I liked the visual element of the audience seeing this body of work lying around. Really, it’s not just about the infidelities. It’s about who owns what. Glenn talked about the basic agony of doing all the work and being unrecognized, and part of that agony is that she put up with his affairs, that she understood on a very deep and wifely level that his damaged ego compelled him to have these affairs. She just put up with it all these years because in the end she got to write. Then she looks at the ugliness of that and really knows it. When we’re in a bad situation for years, we never really want to acknowledge how bad it is to survive.

I’ll tell you, this movie is kind of a metaphor for me as a female screenwriter and director in Hollywood. All the decades I’ve worked in this business, I never really outwardly, verbally would acknowledge how sexist the industry is. Because if I did, I knew I would just stew in resentment and not do any work. Also, it would look unattractive, which is what we all worry about as women in an industry where we’re trying to maintain a professional profile. And with the film finally being made after 14 years and all the terrible sexist comments that were made to me about my screenplay way back then, it finally feels really good to acknowledge it. But I kept my mouth shut all those years, and now Glenn is up for an Academy Award and the film is being recognized not just by women in the industry, but by men. I now have respect for this script that those years ago I was told was awful and man-hating and a piece of crap. I don’t have to be furious and bitter. Finally I can just delight in it, but it’s the same feeling that Glenn’s character has in that final scene of, “I get to fucking say this! I get to finally say this is appalling. This is appalling what we’re doing!”

This film has been released just at the right time, and that happens with many pieces of art. If Beale Street Could Talk couldn’t have been made 14 years ago, and there are some really spectacular films that are out that have found their time. So, I’m really grateful it took this long.

Read an earlier draft of the scene below:

And read the finalized shooting script here:

Now see a clip from the scene in the finished film: