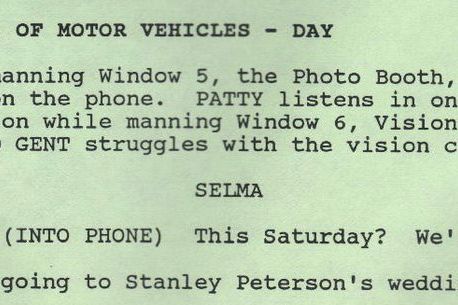

There is no character in the Simpsons universe more mysterious, or more raisinlike, than Hans Moleman. A feeble and nearsighted old man who often meets with an unfortunate end, Moleman has been appearing on the show for nearly 30 years and is easily one of the oddest background characters in the Simpsons’ vast chorus. Moleman first appeared in season two’s “Principal Charming,” where we see him struggling with the eye chart at the DMV while Patty and Selma Bouvier discuss their weekend plans before revoking his license. It’s the first piece of bad luck of the many that would follow.

Speaking to Vulture, longtime Simpsons showrunner and executive producer Al Jean spoke fondly of Moleman and reflected on how the character came to be and how it nearly didn’t. It turns out that Moleman’s peculiar appearance nearly got him axed right away.

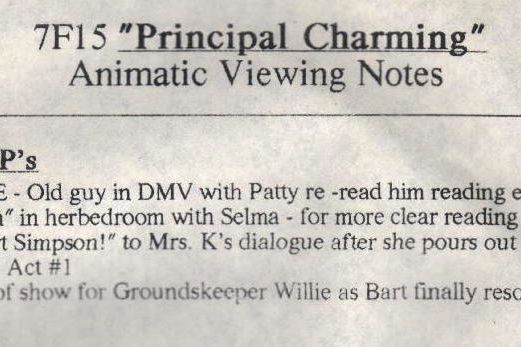

According to Jean, The Simpsons has an internal rule set by the show’s creator Matt Groening that background characters shouldn’t look more unusual than main characters, and the odd-looking Moleman stuck out like a withered thumb. “It really stood out as being kind of not a Simpsons regular design, almost like a mole, though in human form,” says Jean, who notes that Moleman was “a little contrived and a little weird” and didn’t look like a typical Simpsons human should. “At the color screening, Matt Groening stood up and said, ‘This should never appear on the show again,’” Jean recalls. So naturally, the writers decided to keep bringing him back. These days, Jean says, Groening “loves him as much as anybody.”

In that first appearance, Moleman is referred to in the script simply as “KINDLY OLD GENT,” and an internal Simpsons memo from the time refers to him derisively as the “potato-looking man.”

On the DVD commentary track for “Principal Charming,” the episode’s director, Mark Kirkland, recalls that Moleman was initially “quite controversial in the writers room,” to which Matt Groening replies, “Well, we didn’t expect him to come back looking like a shriveled potato.”

After deciding to keep him around, the writers dubbed him “Moleman” for his blindness and wrinkled, molelike features. Since “Moleman” sounded vaguely German, the antiquated first name “Hans” was tacked on to the front, and Hans Moleman as we know him today was born. It was a rough and fitting start.

The Simpsons often rewards obsessives with meticulous sight gags that may only be onscreen for a single frame, and if you freeze the shot of his license in that first appearance, you’ll see that originally Hans Moleman wasn’t called Hans Moleman at all, but “Ralph Melish,” a reference to a Monty Python sketch about a boring man to whom nothing exciting ever happens. The license also states that he is 71 years old, but if you squint hard enough, nothing about Hans Moleman adds up. He’s a slow-moving contradiction.

In the season-four episode “Duffless,” Hans makes the startling claim at an AA meeting that alcohol has ruined his life and that he’s actually only 31 years old. Meanwhile, while his license identifies him as a professional driver and he’s often seen driving commercial trucks, he never does so with anything approaching competence.

So what does he do? Here’s where the plot thickens like Moleman-brand gruel: It’s established that Hans is the former mayor of Springfield, but he is seen working a variety of wildly different jobs, including hot-dog vendor, prison librarian, early morning radio DJ, and janitor at the nuclear power plant.

Moleman’s complexion has fluctuated inexplicably between yellow and brown, and Homer has described kissing his head as “like kissing a peanut.” Deepening the mystery, the seemingly meek Moleman “has been described as a great lover,” according to Jean, and his biography, which bears a photo of him sitting on a motorcycle, is titled Magnificent Bastard: The Life and Loves of Hans Moleman.

On Twitter, former Simpsons showrunner Josh Weinstein once shared an unused script in which Moleman leads a double life as an action hero in the mold of James Bond and has a twin brother named Etienne, and his alter egos get even more surreal. According to Jean, the similarly named Fantastic Four villain “Mole Man” was an influence, and when Homer falls into a subterranean cavern in the season-11 episode “Hello Gutter, Hello Fadder,” he finds Moleman operating an earthquake machine and lording over “the fortress of the moles.”

“So it is possible that he’s king of this underground realm,” says Jean.

Indeed, pull back the wrinkles and Moleman contains multitudes. He has the deflated cadence of Droopy Dog and the small stature and calamitous blindness of Mr. Magoo, though whereas those characters invariably triumphed against the odds, Moleman is invariably crushed by them.

The Simpsons likes to use Moleman in specific ways. He’s often used as a scene-buttoner or to aid a transition by providing a quick background gag, usually at his own expense. In fact, the most consistent running Moleman gag is how often and how violently he dies. Moleman has been killed many times over the course of The Simpsons (a fan site puts the number at 26) and in a flamboyant variety of ways. His first death came in the season-four episode “Homer’s Triple Bypass,” in which Moleman can be seen driving a tractor-trailer that’s towing the childhood home of Edgar Allan Poe when an impatient Homer runs his vehicle off the road and it promptly explodes. Since then he has been thrown out of a window, crushed by concrete, burned alive, buried alive, eaten by alligators, executed by the state, suffocated by a giant bubble, had his brain drilled by Mr. Burns, and been blown up many, many times, among other things. That’s in addition to being harassed by the mob, getting knocked out with a book by Homer, and, perhaps most famously, being hit in the groin by a football in his own movie. In a way, Moleman is the precursor to South Park’s Kenny, except when Kenny dies, the other characters notice and are outraged. When Moleman dies, no one notices or cares.

Even when Moleman doesn’t die, he’s the comedy equivalent of an ellipsis. He rarely affects the plot. (Jean says he “rarely gets more than two lines and a crack.”) His scenes end with him being dropped off at the wrong house by Selma after a bad date or left radiating in the X-ray machine by an absentminded Dr. Hibbert. He is ignored, forgotten, and overlooked. He is saying “Boo-urns” even if no one is listening.

A production memo from his debut appearance in “Principal Charming” called for Dan Castellaneta to make the voice “less feeble,” which would seem like an odd choice considering how the character’s frailty is a key trait since he is run over constantly, and literally, by an uncaring world.

“I like to use Hans Moleman to illustrate that even the most wonderful events have a downside,” Simpsons writer Tim Long said in an email. For example, if Springfield got a beautiful new shopping mall, Moleman would likely be “trampled by the excited crowd on opening day.” Long went on to explain how he sees Moleman in philosophical terms, calling the character “a symbol of the crushing anomie and loneliness of modern existence — but also of man’s indomitable will to confront those horrors. He’s straight out of Samuel Beckett, a man who can get out of bed in the morning but at the same time recognize his own crushing isolation.”

That’s the pathos of Moleman: the feeble, lonely, myopic old geezer puttering along from one misfortune to the next. You feel it when he berates Apu for briefly closing him in his shop, saying: “You took four minutes of my life away and I want them back! … Oh, I’d only waste them anyway,” or in his morning radio show Moleman in the Morning, which he uses to update his listeners on “the agonizing pain in which I live every day.” He would make you cry if he wasn’t so funny.

Since he was never meant to be a recurring character, Moleman’s very existence is both a running gag and an inside joke, and when Simpsons writers talk about him they do so with obvious fondness. Beyond the warm feeling a person might have for their quirky old uncle who’s surprisingly still around, the writers have total freedom with Moleman. As a character he’s so inconsequential that he’s become an indestructible vessel for throwaway jokes and absurd gags. As Jean puts it, “When his [Groening’s] first comment was, ‘He should never appear again,’ it’s pretty hard to ruin the character.”

While The Simpsons takes place in an elastic reality in which Homer can fall off cliffs and suffer countless head traumas without issue, there are limits. When characters that are well-established in the world and who have relationships to other characters die, it’s a show-altering event (R.I.P. Maude), so they can’t be run off the road by Otto’s school bus and blown to smithereens just for a quick gag. But Moleman can.

“You’re not going to very well have Principal Skinner or Flanders driving that car,” says Jean, “but Moleman’s not a problem.”

In that sense, the question “Who is Hans Moleman?” is unanswerable. Moleman is a tabula rasa, a comedic blank check for any situation. And yet, despite that mutability, Moleman is somehow eternal — the character nobody wanted but who keeps on shuffling back.

“He’s been blessedly free of any change or growth, any learning or any knowledge,” Jean explains. “He’s the same lovable loser stuck in a line.”