The Matrix was the first shot fired in what’s now considered a benchmark year for American movies — 1999, the year that brought us Being John Malkovich and Magnolia, The Sixth Sense and Office Space, Fight Club and The Blair Witch Project and Election. And although few would claim it was the best of the bunch, it has worked its way into our thinking — for better and, unmistakably, for worse — as few other pieces of pop culture have done. We may talk about all those other movies. But Morpheus was right. In 2019, we are living in the Matrix.

Or, you know, maybe we’re not. Maybe in 2019, we just like to say things like “We are living in the Matrix” — and that may be the truest and deepest influence of a movie whose high-flown paranoia has insinuated itself into the way we live now. In an era when the president’s lawyer can go on TV and splutter, “Truth isn’t truth!” as if it’s something everyone should know, and endless speculative conversations proceed not from “What is reality?” but from “What if we’re living in a broken simulation?,” The Matrix is omnipresent — amazingly so, given how little we still talk about the actual movie. It’s not that the film was prescient. It didn’t anticipate our world. But it anticipated — and probably created — a new way of viewing that world. And, just as “Madness is the only sane response to a crazy world” fiction like Catch-22 had done a generation earlier, it granted everyone permission to refuse to contend with reality by deeming that refusal a form of hyperawareness.

To revisit The Matrix 20 years later is to make a jolting discovery almost immediately: It’s not that complicated! A lowly computer hacker (Keanu Reeves’s Neo) — a drudge, like so many late-’90s protagonists — is pulled into a pre-hashtag resistance he didn’t know existed against a system he didn’t know enslaved him. The rebels offer him enlightenment, but at a brutal price; he has to lose all delusion and realize he is literally part of an immense, systemic machine, doing the bidding of, well, take your pick: The Man. The Establishment. Corporate Overlords. The Government. The System. And only by knowing can he hope to be rescued from it. The plot is pretty basic, and the politics are alluringly, perhaps dangerously, viable for anyone of any ideology who feels pissed off. Few arguments have found themselves more adaptable to this moment than “You’re getting screwed by a world you didn’t invent and can’t see, but the good news is that the cure is just willing yourself to see it.”

For all the fan pages, the long and winding Wikis, the nods to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and to French critical theory, the hours upon hours of dauntingly labeled “philosophers’ commentaries” that adorn the Blu-rays, the original movie itself is, in some ways, as plain as the green cursor blinking on a black screen that, quaintly, begins it. In memory, the premise of Lilly and Lana Wachowski’s breakthrough film was an elaborate, wordy, barely comprehensible piece of world-building. But in truth, The Matrix gets most of the explanatory stuff out of the way in a few efficient strokes in its frontloaded first third so that it can get to the combo heist-movie–chase-movie–Sneakers–meets–Tron–meets–Mission: Impossible action flick that it becomes.

Laurence Fishburne’s Morpheus lays it all out. “The Matrix is everywhere. It’s all around us,” he explains to Neo. “It is the world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you to the truth … that you are a slave, born into bondage … in a prison that you cannot touch … Unfortunately, no one can be told what the Matrix is. You have to see it for yourself. You take the blue pill, the story ends, you wake up in your bed. You take the red pill, you stay in wonderland and I show you how deep the story goes.”

And there you have it: For all the ways in which it is subsequently elaborated on, that’s really all you need to know to “get” The Matrix and to get everything, both benign and insidious, that it has spawned. In those brief screenwriting gestures, the Wachowskis concocted the perfect one-size-fits-all combination of flattery, paranoia, anti-corporate wokeness, libertarian belief in the primacy of the individual, and ideologically nonspecific anger at the system: a “Wake up, sheeple!” for its era and, even more, for ours. The film has spawned only one piece of durable slang — “Take the red pill” (the uses of which range from the jokey to the horrific) — but its attitudes have worked themselves into and, arguably, toxified much of our discourse. We live, today, in the anti-reality world The Matrix built.

Before looking at that, though, it’s worth glancing back at the world that built The Matrix. For all its deep/stoned dorm-room Big Idea underpinnings, the movie was heavily steeped in the pop culture that preceded it. America tends to buy into one dystopian Hollywood fantasy at a time, and that fantasy can hang on for a generation or longer. At the time The Matrix opened, the dominant fantasy had, for the previous decade or so, been James Cameron’s The Terminator and its sequel. “Robots and computers are eventually going to take over and turn against us” was a narrative to which the Wachowskis’ film tipped its hat almost overtly: It’s essentially The Matrix’s origin story, acknowledged when Morpheus tells Neo that the rise of artificial intelligence spawned “a race of machines — we don’t know who struck first, us or them.” The Matrix replaced The Terminator’s “This is coming and you can’t stop it” with the logical next step: “This happened already and you don’t even know it.” In that, it drew from the other prevailing dystopic hit of the time, The X-Files, which was then at the height of its popularity, in its sixth season of advancing the premise that the vast majority of people were unknowing puppets in an alien-run world that was unseeable by them. The series explored that premise through the dichotomy of a believer and a skeptic; The Matrix, whose creators were up front about its being their version of a quasi-religious “salvation narrative,” changed it to the enlightened and the yet-to-be-converted, appropriating The X-Files’s opening slogan, “The Truth Is Out There,” almost intact. “What is the Matrix?” Neo asks Trinity. “The answer is out there,” she says.

Shrewd scavengers, the Wachowskis didn’t stop at The Terminator and The X-Files; they grabbed the idea of a rusted-out future and evil faceless corporate overlords from Alien and some future-noir flourishes from Blade Runner, and Hugo Weaving’s sunglassed Agent Smith is nothing if not a Man in Black. Neil Gaiman’s Sandman had already been around for a decade, and the Wachowskis are said to have told Fishburne to play their Morpheus like Gaiman’s Morpheus. But The Matrix isn’t just cleverly constructed out of spare parts. The Wachowskis added two important ingredients of their own: a sense that the only path to understanding is through a profound mistrust of everything that is put in front of you and a veneration of the stay-at-home hero. The first protagonist we see in the film isn’t Neo but Trinity, looking phenomenally badass as she sits working at a terminal, only raising her hands in stone-faced surrender when there are literally guns pointed at her back. The Matrix was the first movie to make sitting down and jacking in a renegade move and a form of kick-ass action, and it did so presciently, at the dawn of an era when more and more people would start to live on, and through, the internet, where it’s always easy to give in to the intoxicating effects of knee-jerk skepticism. The film ends with a Whoa, dude! moment in which we see Neo emerge into a very 1999-looking urban streetscape. This whole thing you’ve been watching? It could be happening in our world!

Even the Wachowskis may not have realized how much they were onto with that. Over the next few years, the real world would provide ample opportunity for people to turn their film into the foundational text of a frighteningly thorough and self-adoring denial of whatever was in front of their noses, which roughly translates as: Reality is fake and I don’t have to listen to anyone about anything (plus maybe I know karate despite never having studied it). Nineteen ninety-nine ended with the endless run-up to Y2K, which, although it ceased to be interesting to most people by about 12:03 a.m. on January 1, 2000, nevertheless provided ample fuel for speculation about the sentience and sheer power of machines. The following year brought the disputed presidential election; 9/11 happened ten months later. With each event, the ranks of those who chose to believe in alt-reality swelled. “Take the red pill” and you will understand that jet fuel can’t melt steel beams, or that all the Jews were secretly told not to go the World Trade Center that day, or, to quote the man who would go on to become America’s most infamous reality rejecter, that Muslims in New Jersey were cheering as the towers fell. It was our first taste of how much ugliness lay beneath the devotion to these quasi-principles: You were most likely to reject reality if reality had somehow rejected you; you were most likely to suspect entire groups of people of being puppet masters if you hated or feared those groups in the first place. It was no great leap from there to “Soros controls everything.”

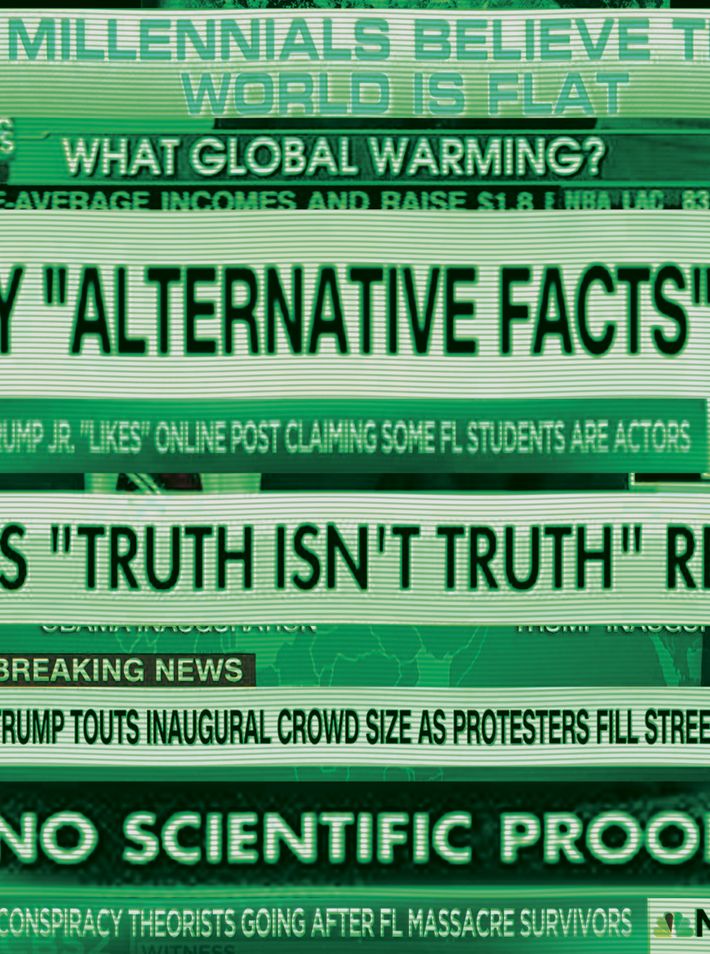

Today, The Matrix is less a touchstone than something that’s now so deeply threaded into the way we think and talk that it can sometimes feel invisible. Its loudest manifestations are also its most malignant: The clown-in-hell mad-prophet fulminations of Alex Jones’s InfoWars, Pizzagate, QAnon, and the anti-Semitic mutterings about “lizard people” of which Alice Walker is so enamored all retail, for the most morally depraved reasons, the idea that “reality” is just a pane of glass concealing the truth and that the only way to reach that is to pick up a rock and throw it. Some of the manifestations are mere eye rolls, like the recent mini-trend of professional athletes who are flat-earthers, whose circular logic combines “If I can’t see it, I can’t believe it” with “Why can’t you see it?” Some of them are just linguistic: Headlines like “Here’s a Better Way to Peel Garlic” became “You’ve Been Peeling Garlic Wrong Your Whole Life” because in the post-Matrix universe, “You have been living inside a delusion, you big dimwit” is an actual selling point.

The Matrix is in every single “Everything You Know About [X] Is Wrong” story. It’s in the phrase “life hack,” which suggests that your daily existence is a code you need help cracking. It is, in often pleasurable form, in the first half-hour of The Rachel Maddow Show, during which she basically says to viewers, “I’m going to tell you something you don’t know about and can’t connect the dots on, but submit to knowing you understand nothing, and by about 9:25 I’ll make it make sense to you and you will join the ranks of believers.” It’s in a certain segment of the hard left that insists corporations are controlling you in ways that you’re too complacent to understand (because you took the blue pill, you ignorant dope). It’s in the fetishization of counterintuitivity that has spawned its own prophets, worshippers at the altar of Malcolm Gladwell. It is in the voguish Trump-era fun of talking about the “darkest timeline.” It’s in those we’re-living-in-a-broken-simulation conversations, but even more deeply, it’s in the slightly glassy look your weirdest friend gives you when you try to change the subject and he says, “No, but we really are.”

Unlike Star Wars or Harry Potter or any number of other beloved franchises, The Matrix inspires relatively little devotion to its actual content. There’s not a lot of talk about Neo or Morpheus or Trinity or the Oracle as characters, nor is there much inclination to speculate about what happens next. To be sure, nothing can cut the legs out from under a franchise like two solemn sequels handed down like stone tablets in the same year, and in the Department of You Get What You Give, it’s worth noting that warmth, emotional resonance, and a sense of humor, which can often increase a property’s durability, are not exactly The Matrix’s thing. It was not an adventure or a lark but a manifesto. Its adherents mined it for ideology and info, then discarded the husk. And what they took from the movie — what makes The Matrix’s long tail so long and so unusual — was a negative. The Matrix did not offer its disciples the joy of discovering a new reality but rather the empowerment of nullification — of casting off whatever temporal, physical, practical, or apparent reality doesn’t suit you. The film gives everyone the authority to say This isn’t happening. But all it has to offer in response is a pronouncement that, as cold comfort goes, could have been drawn directly from The Sopranos (which also had its 20th anniversary last month): One thing you can never say: That you haven’t been told.

*This article appears in the February 4, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

More From This Series

- The Beatific Imperfection of Keanu Reeves in The Matrix

- How The Matrix Got Made

- The Matrix Taught Superheroes to Fly