It all begins with a strange apartment. A newly separated woman with a small child are doing their best to start anew. The flat is a reconfigured office space on the fourth floor of a commercial building in Tokyo, flooded from all four sides with radiant light. At night, emptied of commercial tenants, the building belongs only to the unnamed narrator and her 3-year-old daughter. The after-hours are when isolation and darkness creep in. Having left home at a young age for the man she is now trying to divorce, this single mother is, in Japan’s pejorative cultural shorthand, “on her own.”

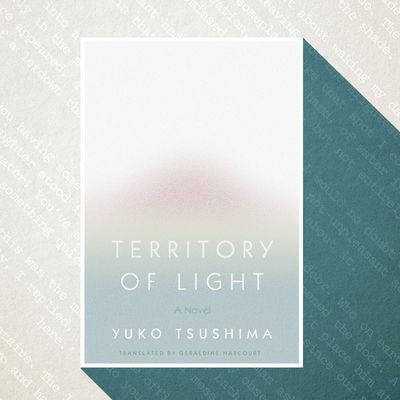

These living quarters are the emotional center of Yuko Tsushima’s Territory of Light, originally published as a dozen serialized essays in a literary magazine between 1978 and 1979. This month, Farrar, Straus & Giroux is releasing it as a slim novel, presumably in hopes of renewing interest in the acclaimed Japanese author, who died in 2016.

Territory of Light is Tsushima’s first posthumous publication in the U.S. Tsushima is clearly positioned to benefit from a general revival of “lost” women’s work, which encompasses recent posthumous publications of Lucia Berlin, Kathleen Collins, Clarice Lispector and Sylvia Plath, as well as a multiyear Eve Babitz revival ending in last year’s biography. Of course, it’s the inimitability of each woman’s voice, and the uniqueness of her experience, that makes her worth rereading. Tsushima is no exception.

Born Satoko Tsushima in 1947, she adopted the pen name of Yuko in part because the Japanese character meant happiness. It was a concept with which Tsushima had a complicated relationship — at least as an author and probably as a person, too. “I have never written about happy women,” she told the Chicago Tribune in 1989. Adversity, she felt, had its upside: “People can become rich by unhappiness. Unhappy people are given a chance to discover true human nature.” Happy people, on the other hand, could “lose sensitivity, and as a result they become poor in terms of human qualities.” Her stories don’t have much use for the second type.

Tsushima’s father, Osamu Dazai, was an unhappy man — an esteemed and deeply insightful author, one of the most prominent fiction writers of prewar Japan — and ultimately, darkness overtook him. He committed suicide with his lover when Yuko was 1 year old. Tsushima published her first collection of short stories, Carnival, at 24, which drew media attention in light of her family legacy.

Osamu Dazai and Tsushima both wrote “I-fiction,” a type of Japanese first-person confessional literature in which fictional incidents correspond to moments in the author’s life, though not completely. The I-novel appeared just after the turn of the 20th century and remains powerful in Japanese literature today. (You might say it was an early form of autofiction).

Like the struggling narrator in Territory of Light, Tsushima had also been a divorced mother on her own in Tokyo. Though she is never exactly her characters, this aspect of Tsushima’s life recurs in other of her I-novels — for example in the young woman who decides against her parents’ wishes to have a baby on her own in Woman Running in the Mountains (1980), or in the 36-year-old divorced mother in Child of Fortune (1978), who is just getting by as a piano teacher when she finds herself alone and pregnant.

What Tsushima and her early women characters undisputedly shared was their milieu. There was a spike in divorce rates in the late ’70s and early ’80s, which some attributed to second-wave feminism. But Japan at the time remained highly patriarchal; divorce was blasphemy (for women) and the care of children deemed to be a woman’s highest priority. Territory of Light broke taboos back then, but it feels in many ways like it could have been written today — both in Japan, where a recent New York Times piece revealed a still severely unequal division of domestic labor, and here in the U.S. Modern women everywhere are no strangers to the same everyday inequalities, big and small, that afflict the mother in Territory.

Later in her career, Tsushima’s work would broaden in style and subject matter. Formally, she was increasingly influenced by the storytelling of indigenous groups like Japan’s Ainu and Australia’s Aborigines. Topically, she took on the ravages of postwar Japan; the plight of children born to American soldiers and Japanese women; the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake. But it’s her work on single women that Americans know — the rest remains unavailable to Anglophones. Out of the 35 novels Tsushima has published in Japan, only 4 have been translated into English.

Night falls fast for the narrator of Territory in the early months of her single motherhood. She drinks; she loses patience with her daughter and sometimes neglects her; she has a humiliating one-night stand; she consistently oversleeps after being kept up all night by her daughter’s crying; and she is always late to her job in the library of a radio station.

“It was my own lack of sleep that worried me,” says the narrator. “I took to downing whisky before bed — more than my limit, in an attempt to stop myself being woken. But no matter how deeply under I might be, I would always hear my daughter’s wails.” The narrator briefly fantasizes about smothering her daughter to stop her cries. In the morning, she wakes surprised that she is still alive. As she rushes off to day care, she is overwhelmed by guilt. “Maybe some part of me wished my daughter dead,” she thinks. “Why would I have dreamed of her dead body otherwise?”

Even today, such sleep-deprived agonies strike us with the power of primal thoughts rarely voiced. They pierce the heart of the Western slogan in vogue even then: that women can have it all. The narrator finds it nearly impossible to hold on to anything, much less everything, and no one is around even to suggest otherwise..

‚ÄúBelieve me,‚Äù a former professor of her husband‚Äôs tell her. ‚ÄúNothing goes right for a woman on her own.‚Äù With that phrase, he invokes the divorce panic of the time ‚Äî the fear that single women would become a moral epidemic, the victims being their children. The narrator internalizes this panic. All around her, there are portents, like the sight of a disheveled old woman (‚Äúshe was probably on her own‚Äù), the floral scent of death emanating from multiple funeral processions, the story of a child‚Äôs¬Ýaccidental death, and news of a fire set by the child of another woman ‚Äî also, of course, ‚Äúon her own.‚Äù These signs echo the message that being alone is a tragedy that can beget still more tragedy.

There is no cultural recipe for happiness to be found in the narrator’s situation. So Tsushima had to create one. Her characters were women on the outskirts of society, but unlike, say, Lucia Berlin, a contemporary who wrote about similar types but tended to end on bleak, Carver-esque notes, Tsushima gently allowed them to find their own sort of happiness. What ultimately made her unique among her feminist peers was an unwillingness to punish her women.

In Territory, this liberation from consequences plays out over and over. In one early chapter, as the mother and daughter are adjusting to life as a duo, they go to a wooded park. The narrator loses patience with her daughter‚Äôs misbehavior, scolds her, and gives her a slap, telling her to ‚Äúget lost.‚Äù Later, as she frantically searches the park for her 3-year-old, she wonders, ‚ÄúWas I going to be taught a lesson for saying those things and slapping her?‚Äù In fact, no: She finds her daughter in a lovely patch of¬Ýlight, standing under a weeping willow.

In the next chapter, the narrator steals away to a bar while her daughter is asleep and gets terrifically drunk with the regulars. For all the foreboding — any other author would be tempted to at least feint at something tragic involving the girl — she remains under Tsushima’s protection, safely sleeping in her room the entire time.

The mother comes very close to being what we’d call today an “unlikable woman.” But Tsushima doesn’t care, because she likes this mother who is slightly askew. She grants her well-being, instead of the misery she seems to be courting. Perhaps Tsushima didn’t punish her characters because she felt they were punished enough by society.

Or perhaps Tsushima didn’t punish her characters because she would have been punishing herself. From the suicide of her father to the 1985 accidental death of her small son, Tsushima learned more than once that the world will do its worst, no matter how you feel about your own culpability. There’s no sense, she seemed to say through her fiction, in blaming yourself for all the ugly things life brings along, which society does nothing — at best — to prevent. As individuals alone in that society, people “on our own,” all we can do is try to make things better, greener, brighter.

At the end of Territory of Light, the narrator packs up and leaves her bright, empty office apartment, moving into a cramped, dark space nearby. While she gives no specific reason for the move, it may be an act of liberation; her husband has finally signed the divorce papers. She is uneasy staying on in a building that he helped her choose and which, coincidentally, bears his name. Leaving is a way for her to sever ties completely with him and her old life. It is the logical choice of a woman who has few options of any kind. Yet there is hope in it, simply because she has more agency than she did when we first met her. She is learning, at last, to be on her own.