Juice WRLD died at 21 of a reported seizure on Sunday, December 8, 2019. This profile was reported in early March 2019.

In a neo-Italianate mansion in Beverly Hills, a group is gathered around the kitchen island waiting for 20-year-old rapper Juice WRLD (birth name Jarad Higgins) to come downstairs. The kitchen is stocked with boxes of Sprinkled Donut Crunch and Honey Bun cereal. Juice’s friend Caesar pads into the kitchen in Gucci slippers to reheat some chicken Parmesan in the toaster. Pete, his manager, says he’s going to play us some songs from Juice WRLD’s sophomore album, Death Race for Love, and then puts on “Barbie Girl” by Aqua instead. Everyone laughs. After the fake-out, he plays us some of the actual new music, starting with new single “Robbery.”

Juice WRLD is coming off the success of last year’s Goodbye & Good Riddance, whose single “Lucid Dreams” led him to become the next star of the genre occasionally known as emo-rap. His music combines several potent strains of teen alienation genres, recalling nothing so much as nu-metal. It’s angry, depressed, and self-conscious, but also hooky and soaring. On “Robbery” he intones gothly, “I woke up in a hearse,” before adding, “One thing my dad told me was never let a woman know you’re insecure.” But it is talking openly about insecurity, depression, and other mental-health issues, as well as being frank about addiction struggles, that has really made Juice a star. On the new album, he reassures us, “I’m 19 and I’m rich … psych, I’m still sad as a bitch.”

Juice WRLD walks in, wearing wire-frame glasses, ripped jeans, and a T-shirt made of two shirts — Britney Spears on the cover of Baby One More Time stitched to Lil Wayne on the cover of Tha Block Is Hot — as apt a summary of Juice WRLD’s vibe as you could come by. Almost every big male rapper in a post-Drake world has a touch of sad boi to him, but Juice WRLD wallows in Morrissey levels of misery. He got big off raw, sad, songs, but he is also wary of being boxed in forever with the trend. On his new album he moves beyond emo-rap, even venturing into upbeat pop. Juice is currently the biggest act on Interscope, and today he is going to the Sunset Strip where the label will be unveiling a billboard for him.

Emo-rap, which appeared and grew in the last few years as a sideways outgrowth of the bedroom minimal trap rap made on SoundCloud, is at a pivotal moment. Its fascination with Byronic sadness, pills, and misogyny feels different scrutiny after the fentanyl-related deaths of rappers Mac Miller and Lil Peep and the murder of rapper/domestic abuser XXXtentacion. Juice grapples with the change in the music, announcing that he doesn’t want to die like his peers. Its fans are also aging, and Juice himself is no longer a teenager either. He is at a crossroads — go full pop-rap and join Post Malone, Migos, and the like, as his label would probably hope he will, or continue on the emo-rap path that logically leads toward horrorcore. Moving outside his established sound on Death Race for Love marks an evolution, but I ask Juice if he worries his fan base will feel betrayed by a slightly happier Juice WRLD.

“I hope not. Because even when I find my true happiness, which I find more and more of it every day, I ain’t finna stop the mission that I’ve been put on. I’m gonna still lead people through whatever they’re going through,” he says. “And since I’ve gone through it. I could forever speak on it, no matter how I feel. I could be happy and make a song for people that’s dealing with depression. I could be sad and make a song that will make people smile and be joyful. As long as you felt those emotions, you can channel them back anytime. You can think back and relate to it anytime. As a part of learning the lesson, you keep that shit instilled in you.” As for the music, “It’s all about progression. Evolution. You can’t be afraid to evolve.”

The group springs into motion when Juice arrives, shuttling him to the large vehicle he’ll be taking to Sunset Boulevard. A crowd is assembling outside the luxury fashion store across the street from the billboard (which is currently covered by a drape). The fans are mostly teens, with multicolored Manic Panic hair and cartoon-character backpacks. Some of them are wearing all black and vaping, others have brought pizza. Everyone looks like a potential Suicide Squad character. Juice’s vehicle pulls up, and the crowd rushes in chanting, “JUICE! JUICE! JUICE!” (I am so comparatively old that this makes me think about the O.J. Simpson car chase), while still politely obeying the security instructions. The van door opens in a cloud of weed smoke. The billboard, depicting Juice WRLD’s past and plausible future platinum records, is unveiled. He answers questions one-on-one from the car so intimately it’s impossible to hear what is being said. Some pass him blunts and vapes to hit, as everyone films and takes photos. A Hollywood tour van passes by on Sunset and gawks at the scene. Juice waves at them and smiles. They all wave back.

Then Juice gets out of his van, stands on top of another luxury car pulled up in front, and starts playing cuts from the album on the stereo. He is emo-rap’s Lloyd Dobler, blasting his lovesick songs to the adoring crowd and the Sunset Strip while rapping along. Suits from Interscope — all older white men — lurk on the sidewalk and look at their phones. Toward the close of the event he leads the small crowd down the end of the block on Sunset and back in a tiny parade. The crowd is respectful and appreciative of their idol in the flesh, and the whole thing wraps up before sundown. It’s a school night.

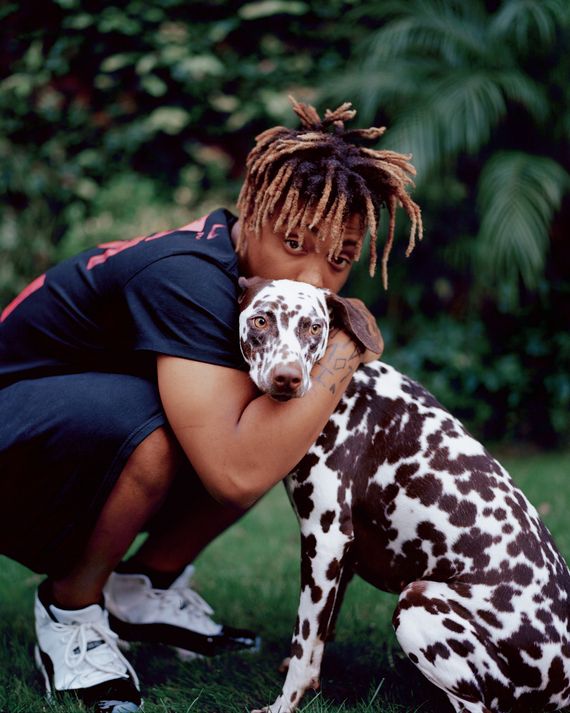

Back at the mansion, Juice is unwinding. Friends come and go through the house, whose surfaces are stacked with leftover Postmates orders and weed paraphernalia. A cute goth girl that is purportedly Juice’s girlfriend comes downstairs periodically with a large dog. It feels much like a frat house, albeit a fancy one. I sit down with him in a low-lit TV room off the kitchen to talk.

I ask him how he thinks today went. “It was my first time doing something like that.” He says, his voice a gravelly whisper. “It was good to interact with the fans more personally. It was cool to have a smaller crowd for once ‘cause I could interact one-on-one with people. I was just, like, randomly responding to people. When you have a big crowd in front of you, you can’t just sit and answer everyone’s questions, tend to everybody’s needs.” I ask if he senses how deeply connected to him fans feel. He nods. “Music, it helps, but sometimes what really helps is just having a good conversation with somebody and kinda helping them talk through whatever demons they’re fighting. And it sucks, I’m really socially awkward. I ain’t used to be, but I am now. And maybe I’m just socially awkward to myself, ‘cause nobody really agrees, but sometimes I just feel socially awkward.” His openness about feeling awkward is, of course, another point of connection for fans. “I’m not the only one going through that. All right? But when you meet somebody else like that, y’all don’t even feel awkward. There’s like a vibe you get when you connect with somebody that’s going through the same shit that you’re going through.”

Talking it out, in his music and real life, is of paramount importance to Juice WRLD. With his platform, he feels a responsibility. “Mental health is something that has been neglected, especially in the black community.” He continues, “Some people don’t believe in mental-health care. And they think the answer is some type of church. Don’t get me wrong, I try to pray to God every day. But people use religion to try to cure mental health; they think it’s not an issue that needs to be handled with medical help. I’m not saying any religion is right [or] any religion is wrong. I got my own beliefs, you know. But I feel like mental health is not taken seriously; like either it’s not taken seriously or it’s wrongly diagnosed.” Then he reveals that he is speaking from experience. “I was diagnosed with attention deficit disorder in fifth grade, and my mom put me on Ritalin, Vyvanse, all of that. And I looked back at it and I’m like, Wow, that was not okay. I’m in fifth grade. What am I doing taking Vyvanse and Ritalin? How is a fifth-grader supposed to act?”

To relax he rides dirt bikes (“in the desert”) and watches anime. He lights up as he lists off “Naruto, Dragon Ball Z, One Piece, Sword Art Online, Akame Ga Kill, and Tokyo Ghoul.” Growing up, his parents played “’80s music — Queen, AC/DC, the Scorpions, the Who.” He cites his own influences as including “Lil Wayne, Master P, Ozzy Osbourne, and Billy Idol.” A hard-rock sound could be in his future as well. “I’ll almost definitely get a band together and see what happens.” I tell him that it’s coincidentally Axl Rose’s birthday, a spiritual leader of the ’80s Sunset Strip rock-music scene that Juice loves. He is taken with this info, and says he wishes he’d known that before he went to the Strip today himself.

Then he confides, “What I found out just really killed the last little kid spirit in me. I found out that the bands … some of the bands don’t be cool with each other, and they really just bandmates. So some of them come in and record at different times. That’s wild. I thought bands were just a unit.” An undercurrent of Juice’s existence is that he feels alone in a crowd, something sudden fame has seemingly only magnified in him. His fans do not know him exactly, but they feel deeply like they do, and everyone he meets in the music industry tacitly desires something from him. As in his lyrics, under all that isolation is someone who seems desperate to connect. So the idea that he is heartbroken realizing that rock bands multitrack recordings is very touching.

Juice WRLD’s desire for collaborators is apparent, and he finds comfort in working with elder statesmen of rap, people who have had big careers spanning several albums. The album Juice made with Future was “life-changing; he’s one of the people I really look up to in this shit.” He expounds, “The fact that him and Thug and all these people fuck with me? Like fucking Pharrell just DM’d me. I don’t mean to sound gross, but yo, my music side nutted. That was wild. Pharrell? Fucking Pharrell. I couldn’t even believe what I was reading.” He admires Pharrell’s longevity, and status as a style icon.

Juice is in a different place emotionally than he was making the first album. “You can hear it in my voice. You can hear my demeanor. Shit is different.” He says he’s constantly recording, “but the only issue is, is that subject matter still going to be relevant? Is that still gonna be the sound? Honestly, I don’t give a fuck. I’m gonna always be myself and talk about what I wanna talk about and sing about what I wanna sing about. But I know part of the issue of making music is having to, like, schedule it, and the music may be out of style by the time you drop it.”

So he wasn’t nervous at all about following up on a hit debut or shouldering the expectations of a record label depending on him to carry a sales quarter? “I don’t want to say I’m nervous about it, but, like, a lot of people been in my ear about ‘this has to top the first album,’ and it’s like, I kind of had to get out of that mind-set. Especially because the way I record, I freestyle everything. If you think too much, you’ll start drawing blanks. You’ll start overthinking it. Second-guessing a freestyle is the worst. When you’re going off the top you’re supposed to just go. Just let the music kind of take over and flow.”

Once he reached the appropriate level of immersion, he let loose. “When I got to that point. I recorded the album in four days. And it was like, after that, then I wasn’t self-conscious about dropping music no more. I wasn’t self-conscious about the album anymore. I don’t like that whole competing with myself thing, trying to top myself. It’s good to have goals and to keep climbing you know, but the music is gonna speak for itself. So just me realizing all those things, it kinda calmed my nerves about the new album. I just know I poured my soul into it. Every song but two or three of them on the new album are all freestyles, all made up in those four days.”

His favorite cut on the album is either love song “She’s the One” or another song of which he says, “Don’t judge the name; the song is called ‘Syphilis’” I ask why and he starts doing it for me (“Cuz bitch I be sicker than syphilis …”). I say that Death Race for Love definitely shows some different sides of him. “Yeah, and that’s what the album should be about. It’s cool to have themes. It’s cool to have structure. But at the same time, you create your own structure. There’s a difference between madness and coordinated madness. You don’t have to follow the rules of any book, as long as you have your own rules and follow them. So I just kind of made up my own structure; it’s tied together because of the way I did it. But it’s still my way.”

Juice has real issues in his life besides girl trouble. When I ask if he misses Chicago he says, “Yeah and no. Yeah because I miss the food; I miss my mom a lot.” I say that living away from home is normal for someone his age, and mention how his place feels collegiate. He responds, “I agree with you, but also I disagree. ‘Cause with college it’s like, you can always come home and be the same person you were. When you’re famous and you have a platform, people are automatically going to love you and hate you, just ‘cause of your name. So you gotta be a little bit more precautious, especially if you’re from the neighborhood, and you have some prior beef with someone. They find out you’re in town, that’s gonna make them hot and thirsty for your blood. So certain things about Chicago I miss, but I know I shouldn’t be back there.”

In one new song he mourns the drug-related recent deaths of several of his peers. He tells me, “Specifically, with substance abuse, somebody that’s never done drugs cannot turn their nose up to somebody that’s addicted.” Those struggling, he maintains, need sympathy rather than judgment. “The way that you help somebody out, reach out to someone, offer them a helping hand, offer them a hug, whatever. The way that you do that is not, I repeat, not, by pointing the finger. Telling them that they’re stupid, they’re fucking up their life, whatever. Telling them they’re a piece of shit for doing what they’re doing. That is not the way at all. The way to lead people is to walk, not even in front of them — side to side, holding their hand emotionally through music or whatever you do. And using that to help people push forward. Not scold and drag people into they own mess.” He has clearly thought about this a lot, as he has become a de facto youth ambassador for some of these issues. He is wise beyond his years, especially when speaking about addiction issues and mental health. “People go through different shit, and instead of pointing and calling them stupid, you just have to hold their hand, let them know that you know how it feels, and that it will get better and that you’re there for support if needed.” As an artist and human being, he’s clearly a sensitive soul. “Yeah, for sure. I ain’t even afraid to admit that shit.”