It has been argued that SoundCloud rap is a punk-rock moment for hip-hop. It’s an offbeat assertion — hip-hop’s “punk” phase ran concurrently with rock’s punk phase in 1970s New York City, where the rock kids and the arbiters of what would eventually become rap music shared key figures and an amateurish, revolutionary zeal as they figured out how to play their instruments on the fly. But the root of the assertion, that the rising rap stars of the back half of this decade are more interested in expression than technique, stands. If SoundCloud is a punk moment for rap, Lil Pump is Suburbia, the 1984 feature by American film director Penelope Spheeris that dramatizes the ’80s L.A. hard-core scene through anthemic show footage and Shakespearean melodrama offstage. Everyone is too young, and there are too many hard drugs around. The same quest for freedom that gives the kids a sense of limitless power and possibilities becomes the pathway to their undoing. Watching Lil Pump elevate his national profile through a series of reckless, infectious trap bangers, then discover his boundaries via worrying run-ins with law enforcement, is a reminder that a possible consequence of living a life on the margins is teetering over the edge.

Harverd Dropout — Lil Pump’s sophomore studio album, following 2017’s slight, successful self-titled debut — is what we talk about when we talk about “mumble rap.” The slurred words, speedy delivery, and machine-gun repetition of Pump’s breakthrough singles “D. Rose” and “Gucci Gang” are the blueprints for the whole album. The script doesn’t deviate. The talking points don’t change. Lil Pump does drugs. Lil Pump hates school. Lil Pump is sleeping with his teacher. Lil Pump is sleeping with your girlfriend. Lil Pump is giving your girlfriend drugs. If you came to the album with no prior knowledge about life of the Florida rapper, born Gazzy Garcia, the new album doesn’t offer much. The lyrics are wall-to-wall antics, like a cartoon. But you don’t come to SpongeBob Squarepants to learn about the migration habits of fish or the plight of the coral reef. The success of the thing hinges on the outrageous distance it’ll travel to get a laugh out of the audience. Harverd Dropout’s best songs are its most depraved. If you’re able to get around the low-grade horror of hearing a kid barely old enough to buy cigarettes cracking wise about preferring popping pills to eating food, it’s possible to receive these songs as devilish little wish-fulfillment scenarios, like Eminem murder fantasies or Migos lines about climbing mountains to meet drug kingpins.

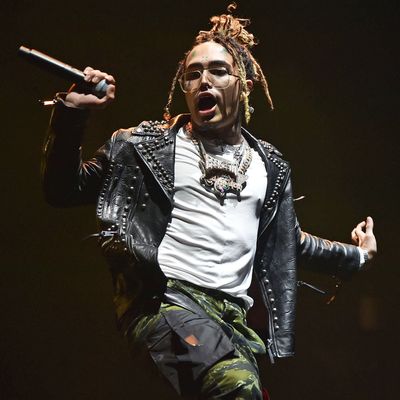

The charisma that puts tracks like “Drop Out,” “Esskeetit,” and “ION” over the top doesn’t always stick. Pump has only been rapping for three years, and at times, he falls into familiar patterns. “Off White” is a Chief Keef knockoff down to the “bang, bang” ad libs. “Too Much Ice” sees the young rapper mimicking the Migos in anticipation of an appearance from Quavo, whose quick, smooth verse at the end makes the marquee artist feel like the opener. In addition to Migos and Chief Keef tributes, Dropout borrows liberally from the hailstorm of ad libs of Playboi Carti’s Die Lit and the unflinching absurdism of Lil B. Elsewhere, guests elevate Harverd Dropout at the cost of making Pump look smaller. Lil Uzi Vert, the brat rap king so bored and disaffected that he’s functionally retired at 24, contributes a quick verse to “Multi Millionaire” that outdoes the younger artist without doing much heavy lifting. Kanye West — here continuing his campaign of guest features on all the youngest, wildest rappers’ studio albums — leans into the sex-obsessed id of “Hell of a Life” and “I’m in It” on Dropout’s curt, horned-up hit single “I Love It.” 2 Chainz flashes his strip-club rap crown in a lively spot on “Stripper Names.” Lil Pump is still figuring himself out as a rapper, cribbing ideas from influences and bouncing lines off established artists, but he’s an exciting prospect because beneath the gimmicks, you can hear an offbeat rhymer with solid foundations.

The picture that Harverd Dropout paints, though, even accounting for poetic license, seems scary. Lean, Xanax, molly, and coke don’t make a steady diet. This decade’s pet party drugs are taking a toll on the hip-hop community. Balance is crucial. From the end of 2017 to the end of 2018, Lil Pump crashed a car, discharged a gun in his home on accident, got kicked out of Denmark for flipping off Copenhagen police after getting caught with weed, got hit with tear gas onstage at a show in the U.K., and had a worrying shouting match with police after being thrown off a flight in Miami for disorderly conduct and possible ownership of luggage with drugs inside. (Charges from the airport incident were dropped this week.) As much as Pump’s career is a story of youthful daring — last winter, the rapper and his lawyers successfully voided a record deal he signed at 16 and resigned a reportedly multimillion-dollar contract with more and better rights — the same carelessness holds the power to destroy everything he’s building.

Times are strange. The youth are getting restless. They crave heroes who make a farce out of this age by doing whatever they want and throwing it in the faces of anyone who stands in their way. But you can only party so hard before your body riots. You can only dance around the law so much (especially as a person of color and a hip-hop artist with pink dreads and face tattoos) before it catches your scent. It happened to the punks at the end of the ’70s, and it’s happening to the SoundCloud rappers of this decade at an alarming rate. As much of a laugh as Harverd Dropout can be when it wants, the worry that Lil Pump is going to bungle this multimillion-dollar ride is hard to shake.