There are theoretically a whole lot of people whom Dan Gilroy stands to piss off with Velvet Buzzsaw, his art-world horror-satire, which debuts today on Netflix. It’s an outsize takedown of the speculative, hype-fueled market, which happened to premiere at the Sundance Film Festival this past week, a speculative, hype-filled market in its own right. And its premise — that people who seek to profit off creative works (and in the case of Velvet Buzzsaw’s posthumous outsider, personal tragedy) deserve to die bloody deaths, is certainly a provocative one to throw out in Park City between $15 million Amazon paychecks.

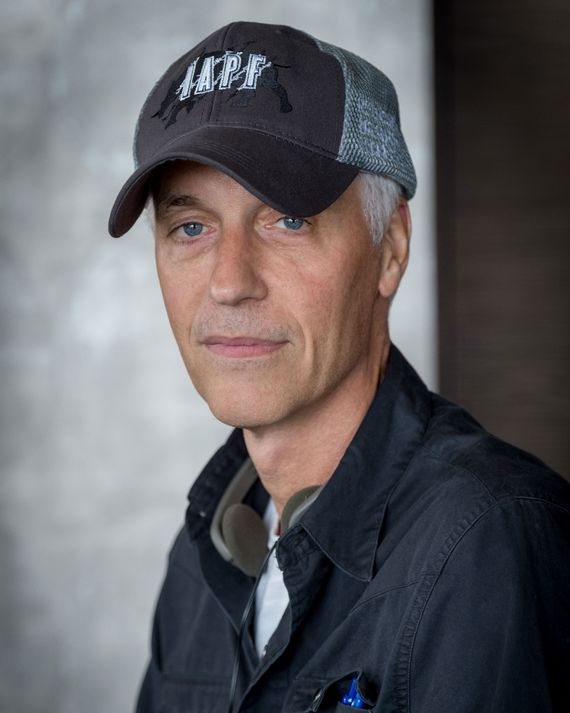

But the film, which stars Jake Gyllenhaal as a critic whose influence comes back to bite him — and an entire network of conniving art-world figures — seems just as likely to be immortalized as a modern cult classic, particularly Gyllenhaal’s already memeified performance. “Camp and kitsch became our friend,” Gilroy told me when I spoke to him on the phone this week. Gilroy and Gyllenhaal previously worked together on 2014’s Nightcrawler, which was set within the “if it bleeds, it leads” underbelly of Los Angeles local news, and now they’ve created another unforgettably deranged character in Morf Vandewalt, to complement the equally deranged world Gilroy is sending up.

But if Gilroy and Gyllenhaal are leaning even more into the camp of it all this time around, it’s all ultimately in service of the eternal questions that haunt artists of any medium, not least of all film — what art is worth, who decides what it’s worth, and who gets to see it. I spoke to Gilroy about the markets of Art Basel and Sundance, honing his art-speak, and just how loud Toni Collette can scream.

Vulture: In Velvet Buzzsaw, you’re critiquing this idea of an art market and the valuation of creative, intellectual ideas. Art Basel is one particularly exaggerated version of a place where that happens, but Sundance — where the film premiered — totally is another one. Did you have any preconceived notions about how this film was going to go over in that environment?

Dan Gilroy: I thought Sundance was the perfect place for us because Sundance is a place that celebrates artists and encourages us to try new things and explore, which is very much what we’re doing in this film.

Now, in terms of how the contemporary art world is gonna look at us? I have no idea. When I did Nightcrawler — and we skewered, you know, the world of local television news — afterward everybody’s coming out saying, “Oh my God, I love the movie.” And I’m thinking, We just took your world and kinda threw a Molotov cocktail onto it. But the local-news people all loved it. They let us shoot in their studios. And I was thinking, Have you read the script? Do you understand what we’re doing? But it seems like people aren’t turned off by satirizing the world that they work in, so maybe the contemporary art world will like us, too. I hope.

One of the elements of the film that I can imagine was fun, certainly in the writing process, was the “art-speak” — the very obtuse, heady way in which critics and gallerists and artists create meaning around their work. Did you work with anybody while writing those parts of the script, or did you just immerse yourself in that language and read a bunch of Art in America?

Yeah, I researched it for months, read articles, interviews; I brought in three technical advisers. And it is its own world, and it is its own sort of language. And I thought I had the language down at times, and then somebody who runs a gallery in L.A. would come in and say, “You should change that word to this, because that’s not a word we use.” And it is its own lexicon. There’s no question about it. But I like going into a world and learning the language of it.

The language is like a costume for the characters, this thing that props them up before their fall. In my review I was trying to put my finger on something about it … it’s sort of hard when you’re writing a review in two hours right after seeing movie, but …

Oh my God.

Yeah. But —

I would say I liked your review or didn’t, but honestly I don’t read reviews, so whatever you wrote —

Oh, that’s a whole other thing to unpack.

Yeah.

Well, I wrote that there was something about it that felt like medieval street theater. Plays for commoners being put on in the square where the noble people get killed in violent form just for the entertainment of the people.

… The Fyre Festival.

Exactly, yeah. I mean it feels like between this and the Fyre Festival and then whatever is going on on any given day in politics, there is this appetite for a very base kind of Schadenfreude or catharsis, a revenge on the powers that be through art.

You know, it’s funny. When you do a thriller and people are getting killed, you have to decide early on: Are they innocent people being killed and you feel bad for them? Or are they people who deserve to die? And I remember, for a week of back-and-forth, I thought, Are they being terrorized, and they’re good people? I really explored that, and eventually decided, No, no, no. They deserve to die. And then I thought, Okay, this is gonna be funny. So I really started to lean into the satire of it. Camp and kitsch became our friend. Very much so.

And it was very much appreciated on this end of things. So then, I guess that raises the question: In all the research you were doing and people you were consulting about this, is anyone going to be upset about seeing their proxies getting violently dismembered onscreen?

I can tell you I was very heartened last week when I watched a really great documentary on HBO called The Price of Everything. Which is about the contemporary art world, and in which the filmmaker took, I think, a year and interviewed all the titans of the industry across a broad range. And they’re all talking about all the same things that we’re talking about, and people doing the same things. So I think we’re pretty accurate about what people are doing. I don’t know if anybody in particular is gonna see themselves, but certainly there are economic discussions and shenanigans, and I think people will certainly go like, “Oh, yeah, that’s going on.”

Did you have a favorite death scene to direct?

I think my favorite one to direct was Toni Collette. Because when she screamed, she screamed so loud that no matter how loud you yelled “cut,” she couldn’t hear. So we would be 20 feet so that she could stop, but she’s so piercing and loud, because she was so into the scene, that we’d have to actually physically go over and tell her she could stop.

Was she cast before Hereditary? Because since then I feel like the world finally knows that she’s got the best face for horror in the world.

Hereditary came out right when we were casting. She was already on our list. She was definitely somebody we were going to, but Hereditary was out and was obviously great for her.

You clearly have an eye and a taste for the sort of cravenness and darkness within certain Los Angeles scenes. But what made you specifically want to set Velvet Buzzsaw within the L.A. art world, as opposed to any other art world?

Well, for one, the L.A. art world is a thriving contemporary art market right now. It’s a lot of energy; a lot of people are really intrigued with what’s going on in L.A. so that was good. And the other is just that I think L.A. is a place that you can tell an endless amount of stories, and it’s got a wild energy to it. It’s sort of uncivilized and unformed, and it feels like the earth could just, at any moment, decide it doesn’t want it to be here anymore and it could go away. Which is odd because, like, in New York City and Chicago and other cities, you feel like nothing could ever destroy them. They’re always gonna be there. They’re permanent. We’re like little ants running around in them. Out here, there’s just a weird, electric energy, which felt really good for this film.

You and Jake Gyllenhaal now have these two really unique collaborations and characters you’ve made together. Did you write the part of Morf for him from the beginning?

I did. I wrote this specifically for Jake. I did. And I wrote Renee’s part for Renee.

Cool. So how much of that embodiment — the physical details, the body language — was just Jake? What was on the page? What did you build together?

I gave him the script and he created everything else about the character: the look, mannerisms, how he walks, how he talks, where he lives, what kind of car he drives. We picked the Mini Cooper Clubman. He wanted that. He has a flip phone; he wanted a flip phone.

Oh, right, I remember that. That was such a choice.

He decided, one day — “I use a flip phone.” And I go, “Really? Why?” And he goes, “I like tradition, and my character’s a traditionalist.” And I said, “Okay!” So he’s always — you know on Nightcrawler, he was the one who said, “I’m going to lose 30 pounds, and I wear a scrunchie on my hand, and I put my hair up in a man bun.” He comes up with these things, and it’s wonderful because he’s taking ownership of the character, which is so important, right?

You did your research for the whole milieu of the film, do you know what his relationship is to it? Because now he’s done two movies set within the L.A. art world that are pretty critical of it. I’m just so curious!

No, and I know he lives in New York, and I think he rubs shoulders and elbows with quite a few people in the contemporary art world through some of them. I know he likes contemporary art. I know he goes to galleries quite a bit, and he certainly appreciates it, but, no, I don’t think there’s any in particular that would explain it.

So, as we’re talking, the film is out tomorrow on Netflix. On top of the perversity of the film itself and getting to critique the whole creative economy, releasing on Netflix also feels like a whole other meta-layer of that discussion.

You know what the real layer of Netflix is? Netflix is the only one right now that’s putting the money out, that I know of, on a regular basis to people making slightly unorthodox things. I mean, look at Roma. Who’s going to put the money up to make a black-and-white film in Spanish? Who is going to put the money up to make a mixed-genre film like Velvet Buzzsaw? And to be honest, Netflix is front and center, and that’s really what it boils down to. I understand from a lot of criticism that it’s a monolithic company with mathematical equations to decide what people wanna watch, but that’s the delivery-platform side. But for people who are making things, Netflix is just like an oasis.