ItÔÇÖs strange to talk about Steven Seagal in 2019. In 1988, when he broke into Hollywood swordfighting bad guys in driveways? Sure. In 1991, when he was arguably the worst host in the history of Saturday Night Live? Okay. In 2006, when he released the appalling blues guitar album Mojo Priest with the first single ÔÇ£Alligator Ass?ÔÇØ Fine. But today? What reason could there possibly be? Well, two years ago, Seagal ÔÇö close personal friend to Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin ÔÇöwrote a novel that is both urgently relevant to the current state of our union and completely batshit insane.

Seagal, a martial-arts enthusiast from Michigan, parlayed a West Hollywood dojo into starring roles in more than 50 action movies, from Hard to Kill to Out for a Kill to Kill Switch to Driven to Kill to Contract to Kill, and with each one, his shiny black widowÔÇÖs peak gets sharper and his husky whisper less intelligible. Whether his character is ex-CIA or ex-Special Forces or ex-Black Ops, he is first and foremost Steven Seagal, an environmentalist aikido master who does not believe in violence and will absolutely murder you brutally.

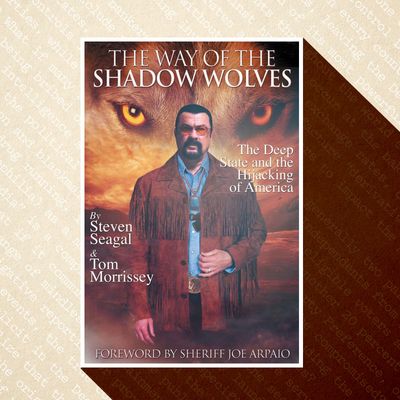

It reflects well on the nationÔÇÖs book-buyers that none of this guarantees a fiction best seller. Published in October 2017, The Way of the Shadow Wolves: The Deep State and the Hijacking of America made basically no impact on the literary world but did come up as the butt of a joke on podcasts or among comedians, usually white men. No one claimed it was good, but it was at least a new lens on Seagal, a man who commanded movie screens, cable TV screens, and straight-to-VHS screens for three decades. Now age 66, the B-movie lead should have faded into comfortable obscurity, yet here I am in 2019 declaring that he has written a book and that, against my own better judgment, I have read it.

ThereÔÇÖs a lot to unpack. LetÔÇÖs start with the cover. Behind a dusty red desktop screensaver image of a desert, the sky is not a ÔÇ£skyÔÇØ but a huge wolf face. In the foreground (but strangely out of focus) is SeagalÔÇÖs own floating bust, lifted from a recent photo, complete with orange-tinted glasses, jet-black goatee, and incredulous squint, and adorned with clip art: a tasseled suede jacket, chunky medallion/badge, belt buckle, and the handle of a cartoon gun.

Open the cover and you find a dedication to Native Americans, the tribal police, U.S. Marshals, and all like-minded folk who recognize the threat of the deep state. Turn the page and you see an ominous disclaimer:

This is a work of fiction and any resemblance to anyone living or dead is purely coincidental.

But always remember that the truth comes in many forms.

You see what IÔÇÖm saying about the blurred line between reality and fantasy. Then there is a foreword by Sheriff Joe Arpaio ÔÇö yes, that Joe Arpaio, the former Arizona lawman known for gleefully rounding up anyone a shade darker than ecru and imprisoning them in draconian tent cities, a man Rolling Stone called ÔÇ£AmericaÔÇÖs meanest and most corrupt politician.ÔÇØ

ArpaioÔÇÖs foreword is one page long. He insists that this story you are about to begin (which he himself certainly did not read) ÔÇ£is less than a hairÔÇÖs breadth from the frightening truth of what is actually happening today in America.ÔÇØ The action of Shadow Wolves takes place entirely in Maricopa County, Arizona, Sheriff JoeÔÇÖs home turf. Linger awhile on this page. How many novels are introduced by a disgraced 86-year-old ÔÇ£cowboyÔÇØ of the American West?

Please skip SeagalÔÇÖs preface, a gag-inducing queso of political buzzwords (ÔÇ£fake news,ÔÇØ ÔÇ£mainstream media,ÔÇØ ÔÇ£most history is a lieÔÇØ) in which every single sentence is phrased as a question. It should be noted that Seagal co-authored Shadow Wolves with ghost writer Tom Morrissey, age 80, who identifies himself on the book jacket as a retired chief deputy U.S. Marshal, martial artist, musician, author, political leader, and activist. (Although Sheriff Joe resoundingly lost his Republican primary campaign for Senate last August, Tom Morrissey was at the same time elected mayor of a small Arizona town. No word on SeagalÔÇÖs political aspirations in the Grand Canyon State.) For the sake of comedy and simplicity, letÔÇÖs attribute the words in the book to Seagal himself.

With that business out of the way, the story begins in earnest. We meet our protagonist, a Native American tribal police officer and former Marine named John Nan Tan Gode, clearly a Seagal avatar: a ÔÇ£big lawmanÔÇØ who speaks like a ÔÇ£philosopher poetÔÇØ in a ÔÇ£fierce whisperÔÇØ and cuts a silhouette that could be mistaken for a saguaro cactus (not an exaggeration).

SeagalÔÇÖs attitude toward race is unique among artists of page and screen. On human Earth, he is functionally a white man from Michigan, and he endorses offensive white-constructed minority archetypes like the ÔÇ£Magical Negro,ÔÇØ with their folksy spirituality and connection to the land. But ÔÇ£Magical NegroÔÇØ has the word ÔÇ£magicÔÇØ in it, so of course Seagal canÔÇÖt let another character have it. He wants to be that guy too.

John Gode/Steven Seagal is both a police officer at the top of the entrenched power structure and a Native American prince of the spirit world with access to powers no other man can even comprehend. This is the fundamental oxymoron of the Seagal-iverse. Few other action stars of his ilk ÔÇö Van Damme, Stallone, Schwarzenegger, Gibson, Norris ÔÇö would ever play a nonwhite hero, much less write themselves as one.

Gode is that rare Native American protagonist who exoticizes himself. At one point he says he is of Mohawk heritage, later he says Apache, and though he is certainly the most spiritual and gifted of some tribe or other, he makes a point of mentioning that ÔÇ£RedskinsÔÇØ is a fine thing to name your sports team.

We meet Gode in a theater, watching a screening of what seems to be a three-minute documentary on the Trail of Tears, a story so moving that he slowly backs out of the theater altogether. Outside, he begins a vague spiritual dance, chanting and shaking his fist in the air, until he is approached by a wolf from the underbrush. The wolf ÔÇ£kisses him on the forehead.ÔÇØ

Twice in the course of the story, Gode receives a forehead kiss from a wolf. Twice he pulls a gun on his grandfatherÔÇÖs ghost. Gode is one of the Shadow Wolves, ÔÇ£those who were trained in the old ways because they had the natural instincts of a wolf and could do things like track people and animals based on factors that others couldnÔÇÖt see or smell.ÔÇØ The Shadow Wolves are a real federal law enforcement unit of Indian officers, operating since the early 1970s, who track smugglers along the Mexican border within the Tohono reservation. But their role in the fight against deep state operatives within the U.S. government doesnÔÇÖt appear to be documented. (Or is it?)

Gode discovers a different kind of ÔÇ£bad hombreÔÇØ coming over the border: OTMs, or ÔÇ£other than Mexicans,ÔÇØ who are actually Middle Eastern people in a terrorist caravan (reminder: this was written two years ago). Gode cracks the case using his preternatural connection to the spirit world as well as just finding a shit-ton of Korans all over the desert. (Could this be the source of the infamous ÔÇ£prayer rugÔÇØ meme?)

The jihadists intend to come up from Mexico through the American Heartland until they reach their destination of ÔÇ£Ithica, New York.ÔÇØ (Seagal must be referring here to Ithaca, that liberal enclave of twee tapas restaurants and millennials who own looms.) Gode canÔÇÖt alert higher U.S. authorities, because of course the CIA and former President Obama are colluding with the bad guys.

As a writer, Seagal excels at car chases and shoot-outs and car-chase shoot-outs; he never forgets to note how much dust our protagonistÔÇÖs SUV is kicking up. The action sequences read like they were lifted directly from the goldenrod pages of Half Past Dead or Exit Wounds: full of Sig Sauers and bon mots. The antagonistÔÇÖs motivations never make much sense. All we need to know is that they are the bad guys and they are definitely in cahoots.

John Gode does not have sex, but he does pull a gun on his girlfriend, a fellow Shadow Wolf who is for some reason always shaking debris out of her long hair. It seems impossible for Seagal to imagine relating to a female person, which isnÔÇÖt surprising, given that he is the subject of some of the grossest and most credible sexual-assault allegations of the #MeToo era.

Seagal does have notable strengths. Character names, for instance. GodeÔÇÖs friends include Maurice ÔÇ£ScottyÔÇØ Random, his sidekick ÔÇ£Noche,ÔÇØ a casino security guardÔÇôslashÔÇôdeep cover DEA agent named ÔÇ£Sunday,ÔÇØ and a wayward youth named ÔÇ£Sweet Tooth.ÔÇØ He also has a way with similes:

ÔÇ£He had a heart as empty as a hollow cave where nothing dwelt, ever.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£His stomach was sinking like the first car on the steep downward side of a tall roller coaster.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£The big man moved completely out of his way like a cloud riding the evening wind.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£Sunday had an accent similar to the late character actor Chief Dan George.ÔÇØ

ItÔÇÖs difficult to say for sure what really happens in this book or how it ends. It is a poorly written story from a deluded mind. It would be perfectly acceptable to conclude that Shadow Wolves has no value and accomplishes nothing. But since IÔÇÖve bothered to dissect it in such detail, and I donÔÇÖt want to admit IÔÇÖve wasted my time, let me offer a different conclusion: What Seagal has done here is take the next step in the evolution of the written word, and define a new era of art in general.

More than a century ago we entered the Modern era of art, philosophy, and culture, shaped by the entry of science and industry into daily life. We could investigate and experiment and discover objective truths. If we could understand the world, then we could improve it, perfect it. In books, our narrators were omniscient, they knew more than we did, they were smarter than us and they knew where the story would end.

Two World Wars later, we lost that faith. We hadnÔÇÖt created a perfect world: Science and industry were just bringing us better ways to destroy ourselves. Our narrators became unreliable, they had biases and flaws and blind spots. They could mislead us, intentionally or not. The truth became subjective. If no one knows anything about anything, really, what do we have the authority to write about? Only ourselves. Suddenly we were drowning in authors named Matt writing characters named Patt. We were reflecting on ourselves and we were skeptical. This was Postmodernism.

Steven Seagal crashes through these cultural developments like Kool-Aid Man with a katana. He gives us something beyond the unreliable narrator: an unreliable author. He has never asked himself, ÔÇ£What is real?ÔÇØ and doesnÔÇÖt feel the need to start now. He accepts a world that doesnÔÇÖt make sense and creates a fictional space by breaking rules he doesnÔÇÖt even see. ItÔÇÖs a lovely kind of self-hypnosis: to create your own truth and believe it utterly. To ignore the intelligence agencies, the statistics on illegal-immigrant crime and border crossings, the indictments approaching. To lie to yourself without realizing it.

Maybe this is what comes after Postmodernism. Characters written by a deranged author, children of a distracted god, not looking for the answers to questions theyÔÇÖve never heard. Opening their mouths soundlessly, walking by mirrors with no reflection. Happy and already dead.

Anyway  two stars?