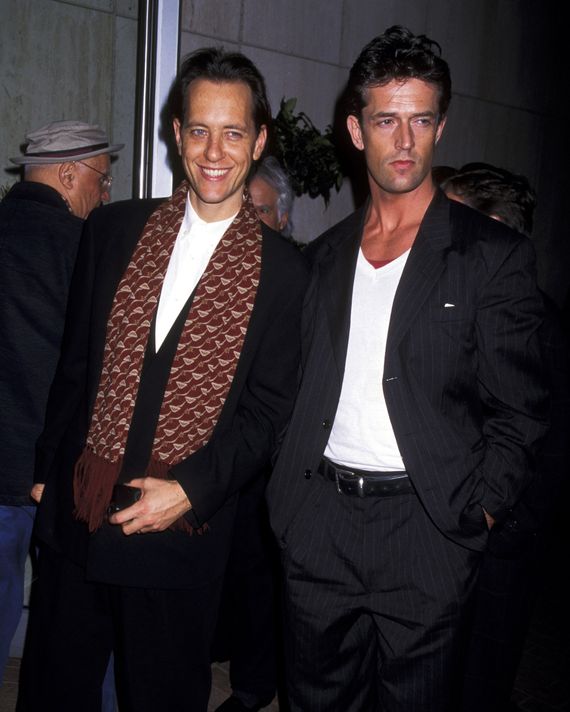

Marielle Heller’s Can You Ever Forgive Me? is a portrait of a world that, while it hasn’t quite disappeared, has certainly faded somewhat. The movie’s vision of 1991 New York is familiar, thanks in part to Seinfeld reruns, but it’s also a reminder of how much the city has changed in the past 30 years: This is a Manhattan where an unemployed writer can still afford a one-bedroom on the Upper West Side, and where the friends and lovers lost to the AIDS crisis are still fresh wounds. It seemed fitting, then, that when the movie’s Oscar-nominated supporting player Richard E. Grant came to town, to ask him about his own strongest memories of Old New York. Here they are, in his own words.

The first time I came to New York was 1988. I was doing the first movie I ever made in America, a horror movie called Warlock. It was shooting in Boston and L.A., and I had time off to come to New York in between. It felt like landing in Oz. The sheer ferocious self-confidence of people in the 1920s, building these skyscrapers that nobody else in the world had done, was awe-inspiring. There’s the obvious cliché that having grown up seeing so many movies set in New York, you feel like you’ve been there before, but nothing really prepares you for the scale of it, and the speed of it. I felt like I’d been literally plugged in, both fingers and toes, into an electric current.

The Village Voice and the Algonquin Hotel

I remember the Village Voice newspaper was in the university library when I was training as a drama student. Reading about all the people at Studio 54, and the stuff that was going on in the city, it seemed so erotically charged and exciting. I had an idea that New York was just about the most fantastically decadent place on the planet. But it wasn’t quite that when I finally got here in 1988. I was much older. The first place I stayed was the Algonquin Hotel. Having read Dorothy Parker, and the legend that has accrued around that group of people who frequented the place, everything is charged with memory and expectation, and the people that I subsequently met and worked with.

Elaine’s

I remember the first time I went with Robert Altman and his wife, both of whom are now gone, to Elaine’s. I was absolutely astonished how disgusting the food was. It was inedible. But it was such an institution, and I’d seen it in so many Woody Allen movies. She was so friendly to the Altmans, and therefore by proxy, me. I thought, You haven’t come here for the food; you’ve come for a corner of New York bohemia.

Trattoria Dell’Arte

The antipasti bar at Trattoria Dell’Arte opposite Carnegie Hall on 7th and 59th is a place that I’ve gone back to again and again. It’s noisy, and its food is really good, and you always feel there’s a huge theater crowd surfing in and out of there. And it’s Italian food. What’s not to like? It’s not cutting-edge, and the food is not fucked about with. There’s no foam or steam, or test-tube stuff at anybody’s table.

The Ziegfeld Theater

Altman lived on the Upper West Side, and the premiere of Prêt-à-Porter, or Ready to Wear as it was called here — which was a disastrous movie — was at the Ziegfeld Theater. I just walked past there yesterday, and I saw that it’s now no longer. I thought, Oh my God. I feel like Rip Van Winkle. I’m walking around, I said to my daughter, “That used to be …” and she’s like, “Yeah, yeah, yeah.”

Times Square

All the area around Times Square and 42nd Street, there were peep-show bars and strippers, and pimps and hustlers. It felt like a latter-day version of Guys and Dolls: neon-lit seediness, people hustling and trying to earn a buck out of you. And there were a lot of X-rated movie places. None of that exists now. But that danger, edge, grittiness, whatever you call it, because of the very nature of human beings, it erupts somewhere else. I remember Brooklyn was the place Neil Diamond and Barbra Streisand famously spent all their youth trying to get out of. Then when I was on Girls, Lena Dunham kept telling me about Williamsburg. In London it’s moved to East London, or east of East. And as I’ve got older, I’ve gone further west and west. That’s how it works. The pendulum has swung. Nothing’s so desperate as old people trying to hang on to keeping trendy, when they’re clearly past their sell-by date.

The Meatpacking District

In 1991, I went to visit Sandra Bernhard, who I’d just worked with on Hudson Hawk. She lived in the Meatpacking District, and I saw men on street corners, which so shocked me. In the richest, most densely populated square mile practically on the planet, there were men dying of AIDS in what looked like their early 20s, 30s, and 40s, saying that they’d been abandoned by God, by Medicare, by their families, could you give them any money. Even though it’s only a historical blink away, it’s made an indelible impression of how isolated, lonely, and destitute that whole generation of men were who died of AIDS.

The Chelsea Hotel

I hosted a series called Hotel Secrets, about the history of the most famous hotels on the planet for Sky90 channel in England. We filmed at the Chelsea Hotel a month before it was turned into luxury apartments. Interviewing the people there who were being ousted by the landlord, they told me the heating was turned off, or leaks suddenly appeared where they hadn’t before. There was a real sense of subterfuge. Big business coming and saying, We no longer want rent-controlled people living here in a state of bohemia in this part of the city.

Rizzoli Bookstore

Re-creating these corners of frayed-edge New York in the early ’90s for Can You Ever Forgive Me? was a real treat, because we went into the bookstores where Lee Israel and Jack Hock really operated. There’s nothing for me like the smell and the atmosphere of bookstores. Especially ones that have been there for a long time. I’m always amazed at what you can find online, but I’ve never had that same experience discovering books online in the way that I do if I’m literally in a place where there are shelves and stacks of them. I have a nostalgic longing that they won’t disappear completely, but I’m on quicksand with that one, because they are closing as we speak. My favorite is Rizzoli. It’s on Broadway, and it has huge, large-scale coffee-table books of art and design and fashion and photography. All that stuff that you don’t regularly find. It just seems emblematic of everything being bigger and on a greater scale in America than anywhere I’ve ever been. I love going to that bookstore.

The subway

I had seen Taxi Driver, and I’d seen French Connection. I thought I was probably gonna be murdered on any street corner. Even in 1988 the subway was a hairier kind of experience. I’d go down there thinking, Will I get mugged? But I love using public transport. I do it in London every single day. In New York I go on the subway all the time, because it’s so much faster, and also because, more than anything, every single person now has a mobile phone, so you can just sit and blatantly stare at people. Pre–mobile phone you had to be more discreet in staring, because people would notice, but now everybody’s oblivious to everything.

Traffic signals

The other thing that I can remember being so struck by in 1988 was that all the traffic lights’ signals used to have “WALK” or “DON’T WALK.” I thought that was unequivocal. Either you’re doing it, or you’re not doing it. You’re either a success on Broadway, or you’re closed and you’re a flop. Now it’s the hand, you don’t get “WALK” or “DON’T WALK.” I miss seeing that, because it seemed so quintessentially New York in attitude.