A few weeks ago, Vampire Weekend’s Ezra Koenig sat down with NPR to premiere two new songs from their upcoming album, including the dreamy “2021.” It featured Jenny Lewis and, unexpectedly, a sample from Japanese electro-pop demiurge, Haruomi Hosono. A legend in his home country thanks to his iconic group Yellow Magic Orchestra, as well as a half-century of trailblazing solo albums, Hosono is only just now getting his due in the West. Yes, Hosono had sought out Van Dyke Parks and Little Feat’s Lowell George in the early 1970s to produce his first band, Happy End, but most of his music didn’t resonate outside of Japan. But there were a series of reissues from the Light in the Attic label late last year, and Mac DeMarco covered his early hit “Honey Moon” (additionally, he’s been sampled by the likes of J. Dilla and Afrika Bambaataa over the years). But the Hosono piece that Koenig honed in on stood apart. “He made this music to be played in Muji stores in Japan in the ’80s,” he said. “This music was composed to be kind of ambient tone-setting music for your shopping experience.”

It was background music, or as the industry and YMO called it, “BGM.” And while that conjures strains of bland Muzak and inoffensive elevator music in the West, in Japan, such environmental music has a far more curious backstory. Fittingly, the label Light in the Attic released Kankyō Ongaku: Japanese Environmental, Ambient & New Age Music 1980–1990, a massive survey of such tone-setting music that, aside from its placid surface and gentle tones, reveals its tangled roots in Dadaism, Fluxus, the French New Wave, and Shintoism, as well as corporate largesse and hypercapitalism. So how, exactly, did the cloistered sound of Japanese environmental music become cool in the West?

New Age music has been proliferating in cool circles for almost a decade now, whether you dug Animal Collective’s sampling Zamfir, the renaissance of original pioneers like Iasos and Laraaji, 21st-century wizards like Oneohtrix Point Never or Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith, enjoyed Light in the Attic’s rehabilitative set I Am the Center: Private Issue New Age Music in America, 1950–1990. Or maybe you just had a hatha yoga soundtrack linger with you after class. But much of what was happening musically in Japan in the 1980s was closed off to Westerners, or more precisely, Western hipsters.

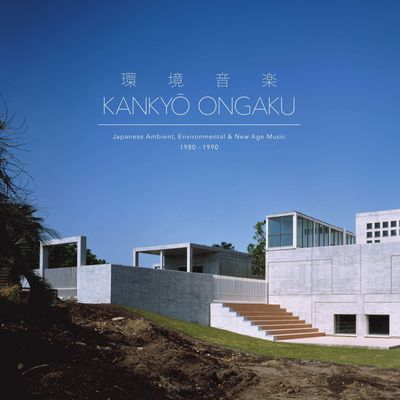

In July of 2010, Portland-based musician Spencer Doran uploaded to music obsessive Root Strata site a mix entitled Fairlights, Mallets and Bamboo. Drawing from this peculiar and under-explored decade of Japanese music, its popularity led to a sequel, as well as one focusing on Japanese environmental music, Music Interiors, with a photograph of esteemed Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki’s own living room for its cover. “Music Interiors was a conscious attempt to examine the ways that ambient/environmental music was interwoven with the corporate sphere in the bubble era,” Doran recently told me via email. “The social conditions of the time not only helped to support this music financially, but also manifested its necessity, with its use as a tool for lifestyle management under hypercapitalism.” It’s this latter mix that Doran used as a blueprint to assemble Kankyō Ongaku, the track selection mirrors much of that original mix in terms of artists, if not selections. A photo from the Maki-designed Iwasaki Art Museum adorns the cover.

In the wake of Doran’s mixes, more and more Americans began to seek out these heretofore-unheard artists. Few if any of them had ever been released in the U.S., and little of this music had been reissued in the subsequent decades in Japan. So the curious turned to YouTube to try to hear more. One of the most revered artists from these mixes was a little-known percussionist named Midori Takada. She had put out but one album in 1983 before disappearing from view. That magical album, Through the Looking Glass, was uploaded to the platform and soon accrued millions of views. So did a mysterious album from an artist called Mariah, full of thundering Japanese percussion and a female vocalist singing in … wait, is that Armenian??! The artist behind Mariah, saxophonist Yasuaki Shimizu, had another album, 1982’s Kakashi, which also topped 1.2 million views. All three albums have since been reissued, with Takada and Shimizu enjoying revived careers leading to tours in the U.S. and Europe, something all but inconceivable back in 2010. And a cottage industry of labels has seemingly sprung up like mushrooms overnight, from Brooklyn’s Palto Flats and U.K.-based LAG Records to French imprint WeWantSounds and Switzerland’s We Release Whatever the Fuck We Want Records (or WRWTFWW for short). Doran’s own imprint Empire of Signs reissued the exquisite Music for Nine Postcards by one of the era’s most profound thinkers of such sound, Hiroshi Yoshimura.

For reasons not quite clear, the YouTube algorithm began recommending more and more Japanese music of this sort to anyone adventurous enough to let their AutoPlay queue up a few selections. Almost any instance of listening to a rare electronic or jazz album might soon send you to the East. SPIN’s Andy Cush wrote an essay last year about giving himself over to the algorithm, detailing how his search for an obscure British post-punk album soon sent him down such a rabbit hole. Most times it put him before the feet of a true master like Yoshimura. “Now, I listen to Yoshimura’s music almost every day, both because I find it tremendously moving and because YouTube won’t stop playing it,” he said. It led to millions of views on the platform for Yoshimura and rapturous user comments, not to mention astronomical prices for his albums.

“I think YouTube gets far too much credit in the narrative,” Doran said, pointing not to the algorithm but the artistry behind it. “It’s music of high artistic merit, and that alone is the root reason why people gravitate to it. So much of this music was so internal within the Japanese market until very recently, and I believe that if it had been in global circulation earlier, these musicians would already have been canonized.”

Which isn’t to say that Japanese environmental music isn’t informed by the West. As Paul Roquet noted in his 2016 book Ambient Media: Japanese Atmospheres of Self, a paradigm-shifting event in postwar Japan occurred when Louis Malle’s 1963 film Le Feu Follet opened in the country. Malle’s somber film featured the contemplative piano music of turn-of-the-century Dadaist composer Erik Satie, including his most famous pieces, the minimal and evocative Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes. By the next decade, critic and early Fluxus member Akiyama Kuniharu staged an Erik Satie concert series in Japan, which featured Satie’s music played by pianist Aki Takahashi, as well as poetry readings, lectures, and more. It ran for over two years. Soon Satie’s meditative work infiltrated everything from theater productions and violent cop movies to luxury-car commercials, what the media deemed a “Satie boom.”

Japan’s “Satie boom” soon dovetailed with a few other factors. One was the release of Brian Eno’s ambient-defining Music for Airports, itself informed by Satie’s notions of furniture music and — as the notes stated — “as ignorable as it is interesting.” It was followed a few months on by the introduction of Sony’s first Walkman in 1979. Rather than be tethered to home stereos, now any sort of music could conjure entirely intact personal worlds for a listener as they wandered about an urban landscape.

Haruomi Hosono was already a superstar in his native Japan thanks to the smash success of Yellow Magic Orchestra, but he found himself dealing with the perils of pop stardom by turning to non-pop. “When the Ambient series came out, the music had a very psychological, healing effect on me, sort of like a tranquilizer,” he said in an interview. “It was incredibly refreshing.” With an array of new musical technology at his disposal (like the LinnDrum, MC-4 sequencer, Prophet-5 synthesizer, and early samplers), when YMO went on hiatus Hosono began to create his own ambient music in earnest. Hosono wasn’t alone. Kankyō Ongaku shows a generation of Japanese artists attuned to such unobtrusive yet transportive sounds, from progressive rocker turned healing-music impresario Akira Ito to future Studio Ghibli/Hayao Miyazaki soundtrack composer Joe Hisaishi.

This same time period also coincided with Japan’s economic miracle, a three-decade-long boom that hit its stratospheric peak in the 1980s. At a period when corporate sponsorship would have been anathema to American artists, Japanese artists welcomed it. “The reality of the relationship that corporations had with these artists was that they were often given an unheard amount of creative control — because they were so flush with cash, corporations funded the arts in this weird neo-Medicean patronage model,” Doran explained. So Yoshimura’s 1984 ambient album AIR was sprayed with the latest scent from Shiseido, Yasuaki Shimizu made music for Seiko watches, Takashi Kokubo recorded a dreamy album to be bundled with Sanyo’s new line of air-conditioning units, and Hosono made shopping music for Muji.

These compositions could peddle consumer goods and were themselves a consumer good, providing ready-made environments for its customers. Why that resonates so much now can’t quite be pinpointed, but in some aspects, the onrush of new and invasive technologies in Japan during the ’80s finds parallel to our modern life, what with never-ending social media, the exhausting gig economy, neoliberal anxiety, and a sense of capitalism run amok. Spend a few hours immersed in Kankyō Ongaku and it’s hard not to feel a sense of serenity amid such a hectic pace. It is, at the very least, eerily similar to something pianist Aki Takahashi would hear after her Satie performances from strangers on the street in Tokyo: “Even when I am tired, when I listen to Satie my mind goes blank, my spirit relaxes, and I can go on working.”