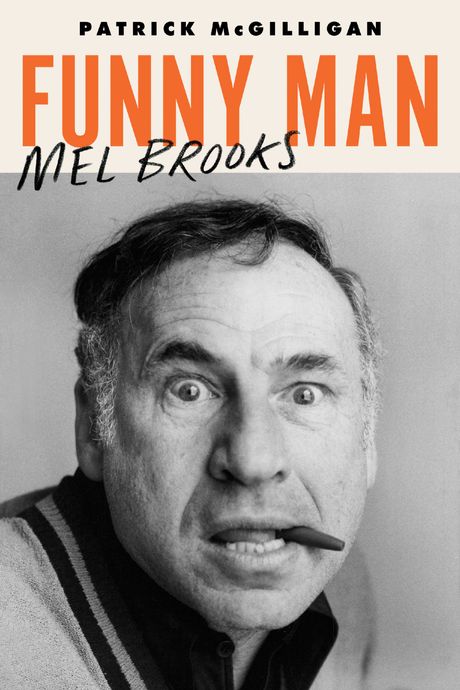

After a career spanning more than 60 years of writing, directing, producing, and acting in movies, TV, and on Broadway, somebody finally wrote the exhaustive biography about the life and career of Mel Brooks.

Patrick McGilligan’s Funny Man: Mel Brooks tells the story of a man who has never stopped hustling in an almost pathological pursuit of the twin needs to entertain and be famous for it. He did with it a very broad, very specific, very careful mix of Vaudeville-honed Jewish comedy, fourth-wall-breaking, and envelope-pushing silliness through his work on Your Show of Shows on ’50s television, progressive stuff like Get Smart and The Producers in the ’60s, and as a titan of screen comedy in the ’70s with Young Frankenstein and Blazing Saddles. Then he topped it all with the much-heralded, record-breaking run of the live musical version of The Producers in the 2000s, turning Brooks into the Broadway baby he’d always wanted to be.

Here are some of the most interesting and rarely (if ever) mentioned tales about Brooks’s tough and unlikely rise to become one of America’s most respected voices in comedy.

1. It took him years to convince Zero Mostel to work with him.

In the early ’60s, Brooks struck up a partnership with TV show packager Stanley Chase, and they shopped The Zero Mostel Show, capitalizing on the success of its star, a formerly blacklisted actor turned toast of Broadway for his role in the 1962 musical A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. (Larry Gelbart, who’d go on to create the TV version of M*A*S*H, worked with Brooks on Caesar’s Hour.) Brooks’s pilot for The Zero Mostel Show posited the actor “as a ‘super-janitor of Greenwich Village apartments, a soulful building manager who dabbles in painting and music while neglecting tenants’ leaky sinks and defective lights.’” Brooks’s pilot script was apparently “precious to a fault, its sincerity and playfulness light-years from his later brand.” None of the networks were interested … and neither was Mostel, and the pilot never filmed. But Brooks “never gave up on Mostel, and time and again in the 1960s he built trust by doing little writing jobs for the actor.” Eventually, Brooks would secure Mostel for The Producers in 1967.

2. He was a one-hit wonder on TV.

With Buck Henry, Brooks created the 1965–1970 spy spoof Get Smart, and he tried to capitalize on its success with a number of other scripted TV projects in the early ’70s … to little avail. With collaborator Gary Belkin, he wrote a very broad, very of-its-time pilot about a “hapless, ‘world-renowned Master Detective’ summoned from Italy by a secret international police agency to stymie the planned assassination of the ‘Shah of Tyrhan.’” The name of that show: Inspector Benjamino. But the spy-parody genre was played out by then, and no network was interested. In 1971, he developed a proposed two-hour special for NBC called The People on the Third Floor about the “tenants of a large apartment building who gather for a house party” that would feature “six or seven vignettes” written by Brooks and other writers. That didn’t go either, and neither did Annie, a 1971 sitcom that made it to the pilot stage. Based on the lives of married comedians Jerry Stiller and Anne Meara, Brooks served as a creative consultant and executive producer, “but ABC, which underwrote the pilot, declined to air the series.”

3. Who knows how he met Anne Bancroft?

After the end of Brooks’s first marriage to dancer Florence Baum, which McGilligan says ended in part because of Brooks’s affair with Eartha Kitt, in 1964 he married Tony- and Oscar-winning actress Anne Bancroft, best known for portraying Annie Sullivan in The Miracle Worker onstage and in film. However, there’s some confusion over how they first met. (Who deserves credit is a recurring theme in Funny Man, and the life of Mel Brooks for that matter.) According to McGilligan, some say they were set up by their teams. “There are William Morris agents who believed it was an ‘agency package,’ because the writer and the actress, both known to be available on the relationship market, were introduced by talent representatives who conspired for the two to meet and shake hands as they walked down agency corridors from opposite directions in late 1960.” Broadway composer Charles Strouse, however, thinks he made the hookup happen. In the late 1950s he had a regular gig “playing piano for musical theater lectures at the Actors Studio,” where Bancroft practiced singing with him as her accompanist. Strouse and Brooks were working on a musical called All American there “when Bancroft stopped by to say hello, and after she departed, Brooks, tongue-tied in her presence, pleaded with Strouse for an introduction.”

4. Blazing Saddles was, initially, a mess.

Films are usually written by one or two people, but Brooks took the well-populated writers room approach — the TV way — for the film that would become Blazing Saddles. Based on Andrew Bergman’s novella Tex X, writers on the project included Bergman, Brooks, Richard Pryor, and Norman Steinberg. The team finished its first draft in July 1972 under the title Black Bart. And it was long — “412 pages say some accounts, or as short as 156.” Among the many, many abandoned elements: “a Catskills-type comedian who opens for Lili Von Shtupp,” the bordello performer played by Madeline Kahn; “a cowpoke named Bogey” that Brooks devised who existed solely to perform a send-up of a sequence from The Caine Mutiny; “a long, rap-style ‘street poem’ Richard Pryor had written for Black Bart”; and a little person character “named Ash Tray, who had an ashtray hat.” Brooks fought long to include that bit, too. “I hated the character and Andy hated the character, but Mel was adamant,” Steinberg says in Funny Man.

5. He didn’t properly credit Gene Wilder’s contributions to Young Frankenstein.

Both Gene Wilder and Mel Brooks were at their best when they worked together. Brooks wrote and directed the original The Producers in 1967, in which Wilder starred as nervous accountant Leopold Bloom. Brooks won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay; Wilder got a Best Supporting Actor nomination. They collaborated again on Blazing Saddles (Brooks made it, Wilder starred in it) and Young Frankenstein (Wilder starred and wrote the script with director Brooks). As for the latter, Brooks marketed the horror parody as a “Mel Brooks Film,” and even included “an eighty-foot-high billboard on the Playboy Building on Sunset Boulevard” boasting that. But Wilder, in addition to having to cede creative control and profit percentage points in his Young Frankenstein contract, could claim it was just as much his movie, having co-written it. The Writers Guild filed a grievance, and “an arbitrator fined the studio ten thousand dollars, the bulk of that sum going to Wilder.” Outside of work, Wilder and Brooks enjoyed “a friendship that endured” until the former died in 2016, but Wilder “never worked with” Brooks again “in any capacity.”

6. His second-to-last film work may never be seen.

Brooks hasn’t helmed a film since the 1995 horror comedy Dracula: Dead and Loving It. Just before that, he worked on another film that’s never surfaced. Les Visiteurs was a massive hit in France in 1993 — Jean Reno starred as a medieval knight who, along with his squire, winds up in modern times, and fish-out-of-water wackiness ensues. Historical setting? Complete and total silliness? That sounds like a movie Mel Brooks, director of The History of the World, Part I and Robin Hood: Men in Tights, would make. The film’s production companies, Gaumont and Canal+, certainly thought so, and they hired Brooks to lead an English-language dub of the film for release in North America, “convinced that enhanced jokey dubbing would boost the U.S. prospects.” So, “for much of 1994, he poured himself into writing and recording” an English dialogue track, only for Les Visiteurs director Jean-Marie Poiré to reject it, as “the film had become a parody, with the knight’s accent so French that it was almost impossible to understand.” Brooks fought back, telling Variety that test screenings of his version did poorly because it had been shown to teenagers instead of his intended audience of “Francophiles.” Miramax shelved Brooks’s version, and two years later, released Les Visiteurs to American art-house theaters with subtitles instead of Brooks’s track. Still, he got paid $500,000 for his efforts.