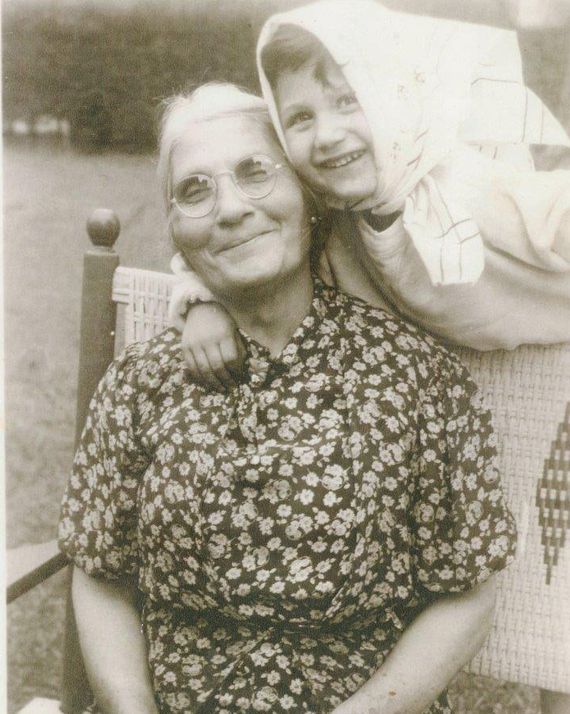

Frederic Tuten, the novelist whose memoir My Young Life comes out this week, grew up in the leafy, and at the time very Jewish, neighborhood of Pelham Parkway in the Bronx in the 1940s and ’50s. He shared a one-bedroom, ground floor apartment with his Sicilian grandmother Francesca, his first-generation American mother Madelyn, and every now and again his father Rex, a good-looking Southern man who also had another family in New Jersey. It was the kind of building where the hallways were permeated with the aroma of onions sautéing in schmaltz — a marked olfactory contrast to the meatballs with parsley and pine nuts Francesca would make and that he would, like everything old-country that she cooked, despise.

Tuten’s mother thought it a wise idea to live in a Jewish neighborhood where the kids were more ambitious. Maybe it would rub off, as that father of his was certainly no role model. He could get a good education and make something of himself, maybe a lawyer or a doctor, make his mother proud, maybe show his father up, and live the postwar American dream.

My Young Life, which I acquired when I was an editor at Simon & Schuster, is a love song to a lost New York. Tuten and I grew up in the same neighborhood, though 25 years apart. Time, however, stands still when you’re from the Bronx. You’re always farther away from the achingly hip scenes in “the city,” as we called Manhattan, than anyone — and it’s not just the miles, it’s the psychic distance that enforces how long and hard of a journey it will be to get where you belong.

Tuten captures the emotional essence of the struggle to not only transcend geography but also class and the limitations imposed by old-world values. The struggle to both leave home, where you are loved unconditionally, and maintain ties to it when you finally get the hell out is beautifully told by this dutiful son whose commitment to family wanes as he gets closer to the place where he feels unconditionally accepted for his desire to become an artist — not exactly the thing one’s first-generation family sees on the list of career possibilities for their children.

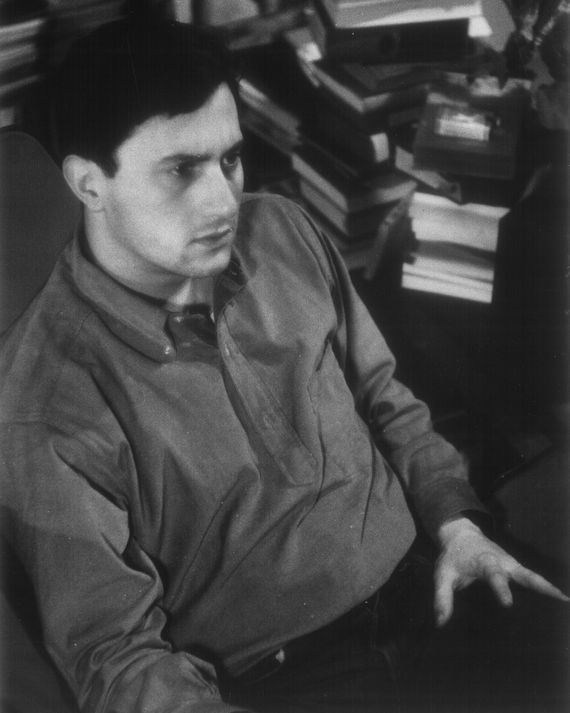

Tuten went his own way at an early age, announcing that he wanted to learn to paint and drop out of Christopher Columbus High School. He had dreams of moving to France one day where he would sell his paintings on the streets — this was long before the pedigree of an MFA program factored into such matters.

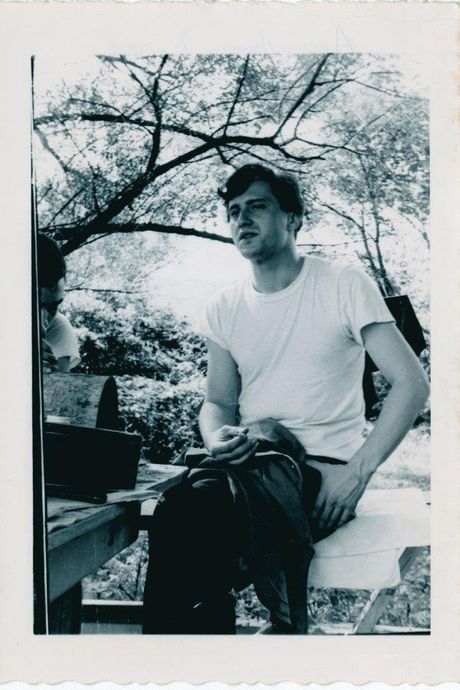

But first he had to make it to Manhattan — he was sixteen, and his eyes already wide, his emerging practice as an artist opened to new possibilities, and it’s here that we begin to see the makings of the artist and writer we know today — inquisitive, respectful, adventurous, and often horny. His trips to “the city” would land Tuten in bed with hot waitresses at the burgeoning MacDougal Street café scene. We learn from him that the sex is better downtown, especially for young artists and writers who are catnip for hipster chicks. Real post-Bronx life began, as it did for so many of us, with those trips downtown.

As it turns out it was writing, not painting, that became the art form that established his presence, but if you follow him on Instagram @frederictuten you’ll see that he has returned to his first love and is now on the roster of Planthouse Gallery.

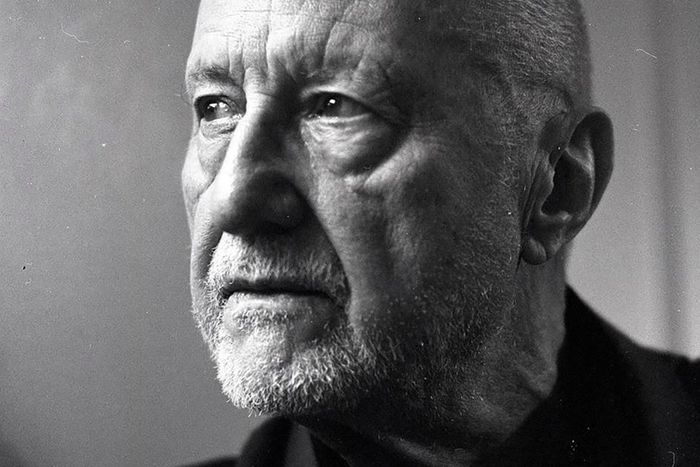

Tuten, a fetching octogenarian, who was Diane Keaton’s boyfriend for a while, became one of those writers who attract famous fans who become famous friends. There’s Steve Martin, who will do a Q&A with him at the Paula Cooper Gallery on March 11. The late great painter and intimate friend Roy Lichtenstein did a few book jackets for him and was also his East End landlord. And there are more art-world types in his crowd, like the long-married painters Eric Fischl and April Gornik, and curator and historian Hans-Ulrich Obrist.

Tuten has also acted in an Alan Resnais film; is a darling of avant-garde journals like BOMB, Fence, and Conjunctions; and had his first novel, The Adventures of Mao on the Long March, reissued by the ne plus ultra independent literary house New Directions.

He is also a revered writing teacher — he eventually finished high school; went to CCNY, then known as the Jewish Harvard; went on to get an MA/PhD at NYU, setting him up to go back to CCNY to teach writing to, among others, Walter Mosley and Oscar Hijuelos.

I have always seen him as an elder statesman of the 20th-century American avant-garde and as a landsman, in the truest sense of the word, given our Pelham Parkway birthright and the shared story of finding our way downtown at an early age and making a life in the arts — precisely the opposite of what our first-generation parents imagined for us.

In almost every decade there has been some scene or other that drew us, we of the boroughs, we who cross bridges and go through tunnels to find ourselves. For Tuten it began at the galleries in the ’50s; for me it began at the clubs in the late ’70s; for others it was vogueing at Harlem’s 1980s ball scene or, perhaps, slam night at the Nuyorican in the ’90s — so many different and vibrant and often transgressive subcultures. There was so much experimentation to do when you went downtown from the Bronx.

While Tuten still lives in a walk-up in the East Village, as I do in the West Village, we both realize how lucky we were to get downtown when we did. Young people from the Bronx, hoping to break into some alternative scene or other, hoping to find a community of like-minded people, hoping to flex a little artistic muscle with people of similar interests and ambition, simply can’t do that in Manhattan anymore. Brooklyn, although now as expensive as Manhattan, has become the place to be.

Or is it? Signs are showing that the Bronx — like Brooklyn, now gentrified all the way to Nostrand Avenue — may be the hot new place. When Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez took her seat in the House, it heralded the Bronx’s return as the launching pad for the children of immigrants to take off from and brought out a kind of Bronx pride in many of us that we hadn’t felt in years.

Mott Haven in the south Bronx is being revitalized and getting ink. And the Bronx Museum of the Arts— in the southwest Bronx near Yankee Stadium, is presenting important exhibitions reflecting the borough’s diversity. Art-world hipsters have staged “underground” pop-up events in parts of the south Bronx that they would never have considered five years ago.

Once the Bronx was burning, but now it is smoking, as the heroin dealers used to say. Perhaps it’s time for Tuten to head back up there with me and take in the latest food scene, Albanian, according to the New York Times, in our old neighborhood. We can regale in our escapes and maybe even wonder about trading our downtown walk-ups for elevator buildings on the wide and gracious parkways of our youth, when all we dreamed about was another life.